My childhood was fantastic. I remember it quite vividly. I think I was a good child. In fact, I can recall numerous occasions when family members would affirm this fact. I have two siblings, and I am the youngest, and with that came various perks. Namely, the ability to squeeze through the gaps of discipline that was more thoroughly applied to the older two. This allowed me a more carefree experience. I've never really lost that carefree perspective, despite some of the darker things I have experienced and witnessed between childhood and where I am now, in fatherhood. Overall, when looked at from a very specific viewpoint, my childhood was completely normal and absolutely unworthy of any deeper analysis. However, it is what afforded me this childhood, what was hidden, lurking in the shadows, the architect of my childhood, a privileged and safe childhood of a white middle-class Christian male, that is very much worthy of deeper analysis.

Memories

I went to a wonderful middle-class suburban nursery and primary school. All the teachers were white, mostly women, and all very caring and good at their jobs. They nurtured us and taught us to be good children. The students were good children; they were white children. We were all wonderfully civilized, well-educated, and quite obedient to authority. It goes without saying that all the parents were married, the mother at home, and the father at work. We learned all the things we needed to learn to be good children. Good South African children in the 1980s. We raised the flag in the morning and sang “Die Stem.” I remember our history teacher, an Afrikaans lady, taking great pride in teaching us patriotic songs. We were quite proud when we sang them. We loved our wonderful country.

We played cricket on the field at break time and then went home to our loving mothers waiting at the gate. In the background, occasionally, you would see someone who was not white in a position of service. But you never paid them any attention. They were just there. Close to invisible.

I would go home and watch TV or read books. Every person inhabiting the fictional worlds would be white. And they would be good. And I never ever thought anything other than this was good and as it should be.

On Sunday, we would go to church and be reminded of how to be good, respectful, and to have empathy for others. I never really understood why. It was so frightfully boring for a young child. But I wanted to impress my father. I wanted his love, and even at that age, I knew how important loving God and Jesus was for him.

In the holidays, we would go away to the ocean, as good white families did. This meant long drives to the East Coast for a caravan holiday with my family. Again, the only other families and children there would be other white families and white children. And I never ever thought anything other than this was normal and as it should be.

The only person I knew who was not white was Thebe. He lived on my parents' property. He worked in the garden doing all of the garden work. I was somewhat obsessed with him as a child. I remember following him around, watching him do garden work. He would allow me to help him. Although thinking back, I was more likely a hindrance, but I am certain he would never have said so. At least never within earshot of anyone. And certainly not in English. Nor Afrikaans. Maybe when he was alone with other migrants from Zimbabwe, maybe he would say something in Shona. Maybe, if he was very careful and alone with people he could trust. Maybe.

He had a nephew who would visit. Donald. We would play together in my parents' garden as we were of a similar age. I still remember his smile and his infectious laugh. I also remember knowing, unconsciously, to never talk about our friendship at school. And I never ever thought that this was anything other than right and as it should be.

England

Then in 1989, my family moved to England. I was 8 years old. One of our first class projects that I remember was about apartheid. I was 8 years old. We had to come to class and talk about why apartheid was evil. I had no idea what they were talking about. I didn't know what apartheid was. I'm not sure I knew what evil meant. Yes, we had been told about evil in a snake-in-the-garden kind of way at Sunday school. But I didn't really understand what the English meant by evil. We certainly weren't evil; we were just an average white family from South Africa, obedient and good South Africans. After all, we had Thebe living in our garden, and we treated him well. Like he was a member of our family. I even had a Black friend, Donald. How could we be evil? We went to church every Sunday!

I asked my father for help with the project. He knew everything. He told me the real truth. So that is what I wrote in my project. It did not go down well with the teacher. Nor with all the white English boys who now knew I was an evil and racist South African. I believe at the time, there was a song called “I have never met a nice South African.” Well, up to this point, they still hadn't, I guess.

Time passed, and we became influenced by life in England. South Africa seemed so far away, and as the youngest, the draw of late '80s consumer capitalism was too strong to resist. Breakfast cereals and their plastic toys, endless cartoons, Nintendo, and Toys R Us made a compelling case for the superiority of Anglo-Saxon morality. How could the empty shops and three TV channels of apartheid South Africa compete with all of that?

But then another South African joined our school. As well as the first non-white student. It was only a matter of time before conflict broke out. Sides had to be taken. Conflicted between this seductive new world and hard-coded patriotism, I guess I chose poorly. Choosing the losing team in school fights can be quite detrimental to your social development.

Nonetheless, I learned very important lessons while living in England. The most lasting of these was the realization that nothing could ever be superior to the hard-coded English entitlement to being morally superior to everyone else. I think they may have, in fact, invented morality, like they did with football, tea, and speaking well.

A return

A few years passed, and change was coming to South Africa. My parents made the choice to return. So we returned to a nation riddled with uncertainty. The uncertainty of a country coming to grips with the end of a system that controlled every single facet of life, now trying to define what it was. This mirrored changes in myself.

I had seen a world outside of that world. I was told in absolutely no uncertain terms that we were the bad guys. And to be good meant to be open to other cultures and other points of view. You had to be multi-cultural, I was told, in a school that was profoundly not multi-cultural. This was especially true if those other cultures and points of view were marketable and consumable products to be bought and sold on the open market of capitalism.

Nothing ever stays the same, and time always moves on. The school I had left was in no way the same as the school I returned to.

One example of this was my old history teacher. She took so much pride and passion in telling us the truth of South African history. How we, as White people, had come to be the masters of this land. That it was right and good and God's will that we were there, bringing civilization to an uncivilized world.

Well, she was no longer there. We had a new teacher. Also, we no longer only had to learn Afrikaans and English; we also had a Zulu teacher. I think they were learning on the job, to be honest. It was all very new to everyone.

Oh, and we also now have Black students in our classes. That took some getting used to. In hindsight, I think there were more than a few that never got used to the new reality. Specifically, judging by social media comments made nowadays.

We couldn't at first figure out why they were all so much bigger than us. It was almost as if they were all two or three years older than us. None of us could figure out why that was the case.

Now, instead of just playing cricket on the school field, we played football.

This was in many ways one of the biggest changes! Prior to my time in England, football never existed. The only sports that existed were rugby and cricket. Each is capitalized for its importance.

The Nazis knew what the apartheid government knew. Get them when they are young, and you will have a lifetime of dedicated and unthinking service. What was happening here was the same realization. It was an attempt to get ahead of what was going to come next.

What should have been the end, but wasn't

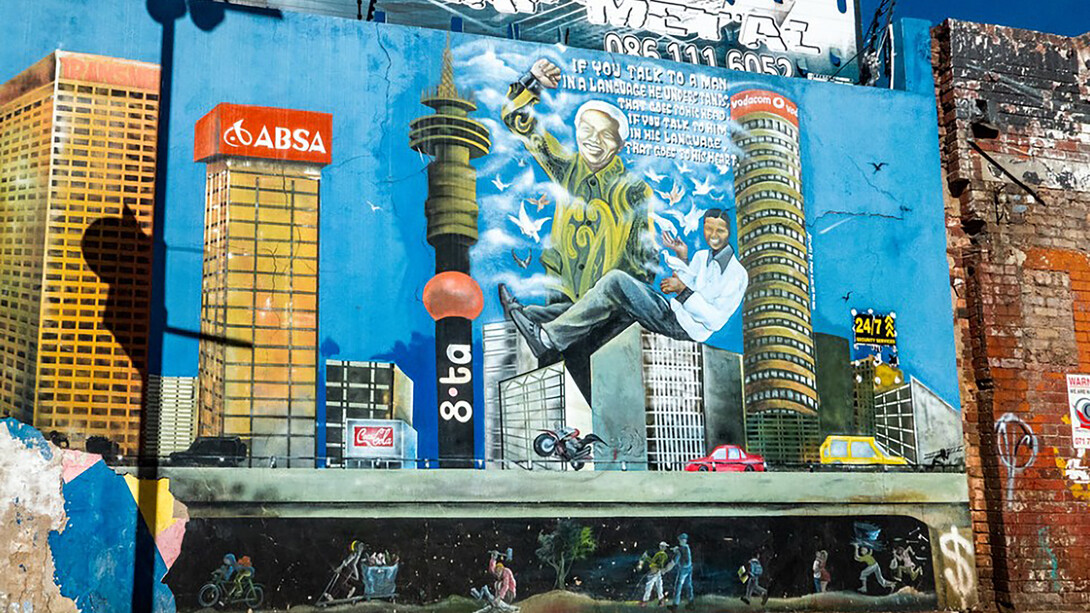

Then, in April 1994, Nelson Mandela became the first Black president of South Africa. Apartheid was over. And we all lived happily ever after.

Just kidding, of course we didn't. What are you, an innocent child who believes in fairy tales? After all, how exactly do you simply deconstruct something like apartheid in three years, from 1991 to 1994? You don't. There's your answer.

In those years after 1994, we whites were at times nervous and even scared. In fact, the word terrified might even be applicable. We knew that there would be consequences. We knew that, because whenever friends and families got together, the worst of what might come next was spoken about. There was no social media in those days, but the spread of fear was just as virulent, as well as the spread of conspiracy and misinformation. Very seldom did anyone raise the idea of how to build better for the future for all. Nope. All that was discussed was the fear of what exactly would be taken away and how violent that taking would be.

TV, no longer controlled, showed more points of view. And many now conflicted with the one point of view many of us were accustomed to. To put it into a larger context, there was a global sense of uncertainty at this time. There were the LA riots in 1992, the assassination of Chris Hani in 1993, and the poll tax riots in England. And of course, the collapse of the USSR in 1991 and the beginning of a unipolar geopolitical reality. The whole world was caught between rampant optimism that the world had turned a corner and the future was finally looking bright, and the fear that beyond the corner, something far more sinister and menacing was lurking. Interestingly, both views were equally accurate.

But then sport happened. In 1995, South Africa won the Rugby World Cup. I remember seeing my father hugging Thebe in the living room of our home, tears streaming down both their faces. For a second there, it looked like we might, in fact, make it out of this alive. For a brief and glorious moment in time, we all thought, This is it; this is how we heal and move on.

University and learning

Jumping forward half a decade, in which not much changed other than the promises of change, I made some very good friends at university. Wits University, to be precise. Of those friends, more than a few had parents who had lived in exile during the worst parts of apartheid for the safety of themselves and their families. It was a more than sobering experience to view a very different side to apartheid.

One particularly sobering experience involved one particular friend and asking why his father didn't ever want to meet me when I went to his house to visit.

Simply put, I was told his father had had 4 brothers. Had. Past tense. They were all disappeared by the state. Not killed, not imprisoned, but disappeared. No bodies, no graves, no death certificates. No closure.

Of course, he never wanted to meet me.

As I grew, and learned, and saw more parts of South Africa, the more I could see that as much as things had changed, they had never changed enough. While apartheid, ruled by a white government, had technically ended, the reality was that the physical and emotional realities of apartheid continued to thrive. And on the open market of uncaring capitalism, what had been constructed as a racial system was now being ruthlessly exploited as a horrendously efficient mechanism of economics.

This became most evident to me when I spent some time working in sales in the south of Johannesburg. I got a contract with Katlehong High School. Driving from the white suburbs where I lived in the north of the city to the townships in the south, it became abundantly clear that still two countries existed inside one, two different realities, one of opportunity, one of fear, one of access to education and healthcare, and one without. And one day, a day of reckoning would have to happen. And the consequence of that would either be the elevation of one to the level of the other, but this would require work, effort, cooperation, and investment. Alternatively, we would see the destruction of the one to match the level of the other. Only through these two paths would equality be achieved.

Who cares about a white man's experience of apartheid?

The purpose of this introduction has been to show how effective the system was. In the next part, I will go into detail as to how Apartheid was developed, and the legal structuring of the system. However, this legal description of apartheid loses the details. It fails to fully paint the picture of how the system worked. It fails to explain why exactly so many white South Africans failed to resist a wholly immoral system.

And this is one of the dangers of totalitarianism. It controls every aspect of a person's life. However, it was also one of the weaknesses the apartheid government faced. Ultimately, it was not able to control every single aspect everywhere. There was a world outside apartheid South Africa. All it ever took to see the evil of the system was to step outside of the system.

In part 2, I will take a detailed look at the history and economics of apartheid. Finally, in part 3, I will argue, in what will in no way be controversial and in no way upset anyone at all, that apartheid is alive and well, and its awful specter is haunting Europe and almost every nation on earth. In some cases, it is once again a racial apartheid, or even an ethnic apartheid, but increasingly, it is becoming an economic apartheid.

Finally, I will ask the question that once upon a time was asked by some of the first Europeans to settle in the south of Africa: is the opposite possible? In place of these systems of division intended to dehumanize and control, either for ideological reasons or cold and capital reasons, can we harmoniously and peacefully integrate?