Even before the realization that he would become an artist, Macaparana already was one. In early childhood, he eagerly volunteered to restore the paintwork on the stalls used for popular feasts in Mr. Estêvão’s park. He would attentively follow the family meeting with the wall painter to discuss the colors of the facades before the festivities. He used chalk to fill his notebooks with drawings, lines, and designs - a prolific poetics that remains to this day.

Macaparana began his career crossed by the landscape of the Northeast of Brazil, nourished by the earthy colors of the arid region, adding surrealist touches to territories painted in gouache in the 1970s. To the attentive gaze, geometry was already present in the constructions, it was a compositional part of the figuration. When his poetics turned toward the incursion of blocks of color and a more inexorably geometric approach, there was no cause for surprise, they were complementary, they had been present in his imaginary since the platibandas1 and popular stalls. Geometry was his imagetic universe and became his materic living, notes from the same score, the same plastic investigation.

Before becoming material, music is composed of a modular system of human thought, just as art is. A musical score is a graphic record, with sounds translated into visual symbols, whether notes, pauses or compasses. Macaparana’s poetics resemble a musical score: they are visual symbols that do not translate sound vibrations, but suspend time; they are outlined in lines, circles, squares, rectangles, and more, in invented geometric shapes, projecting a rhythmic visual composition.

The artist starts from the basic unit, the precise point, which becomes an infinite set of points aligned in a straight line or circle. The point marks the space. Analytical geometry, however, is only touched upon, his geometry is not rigid, but rather rhythmic. He understands himself as a Dadaist, operating in a poetic style that allows for experimentation that blends with architecture, musicality, and sculptural production in macro and micro dimensions, as in the creation of jewelry. Paradoxically, his firm dash is also loose and inventive, so that the drawing expands into space and the sculptures demonstrate an interest in form and the interaction of light with matter.

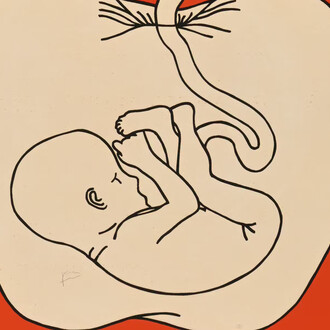

The drawing and the paper are fundamental as a starting point, they are a support and extension to amplify the point and the line, in which the line echoes in space and returns to the paper, in an eternal cycle of the line being pulled, just as Ariadne of Crete, daughter of Minos, did when she gave Theseus, moments before his entry into the Minotaur’s labyrinth, a ball of yarn so that he could find his way back. Ariadne’s thread evokes the guidance and method that leads the way and allows one to navigate the labyrinth of chaos. The line, the thread, is at all times a visual element, a method, and a poetics.

Macaparana, with his skill and technical variety, uses pigments mixed with acrylic paint, projecting prepared and singular colors with a velvety texture. There is a certain echo of Paul Cézanne, particularly in terms of the longing not to be categorized, marked by the desire not to have to choose between sensation and thought. In one of his essays, Maurice Merleau-Ponty ponders Cézanne and his doubts, suggesting that the contours of objects, like the lines that define them, do not belong to the visible world, but rather to geometry. When an apple is drawn, it becomes a thing, and yet it is nothing more than the ideal boundary to which the sides of the apple extend in depth, given that without an outline it would not be an apple and would therefore lose its identity. To mark only one would be to sacrifice depth, that is, the dimension that gives us the thing per se, not stretched out before us, but full of reserves, allowing for an inexhaustible reality.

The essence of Macaparana resides in the experimentation enabled by the technique and poetics of his highly versed gaze, it lies in the spontaneous order of perceived things, in the between two and three dimensions. The exhibition features previously unseen works on linen mixed with cotton, in which what is painted becomes a volume over emptiness - an expansiveness that is not embodied, demonstrating the dexterity of the gesture. Another series that emphasizes the artist’s range is the mobiles, suspended sculptures that allow a complete view of the materiality, which in all its facets bursts out of the grid into space.

Macaparana’s volumetry is permeated among diverse mediums, on paper, on canvas, on cardboard, in steel and in wood. Faced with research that has already been so thoroughly investigated in art history, between geometries and abstractions, his creative gesture is recognizable, and he appropriates and understands the liberating act of working in a field that allows him to navigate. Any rigid category is insufficient for the artist. What is conceived in the exhibition space is the reflection of a six-decade trajectory, a fascinating Macaparana’s aesthetic geometric weave, a radical hermeneutic act of continuing to find enchantment in the creative act.

(Text by Mariane Beline)

Notes

1 A platibanda is a low parapet or decorative strip that conceals the roofline of a building, very common in the northern and northeastern regions of Brazil, it is often brightly painted and ornamented, adding an elaborate touch to the façade.