The term Mleccha in Hindu mythology does not denote a single community or tribe. Rather, it embodies a rich and nuanced cultural construct rooted in ancient India's worldview. Often interpreted as “barbarians,” “foreigners,” or “non-Vedic people,” the Mlecchas represent those outside the fold of Vedic dharma. However, their portrayal in texts such as the Mahabharata, Manusmriti, Ramayana, and Puranas reveals more than just a cultural othering—they are symbolic of boundary-makers, historical memory, and civilizational negotiation.

This article traces the origin, etymology, evolving portrayal, and socio-political symbolism of the Mlecchas in Hindu mythology and classical Indian literature. Far from being just "villains" or "outsiders," Mlecchas played complex roles—sometimes enemies, other times allies, and often silent witnesses to the rise and fall of dharma.

Etymology and meaning

The word Mleccha (Sanskrit: म्लेच्छ) has etymological roots that are debated among scholars. Most agree it is an onomatopoeic term used by early Indo-Aryans to refer to those who spoke non-Vedic languages—“those whose speech is unintelligible.”

In the Nirukta of Yaska (considered the oldest surviving text on etymology in Sanskrit), Mlecchas are people whose speech does not conform to the norms of Sanskrit or the Vedic language—thus marking them as non-Aryan. The term Mleccha was not originally racial but linguistic and cultural, pointing to deviation from the Vedic lifestyle.

Origin and historical field of reference

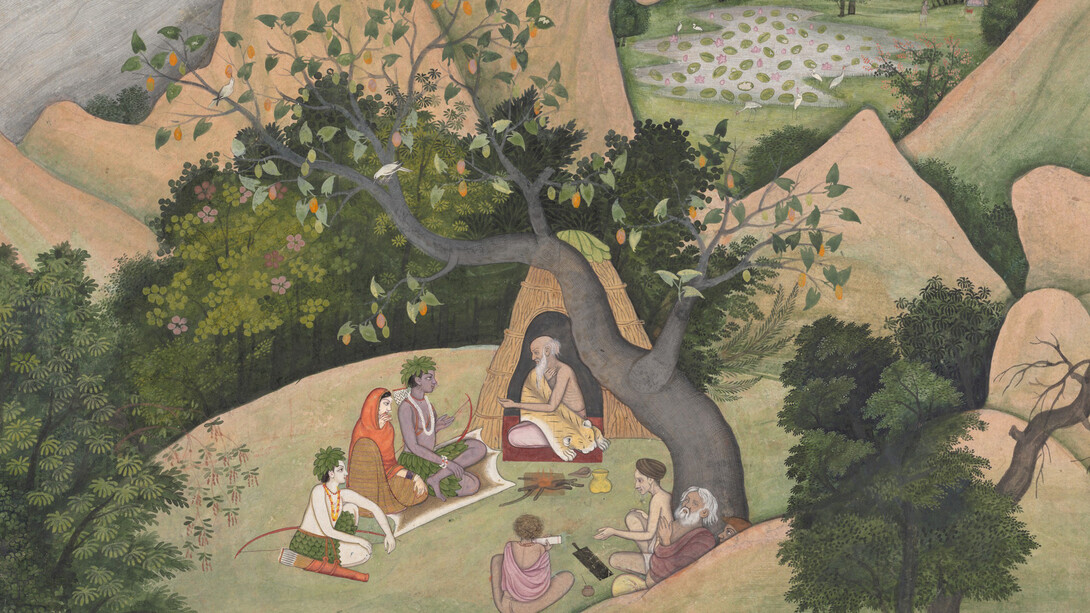

The earliest mentions of the Mlecchas appear in the Vedas and Brahmanas, but their more prominent emergence is in the epics and Dharmaśāstra literature. Geographically, Mlecchas were believed to inhabit regions outside the sacred space of Aryavarta, the land of dharma. This includes areas like the northwest (Persia, Central Asia), southern India (Dravidian lands), the northeast (China, Tibet), and across the sea (Yavanas, or Greeks).

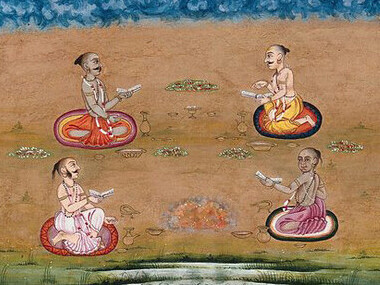

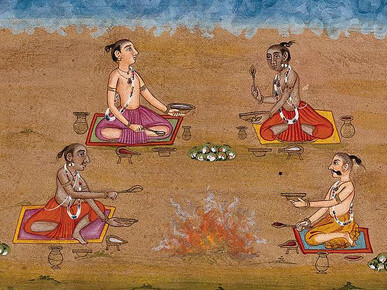

In Manusmriti (Chapter 10), Mlecchas are classified as degraded Kshatriyas—those who, through moral or ritual lapse, have fallen outside the varnashrama order. This list includes the Yavanas (Greeks), Shakas (Scythians), Pahlavas (Persians), and Chinas (Chinese), among others.

All those tribes in this world, which are excluded from the Vedic sacrifices, such as the Yavanas, the Kambojas, the Dravidas, the Shakas, the Paradas, the Pahlavas, the Chinas... are to be regarded as Mlecchas.

(Manusmriti 10.43-45)

Thus, Mlecchas could be foreign invaders, local tribes, or even Vedic communities that had strayed.

Portrayal in Hindu epics

The Mahabharata

The Mahabharata features Mlecchas both as antagonists and incidental characters. In Book 2 (Sabhaparva), during Yudhishthira’s Rajasuya Yajna, emissaries are sent in all directions to subjugate kings, including those of Mleccha descent.

Interestingly, during the final battle at Kurukshetra, Mleccha tribes are seen fighting on both sides, indicating their recognized martial status, even if culturally excluded.

In Book 6, Krishna refers to the future collapse of dharma and the spread of Mlecchas as part of Kali Yuga's arrival:

When Kali Yuga sets in, Mlecchas will rule the earth. Dharma will weaken, and unrighteousness will gain strength.

This prophetic tone paints Mlecchas as harbingers of decay, but not necessarily evil, just as a cosmic pendulum shift.

The Ramayana

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Mlecchas are mentioned as borderland dwellers and coastal inhabitants. When Rama sends out emissaries in search of Sita, Hanuman and his team are instructed to search in “Mleccha-dominated lands”, which included islands, foreign shores, and unknown cities.

This indirectly shows the geographical awareness of ancient Indians and their classification of the known world into “dharma-aligned” and “dharma-external” zones.

Mlecchas as ‘Asuric’ and ‘Adharmic’ beings

In many Puranic contexts, the Mlecchas are grouped with Asuras, Rakshasas, and other adharmic beings, yet they remain distinct. While Asuras represent internal spiritual conflict and cosmic opposition to devas, Mlecchas are more socio-political—standing for unassimilated people or rival tribes.

In the Bhagavata Purana (12.1), it is said that:

In Kali Yuga, Mlecchas will become kings of the world. They will be cruel, greedy, and impure, and will defy Vedic authority.

Again, this highlights the cultural anxiety of Vedic decline rather than biological racism. Mlecchas, in this light, are signs of a dharma imbalance that needs restoration.

Not all Mlecchas were villains: nuanced portrayals

Bali and the Daityas

King Bali, an Asura, is often grouped with Mleccha-like qualities, yet he is praised for his generosity and bhakti. Vishnu himself incarnates as Vamana to test Bali—not punish him. This shows that outside status did not negate spiritual greatness.

The Greeks (Yavanas) and Persian Mlecchas

Greek kings like Menander I (Milinda), who converted to Buddhism and debated with Nagasena (as seen in Milindapanha), show that Mlecchas were not inherently unspiritual. Even texts like the Mahabharata recognize the Yavanas as brave and skilled in battle, though they lacked the "shuddhi" of Vedic rites.

The Mleccha kingdoms and cultural memory

Several Mleccha kingdoms flourished historically. For example:

Kambojas: situated near modern-day Afghanistan.

Yavanas: Greeks, especially post-Alexander invaders.

Shakas & Kushanas: central Asian tribes who ruled parts of northern India.

Dravidas: South Indian civilizations, seen as Mlecchas in early Vedic texts.

With time, many of these were assimilated. For instance, Rudradaman, a Shaka king, became a great Sanskrit patron. Similarly, the Kushanas adopted Indian religion, minting coins with both Indian and Persian gods.

Thus, the Mleccha status was permeable, allowing for cultural negotiation and assimilation.

Symbolic significance of Mlecchas

The Mlecchas represent the limits of dharma—not evil, but uninitiated, unritualized, and uncoded. They are necessary “others” who define the borders of the sacred.

Symbolically, they represent:

The outer world—physically and metaphysically.

The unknown and foreign—a space of anxiety and curiosity.

The testing of dharma—where heroes venture and prove their resolve.

Cultural assimilation—as many Mlecchas later became patrons of Hinduism or Buddhism.

Mlecchas in Kali Yuga: prophecy or politics?

In Kali Yuga, Mlecchas are predicted to become dominant. This reflects both fear of foreign rule (such as invasions by Persians, Greeks, and Turks) and metaphysical concern about declining dharma.

However, instead of rejecting Mlecchas, Hindu mythology suggests they are part of cosmic cycles—as darkness before dawn, disorder before renewal.

Modern interpretations and misuse

Colonial Orientalists and post-Independence nationalists both misused the term —Mleccha"—either to otherize non-Hindus or to claim racial superiority. But the original texts are far more nuanced.

In today’s context, scholars advocate for reading Mleccha as a construct of difference, not hate. It reveals how societies define themselves by marking others, yet also engage in cultural fluidity.

Conclusion

The Mlecchas, far from being merely barbarians or villains, are essential players in the grand tapestry of Hindu mythology. They stand at the edges—watching, challenging, and sometimes even preserving dharma in unexpected ways. Their story is not just of exclusion but also of transformation, contact, and dialogue.

They are not static outsiders but dynamic reflections of how civilizations perceive change, foreignness, and the evolution of values.

In the dance of light and shadow that mythology stages, Mlecchas are not demons but mirrors—showing where dharma begins and where it might be tested, or even reborn.

References

Manusmriti, translated by G. Buhler (Sacred Texts Archive).

The Mahabharata, Critical Edition (Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute).

Valmiki Ramayana, Gita Press Edition.

Bhagavata Purana, Book 12.

Yaska's Nirukta (On Etymology).

Romila Thapar, Cultural Pasts: Essays in Early Indian History.

D. N. Jha, Ancient India: An Introductory Outline.

Sheldon Pollock, The Language of the Gods in the World of Men.