There is no greater proof of true nobility than that which is based on ethical-moral principles.

(Goethe)

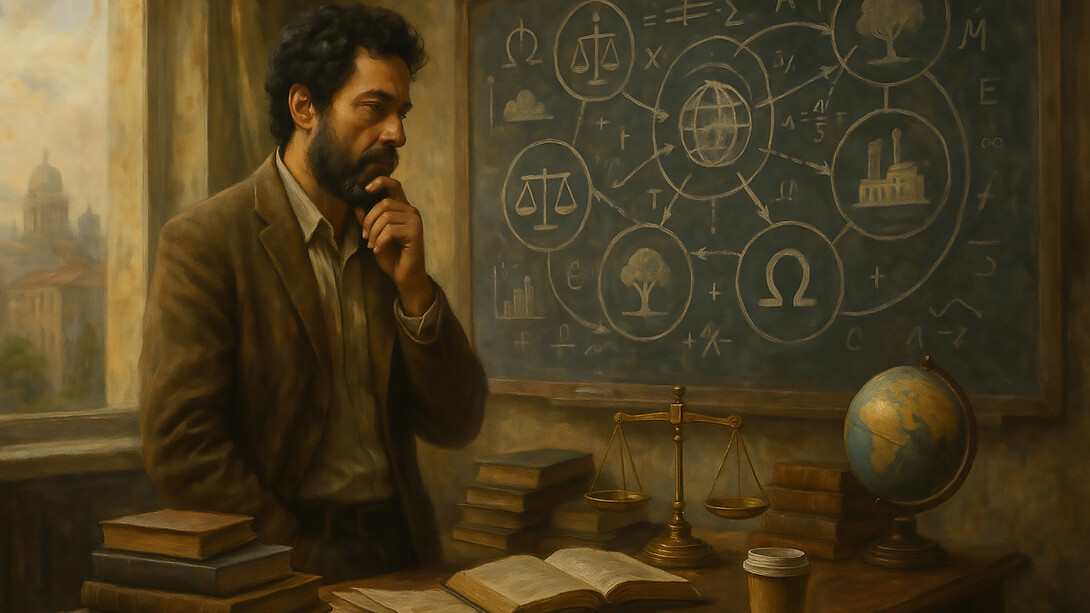

Philosophy is the culture of the mind and basis of intellect, which emanates from philosophical reflection.

(Cicero)

Fidel Gutierrez Vivanco is a Peruvian philosopher who imprints philosophy on all of his creations. He is a frequent contributor to Meer. His latest book provides a timely road map for socioeconomic consideration at a time when innovation is a key regulatory and policy concern in most industries, including healthcare, pharmaceuticals, food, agriculture, telecommunications, and artificial intelligence. His concern is how a business can build resilience in an uncertain world of markets and ensure progress.

Yes, the climate crisis is fueling Earth’s extreme wildfires. But the scientists also want you to know—it’s not too late to act. Even so, as the road to COP 30 in Belém, Brazil, shortens, the sense that such summits do not deliver much increases. My question is how we can bring balance in investment between population and individual curative health spending to give the ugly duckling public health in an arena dominated by the big business of clinical medicine? A question that should be asked is if this approach can be helpful at home in Peru in its recent spike in crime?

In this case he examines the creation of structures that perpetuate purposeful energy that goes beyond engaged individuals and an organization's life cycle. He says that the Rockefeller Foundation shows this conservation: John Rockefeller’s original philanthropic purpose (E) has been conserved for over a century through successive transformations into global health and scientific development legacies (M). He says that the same principles of dependence and interaction that kept the East India Companies stable throughout the 17th century also explain Google's success in the 21st century, demonstrating their timelessness.

He frequently refers to the "soul" of company packaging in terms of organizational culture, fundamental values, authentic purpose, and integrity in decision-making. Consequently, the commitment of Patagonia to environmental conservation guides its every business decision. The Montreal Protocol exemplifies this principle: it transformed the ethical energy of ozone layer protection (E) into concrete implementation systems (CFC elimination). The notable benefits in atmospheric recovery (matter) conserved and amplified the original ethical energy, financing, and justifying successive cycles of global environmental protection.

His overall message is that good is not just a moral aspiration but a scientific law inscribed in the very structure of reality. His gift is an ethical formula, which is not just a business model or a management theory but a philosophical reminder of something deeper and more universal: a gift of hope. Maybe the poets are correct when they tell us that the road to development is a bit like the road to Ithaca, with many ways to develop, but none that will get you there, so it is better to travel hopefully than to arrive.

Global risks landscape: A Brilliant interconnections map.

Global risks landscape: A Brilliant interconnections map.

I think of ethics as a set of principles that add value to any process, while morals are more personal and shape behavior. Business ethics are the set of principles that guide the behavior and decision-making of companies and their employees from apex to the working base. The more trust and fairness promoted in business operations and the greater the quality of their sold products, the more confidence I would think it would add to both would-be shareholders and customers of any company. I would think that a shareholder in a company would be mainly concerned about the return on his investment, and that a customer’s interests would be on the cost and reliability of its product, neither giving much thought to ethics.

The author states that ethical companies aren't "prettier"—they're mathematically smarter, and that doing good isn't a philanthropic act but the most solid strategy for building organizations that transcend time. He tells us that there is a unique framework in the universe that governs all stable systems, including businesses, and contends that the laws governing energy and matter in the physical universe also govern business success. He qualifies it by adding scale in the transformation of energy into matter that fans out from total inefficiency (zero) to perfect efficiency (one). It is further qualified by adding coherence between saying and doing. In this sense, his normalization process is alphanumeric, where saying can be zero and doing can approach one.

What is not said is how stable systems became stable, why a business has a life cycle, and how its longevity is constrained by substandard ethics. For example, in his reference to Volkswagen’s blind spot, he designated the Dieselgate fraud, which caused reputation erosion. Destruction occurs when operations (matter) are forcibly separated from ethics (energy), creating an artificially sustained system that collapses under its own incoherence. This forced separation generates unsustainable structural tension, where the organization tries to maintain appearances while internally operating in contradiction with its declared values.

The magnitude of the final destruction is proportional to the degree of separation between E and M that the company artificially maintained before collapse. Volkswagen forced this separation: its fraudulent software operations (matter) were completely separated from its declared environmental ethics (energy). When the separation became unsustainable, the collapse was proportional to the scale of the deception.

Bhutan’s development philosophy recognizes the need for balance between population needs and available resources and now can be viewed through Fidel’s ethical lens. Bhutan’s policies strongly reflect philosophy and are designed around planetary constraints, which are not to be bypassed. Bhutan’s citizens have a constitutionally guaranteed personal happiness. Bhutan stands as a global benchmark in its official rejection of GDP as the sole measure of progress. Since the 1970s, the country has embraced Gross National Happiness (GNH), a development philosophy structured around nine domains, including psychological well-being, health, education, good governance, and ecological diversity (Ura et al., 2012). This multidimensional model is designed to ensure that material growth does not come at the expense of spiritual and environmental integrity.

The country is carbon-negative—absorbing more carbon than it emits—and it is directed by its constitution to preserve at least 60% forest cover (Royal Government of Bhutan, 2008). To minimize cultural and ecological disruption, tourism is limited, and all national planning must pass through a GNH policy filter. It does not reject economic growth, but it prioritizes social development, targeting maximum good for the maximum benefit of the population in a continuum. For the record, I give Bhutan a high K.

This book is an ambitious welcome to the ethical revolution, where ethics is not simply an add-on to business but its driving force. It is not a book for idealists. It is portrayed as a journey along a path that begins with a philosophical question and ends with a scientific formula. Sustainability is not a destination but a philosophical act, not a strategy but a consequence. This is about a letter, the capital K, that captures a fleeting phenomenal concept designated ethics in business. While having the character of a constant when attached to some business, it takes on another value for another. The "Economy for the Common Good" philosophy (E), although initiated in small businesses and cooperatives, transcended those original material implementations (M) to influence European legislation, corporate certification systems, and the discourse of large corporations, demonstrating the timelessness and propagation capacity of its transformative energy.

You might think that the author is a confidant of business boardroom affairs, that he offers advice to the corporate world, and that he rubs shoulders with captains of industry. Not so! He is a Latin American philosopher hell-bent on quietly making a bitter world better, with greater prosperity for all, not by improving business ethics but by proposing ways to transform the focus of ethics from principles to a practical tool. In one sense, this book projects a paradox; on the one hand, in its complexity, on the other, its straightforwardness. The complexity is haphazardly spread over the book cover and may scare away some readers. There are symbols of summation and integration, equations with derivatives and square roots in the denominator, and sine waves. It shouldn’t. Its simplification helps understanding, which is a result of organization. Forewarned is forearmed!

There will be many objections to Fidel’s approach and much discussion from his dimensionless K to his, I would say, needed (ongoing) ethical revolution and given Ethical Formula: E = k · I could say that we know how decisions are made, and we strive to know in what ways and how they can be made better either in conditions of certainty or in uncertainty within or without bounded rationality. A nitty-gritty scientist might object by saying that his formula reflects E=mc², which makes c² a constant equivalent to k, a variable between systems, and can be manipulated within any systems.

The ethical revolution has already begun, says the author as he puts its equation in the readers' hands. It also comes with a warning that returns us to K, which can become dangerously low in various ways, as when decisions contradict values, when profit is the sole metric, or when talent turnover is high. If k is HIGH (>0.8), the company is resilient, innovative, and enduring. If k is Low (<0.5), the company is unstable and temporary. High K’s are allotted to Patagonia and Tesla.

Low K's go to Enron, Volkswagen, and WeWork. Enron, holding more than $60 billion in assets, was involved in one of the biggest bankruptcy cases in American history and generated much debate as well as legislation designed to improve accounting standards and practices, but with little discussion on ethics. As of today, though, while Tesla has just sold a record number of cars, profits have dropped by 37% year-on-year, with high spending, and the effects of tariffs and competition are making vital materials more expensive.

In trying to find some close philosophical parallel but not equal, perhaps Spinoza's insights into ethics will suffice. His worldview of reality leaves us with a guide to the meaning of an ethical life, but so do Moses and the 10 Commandments. Spinoza presents thoughts on the nature of God, on mind and human emotions, on slavery (which exists today in additional forms), and on the competence to understand and to communicate (read neurophysiology). His thinking about the eternal is worth recalling, which is different from infinity, as is his speculation upon humanity's place in the natural order, the nature of freedom, and the path to attainable happiness, which are all in jeopardy today. Spinoza entertains the possibility of redemption through intense thought and philosophical reflection; Moses offers salvation through the Lord Jesus and Savior, while Gutierrez, and sensibly so, offers no such thing.

Sources

Fidel Gutierrez Vivanco.

Blunder on the Clyde.

Urgently appealing to the United Nations COP26.

Genocide, earthlicide and COP29.

Nikola Tesla cross-examined by Socrates.