As I (among others) have written before, much scholarship on Ottoman heritage management has framed the emergence of preservation, antiquities law, and heritage consciousness as originating in the 19th century, attributing initiative to European influence or colonial models. What tends to receive less attention is how material culture (for instance, ruins, relics, architectural fragments, etc.) functioned long before that as objects of value and as symbols of power and contention.

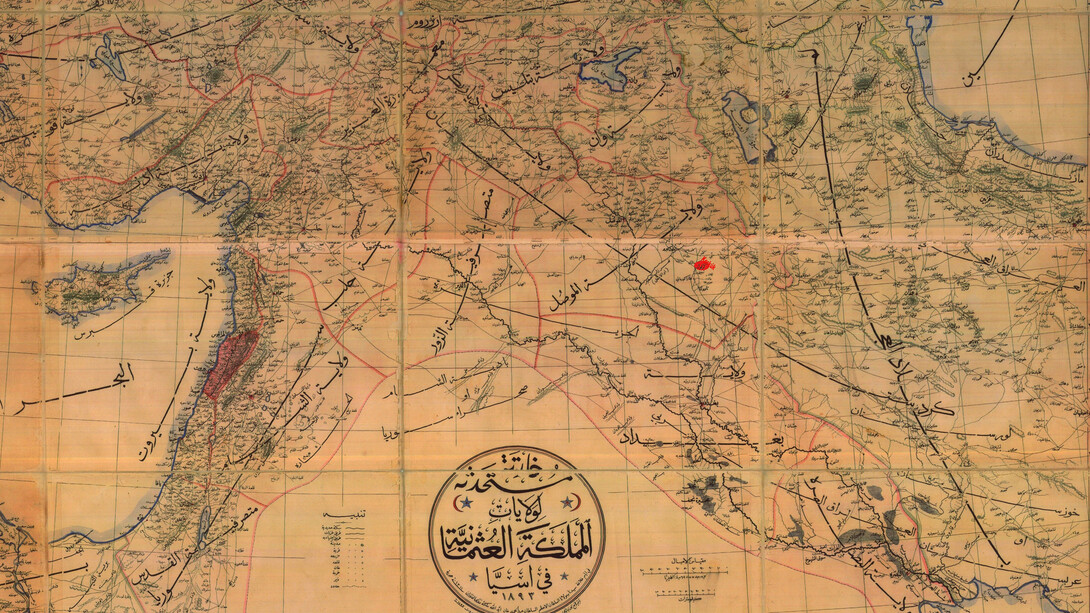

This article is a follow-up on my previous piece, which discussed how these objects and symbols comprised evidence of heritage consciousness in the Ottoman periphery long before the emergence of formal heritage management legislation. Specifically, this article considers how elite and state authority intersected with public agency and centred around things of the material past in the Arab provinces and Ottoman imperial centre during the early modern period (between the 16th and 18th centuries). The aim is to explore the ways in which elites, governors, religious authorities, and ordinary communities deployed, protected, contested, and protested over material objects, participating in acts of cultural governance.

One example is an episode in Constantinople involving Thomas Roe, the British ambassador, whose attempts between 1621 and 1628 to remove relief sculptures from the Golden Gate (constructed of Byzantine spolia, or sculptural fragments) were met with resistance from religious leaders, soldiers, and local officials. The removal had logistical challenges, of course, including the need to construct scaffolding and recruit personnel, but the greater challenge came from the obligation to secure permission from the Sultan’s representative. Despite no formal heritage protection legislation, the state resisted the foreign extraction of material culture due to fear of religious and symbolic consequences.

Similarly, in mid-18th-century Damascus, the al-ʿAzm family, renowned elites, recycled columns, stones, and even monuments (toppled and standing) in order to build their new palace in the city centre. The diary of Ibn Budayr records that this provoked “much havoc” among the public, and that the community objected vehemently to the appropriation of these architectural components. Ordinary people saw the destruction or removal of ruins as an infringement upon shared memory that exceeded the rights of the powerful family. This tension between elite appropriation and public sentiment suggests that material relics and ruins carried moral weight as well; despite being a common practice around the Mediterranean and across the Byzantine and Ottoman worlds, the practice of reusing spolia (historic sculptural fragments) for modern building was at times criticised as unethical appropriation of cultural property, sparking open protest and outrage.

By focusing on these cases, this article does not deny the importance of later formal heritage law or reforms, even those that were explicitly inspired by developments in Europe. Rather, it seeks to foreground a set of earlier, more contested, and more lived relationships between heritage, power, and public values. It shows that authority over heritage was never uncontested: elites used it to assert prestige and legitimacy, ordinary actors had expectations and moral claims, and communities resisted when heritage was threatened. In doing so, this article contributes to our understanding of how heritage in the Ottoman world was as much about power, identity, and protest as about preservation.

As a bit of background, the early 18th century in Ottoman Iraq marked a period of dramatic change in the relationship between central authority, provincial elites, and the symbolic use of material culture. Baghdad and Basra became domains of the Georgian Mamluk pashas - governors who exercised considerable autonomy while still acknowledging the suzerainty of the Ottoman Sultan.

Hassan Pasha (1704-1723), followed by his son Ahmad Pasha, established a mamlūk household that not only managed military and administrative functions, but also carried out public works, architectural patronage, and infrastructural projects (for example, Hassan Pasha’s renewal of the al-Sarai Mosque) that shaped urban identity. These rulers, while not fully independent of the Porte, controlled taxation, trade routes, and often mediated between local tribal powers and central Ottoman demands. Their rule extended beyond Baghdad to include Basra and much of Kurdish Shahrizūr. Trade from Basra toward the Persian Gulf and into the Arabian Peninsula and India enabled economic networks that supported both political authority and cultural contact. European travellers in the 18th century described Basra as a prosperous mercantile town with a vibrant commercial life and merchants from many parts of the Persian Gulf, Arabia, and Mesopotamia.

Meanwhile, political threats (external and internal) shaped the appetite of elites to assert identity and prestige through material culture. The rivalry with Persia constrained Ottoman control, and provincial governors often found themselves responding to both military pressures and managing symbolic legitimacy at home. The autonomy of provincial elites was tied to their ability to project order, display patronage, maintain monuments or ports, and sometimes prevent loss of artifacts or material legacy to outsiders. This function was as much symbolic as political, and its importance often increased in times of political turbulence or upheaval.

Thus, during the period from the early 1700s through to the late 18th century, authority in Ottoman Arab provinces was not monolithic or homogeneous. It was sustained by a complex system of elite patronage, economic networks (trade, ports), religious and urban responsibilities (pilgrimage, infrastructure), and public expectation. The physical environment (including buildings, relics, ruins, and shrines) was deeply embedded in political legitimacy and communal self-understanding.

This background situates the case studies discussed as episodes of protest, resistance, and negotiation, embedded in a system where power over heritage was exercised, contested, and shaped by both rulers and ruled.

Similarly, relics and sacred objects also served as sites of authority and contestation. In Basra, pilgrim relics such as those claimed to be connected to the Prophet or saints were frequently objects of veneration, and their possession, display, and sale often involved elite figures or religious notables. In such contexts, authority over these relics was rarely centralised; ownership or custodianship could rest with private families, shrines, or individual community figures, and yet, because of their spiritual or symbolic importance, both state and local actors showed concern over their treatment. Even when authenticity was doubtful, the possibility that a relic might be genuine was enough to confer moral or cultural authority to those who held or protected it.

These case studies illustrate that authority over heritage in the Ottoman Arab provinces (and imperial centres) was neither unchallenged nor unidimensional. Elites used material culture for assertions of prestige, legitimacy, or spiritual leadership, but needed to negotiate local sentiment and public values. Ordinary people, religious authorities, clerics, and observers like Ibn Budayr played roles in resisting what they saw as misuse or disrespect of heritage. The public response to spolia reuse in Damascus and the thwarted extraction of sculptures in Constantinople reveals that authority over heritage was a site of social negotiation, not the top-down imposition of policies imported from Europe.

While state policy or formal heritage law, especially before the mid-19th century, was not yet fully refined, these episodes show that authority, power, and public agency interacted around heritage long before formal legislation. The contestations over removal, reuse, and display of material culture highlight both the potency of material heritage as a political resource and the capacity of communities to assert their values in defense of what they saw as the common good.

From Thomas Roe’s failed attempt to extract relief sculptures from the Golden Gate in Constantinople to the al-ʿAzm family’s reuse of spolia and the outcry it provoked in Damascus, we see that elites, religious authorities, and ordinary people all played roles in shaping what material culture meant, who could use it, and for what purposes. These episodes suggest that even without formal legislation, heritage objects both shape and are shaped by confrontations between elites and the public.

State actors and provincial elites did indeed use material culture as symbols of legitimacy: relics stored and displayed to reinforce spiritual leadership; architecture incorporating ancient stones to express continuity with the glory of the past; and monuments and ruins functioning as markers of historical presence. Yet this symbolic usage was always mediated by communal values: the respect for ruins, the fear of spiritual or moral harm in their removal, and the integrity of local memory, which could also manifest in public protest, religious objection, or resistance. Ordinary individuals and religious communities were not passive consumers of heritage but active guardians or critics when material heritage was threatened or appropriated.

These dynamics overturn to a certain degree the traditional narrative that locates Ottoman heritage consciousness in the 19th century under European influence. Rather, what emerges is a more layered history: one in which the early modern Arab provinces under Ottoman rule exhibited attitudes toward material culture that combined practical, spiritual, and commemorative values, and in which authority over heritage was exercised, challenged, and negotiated long before formal heritage laws were codified.

One implication of this perspective is that scholars should avoid treating “Ottoman indifference” as a default condition, especially for the Arab provinces. Too often, historical narratives assume a homogenised indifference, downplaying the significance of local agents, of community values, religious practices, and memory. Another is that heritage in this context can be understood as a field of contestation rather than one of either preservation or neglect. The role of religious relics, of pilgrimage, of poetry, of ruins, of spolia, of public voices -all these matter for understanding how communities valued their past, even when formal state policy was nascent or underdeveloped.

In this way, material culture becomes a lens through which we can see how power was exercised, how identity was asserted, and how community agency resisted extraction or removal not just materially, but symbolically. These observations open up pathways for further enquiry about the transition into the 19th century and about how today’s heritage law and attitudes build on or diverge from these earlier practices.

In conclusion, authority and material heritage in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire were entwined with public values, with contested claims, and with lived experience. These findings suggest a revised understanding of how heritage was experienced and how it functioned under Ottoman rule as something deeply invested in by many, contested by some, and meaningful to all.

References

Anderson, Benjamin. “‘An alternative discourse’: Local interpreters of antiquities in the Ottoman Empire”. Journal of Field Archaeology 40, no. 4 (2015). 450-460.

Athanassopoulos, Effie F. “An 'Ancient” Landscape: European Ideals, Archaeology, and Nation Building in Early Modern Greece”. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 20:2 (2002). 273-305.

Bahrani, Zainab, Zeynep Çelik, and Edhem Eldem. 2011. Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753-1914. Istanbul: SALT.

Çelik, Zeynep. 2016. About Antiquities: Politics of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Deringil, Selim. 1998. “The Ottoman ‘Self Portrait’” in The Well-Protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire 1876-1909. London: I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd. 150-165.

Deringil, Selim. “Legitimacy Structures in the Ottoman State: The Reign of Abdulhamit II (1876-1909)”. International Journal of Middle East Studies 23 (1991). 345-359.

Hanioğlu, M. S. 2008. A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kafescioğlu, Çiğdem. 2009. Constantinopolis/Istanbul: Cultural Encounter, Imperial Vision, and the Construction of the Ottoman Capital. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press. 1-10, 178-206.

Leeson, Madison. 2025. Heritage and Legitimacy: Cultural Governance in Modern Iraq. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Sajdi, Dana. 2013. The Barber of Damascus: Nouveau Literacy in the Eighteenth-Century Ottoman Levant. Stanford: Stanford University Press.