I drove into Old Havana in a pink Chevy convertible with pink and white striped leather seats and fins so sharp that even a shark would go green with envy. It’s exactly like the car my great aunt bought after her divorce, but had to sell when she remarried, as her new doctor husband said it was too sexy.

But sexy vintage American automobiles in Easter egg colors used as cabs and rentals fill the streets here in Havana, and what could be better than to arrive at the El Floridita, where Hemingway hung out at a time when these cars, now carefully tended for decades, were still new.

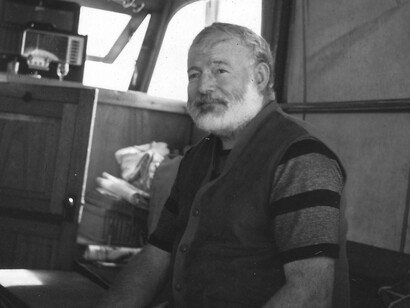

With its neon sign and lines of people waiting to get in, El Floridita is one of the main stops on my quest to follow in the author’s footsteps on this island where he made his home on and off for years. Sure, I’m decades late; he left Cuba for good in 1960, and by 1961, he’d put a gun to his head in Ketchum, Idaho. But you have to start somewhere, and Cuba, where he divorced (Paulette), married (Martha), divorced, and married again (Mary), and still found time to fish, pen The Old Man and the Sea, and drink, boy, did he drink, is the place to begin.

But let me take a step back and explain why I’m here at all.

I was a Gatsby girl in college. I loved the madcap Jazz Age figures in Scott Fitzgerald’s books, while Hemingway seemed, well, simple. And really, you couldn’t love both authors. After all, Hemingway famously insulted Fitzgerald when the latter remarked that the rich are different from you and me, and Hemingway said yes, they’re richer.

Hey, give the guy a break. Fitzgerald’s beloved Zelda was in a mental institution where she would ultimately die in a fire, and his career would soon fizzle out in a haze of alcohol and Hollywood contempt. Interesting when you think about it. Both men, celebrated authors and notorious drunks, would die lonely deaths.

“There was a fish,” I would say to my sophomore college boyfriend who loved Hemingway. “A big fish. A strong fish. He pulled, and it pulled back. It was a fighter. But he won. The fish wasn’t as strong as he. He caught it. And then, went to the bar and drank.”

My boyfriend, whose last name I’ve forgotten, did not think I captured Hemingway’s writing style at all. And he did not think I was funny. Though he acknowledged that I made a great daiquiri.

We broke up shortly after that, but not because of Hemingway.

It’s too bad I can’t remember that boyfriend’s name. Otherwise, I would write and tell him about my transformation into an admirer of Hemingway’s terse prose. He’d be surprised about that, but not that I was drinking daiquiris at El Floridita with its rather seedy pink exterior, similar to the dive bars I loved in college.

But you can’t let El Floridita’s exterior fool you. The interior harkens back to the grandeur of the pre-Castro era with its chandeliers, ornate bar, and frescoes of the Morro and La Cabaña fortresses and, in the dining room, a scene of Regla, a seaside town on the Bay of Havanna and the convent of San Francisco de Asís, all done in soft muted oils that recall the images of grand master painters seen in museums.

Hemingway is waiting for me when I walk in, sitting in his favorite corner at the end of the bar. Or at least his bronze statue is. Sometimes, a daiquiri, the cocktail he made famous and what most of the people are drinking here, is placed in front of the sculpture. It goes untouched, the ice melting and water dripping down the sides, until one of the tuxedoed bartenders whisks it away, soon to be replaced by another. That’s so Hemingway.

Daiquiris weren’t invented by Hemingway, nor were they invented in Havana, though when I mention this to the Hemingway aficionados who kindly offered me a place at their table, they seem skeptical. After all, it’s part of the mythology of the virile, knuckle-bruising, philandering, heavy drinking persona Hemingway honed to perfection. And who was I to disillusion them with facts? I didn’t say anything more.

But here’s what I know.

First of all, before it was the name of a drink, Daiquiri was a village about 14 miles east of Havana and played an important role in the Spanish-American War. But since no one really remembers much about the war from their high school history books, Daiquiri, the village, would have been forgotten if not for Jennings Stockton Cox, a mining engineer who in 1898 was working in the iron ore business in the Sierra Maestra Mountains near Daiquiri. To get Americans to work in Cuba, which, with yellow fever and extreme humidity and heat, was less than ideal, they were paid handsomely both in money and tobacco rations as well as rum. It was at the Venus Bar in Daiquiri that Cox refined a traditional cocktail called Canchánchara, a mix of aguardiente de caña, an unaged spirit made from sugar cane and sometimes molasses, limes, honey, and water, using ingredients he had on hand—Bacardi Carta Blanca, limes, and sugar.

The recipe for Cox’s drink was written down and passed along from bar to bar until finally reaching Havana, where it became a favorite drink of a drunken author.

Even bars in the old days of wild Havana closed at some point after midnight, and a man needed a home, and that’s where I head next.

The Iglesia de San Francisco de Paula, built in 1732, is a historic church not far from Finca La Vigia, Hemingway’s house in Havana’s San Francisco de Paula neighborhood, a little over 15 miles from El Floridita. It’s a stunning Baroque-style building, but I never heard that Hemingway spent much time there, so I pass by, heading to Finca La Vigia, the 1898 home he bought in 1939 from the royalties he received for his bestselling For Whom the Bell Tolls.

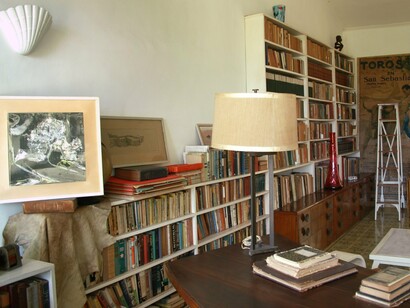

It's a museum now, frozen in time from when Hemingway lived here, and very lovely with large windows letting the sun spill into airy spaces and upon stylishly sleek furniture. There are bookshelves packed tightly with books, which I expected, and lots and lots and lots of animal heads mounted on the walls, which I should have expected but didn’t. Artifacts from his time here—an old Zenith radio, a manual typewriter, wire rim spectacles—are like a retro trip to the past. Pilar, his famed boat, which was moored at the fishing village of Cojimar when he died, is now on display on the grounds of his home.

I didn’t see any rum bottles in the waste baskets scattered around the yard, which I thought would add a touch of whimsy. After all, he famously stated his reason for drinking:

“An intelligent man is sometimes forced to be drunk to spend time with idiots.”

Well, that’s as good an excuse as any.