The question of the roots of the nation is once again highly topical, albeit perhaps outside the mainstream. But what actually constitutes a nation? For the most part, only right-wingers who love the state and Christian conservatives provide an answer to this question. Left-wingers and liberals generally reject the question itself.

Ethnicity, shared history, ethnic ancestry, or the state itself are the points of reference for most conservatives and right-wingers. The nation thus becomes a ‘community of destiny.’ Personal choice and conviction are secondary. In these concepts, one's own nation can be welcomed or rejected, but it is virtually attached to people by birth.

Now, it is not difficult to criticize these concepts. Take the term ‘ethnicity,’ for example, which conflates biological ancestry with man-made culture and religion—just as woke trans activists today often conflate biological sex with man-made social roles. But what is the alternative to a vague community of culture or ancestry?

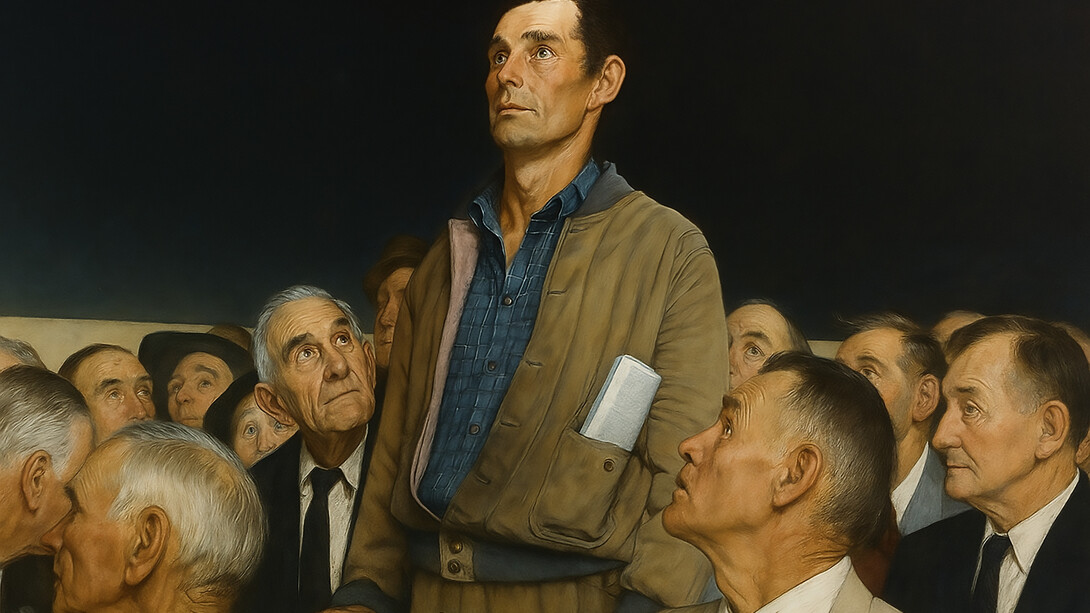

A nation as a moral idea

Surprisingly, American philosopher and author Ayn Rand offers an alternative here: the nation, born of a moral idea. She recognizes such an idea-based nation in the United States in particular. The great promise of ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’ is not a question of ancestry, but a fundamental philosophical principle. The United States is, therefore, at its core, a nation of immigrants and choice.

A shared attitude to life, born of frontier experience, deep-rooted skepticism of the state, and a love of the unbridled, creative individual, has grown out of this concept. The United States thus proves that it is possible to be a strong nation without being a tribal community based on ancestry.

Now, ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’ may seem to some to be a rather shallow demand. Here, too, Ayn Rand sharply contradicts this view and emphasizes the deeper insights behind this founding idea. Not only because it was radically new in the world of the late 18th century. First and foremost, she recognizes in this statement a person's ‘right to their own life.’ A person is not a means to an end for others but an end in themselves.

She recognizes civilizational progress precisely in individualism and privacy. She writes, ‘The entire life of the savage is public, determined by the laws of his tribe. Civilization is the process that frees the individual from the human collective.’ She therefore also praises the fact that the constitution only enshrines the right to pursue happiness, but not the right to happiness itself. For a right to happiness would mean a right to have others make one happy. That would be a gateway to bondage.

The nation of virtue

Ayn Rand goes even further than simply praising the United States for its constitutional ideals. Her love runs deeper. For her, the United States is also a haven for virtuous living. And virtue plays a decisive role in her philosophy of objectivism. However, she does not necessarily understand virtues in the same way as conservatives or even leftists. She considers Christian values such as self-sacrifice, gentleness, modesty, etc. to be life-denying. These are self-deprecating values that arise from altruism. In other words, from the philosophical concept that an action is only good and moral if it is performed to one's own detriment and for the benefit of others.

Altruism as an idea—often in the wake of collectivism—corrupts people, in Ayn Rand's view. It makes suffering and incompetence the central currency. The more irresponsible and bad a person behaves, the more they are given by their fellow human beings in an altruistic society. This is a phenomenon that we can observe every day in our welfare state: the responsible, disciplined entrepreneur who creates added value is plundered for the antisocial, permanently unemployed alcoholic with three illegitimate children.

For Ayn Rand, the solution does not lie in state control or tribal group pressure. And certainly not in ‘social patriotism.’ Whether someone has the same skin color is irrelevant to their virtue. And a beneficiary does not become better just because they can complain in their own language about how oppressed, discriminated against, or miserable they feel at the moment. They are no less a follower just because they like the same food or read the same history book at school.

Even being ‘proud’ of one's own nation is, for them, mostly parasitic free pride. It is rarely based on one's own achievements but rather on appropriating the achievements of others. Those who are not poets and thinkers do not have the right to be proud of being ‘poets and thinkers’ just because they live in a region where Goethe and Schiller once walked. Pride is an expression of individual virtue. It must therefore also be earned individually. For Ayn Rand, Pride Month and Pride Month are thus on the same level as the mentality of unearned beneficiaries.

A spiritual rebirth for Germany?

But why think about all this? A nation can only survive in world history if it has the capacity for renewal and its unifying element endures. Goethe, Schiller, and Lessing have long been buried; restored Art Nouveau buildings are not the future, and a dying or dead car industry offers no economic prospects. While the United States renews itself time and again with its ageless promise of freedom and achievement—whether with the Apollo program or as the global center of social media—Germany clings not to a timeless idea but to outdated baggage. And so do its supposed advocates.

Prussia is dead, the emperor long deposed. No nostalgic, wistful flag of pride will restore it, no matter how large an imperial eagle is printed on it. No free pride, just as no free courage, will create a new generation of virtue. And deep down, every thinking right-winger knows that the national community will not return. Conservative love is not for the nation but for its fading past.

So the question of the day is not whether we choose a nostalgic nation of Germanic age-related diseases or woke self-abasement. The question is not whether we should feed virtuous and unproductive Germans or rather virtuous and unproductive people from the rest of the world. The question—if we follow Ayn Rand—is: a nation of ideas or not? A nation of the best, the proudest, the bravest, the most productive, and the most honest, or a nation of those born together?

Ayn Rand answered this question for herself and never regretted her ‘choice of nation.’ She has gone down in American history with her works, which have sold millions of copies. She never betrayed her love for the fundamental principles of the United States. She always remained a patriot of virtue and freedom. And she always remained convinced that individual thinking and judgement determine the character and value of her fellow citizens for her own life—not the grace of being born into the right family or sharing the same history book.

This article was written by Max Remke. Max is a freelance writer, YouTuber, and co-founder of the German youth organization Liberty Rising, as well as the German Ayn Rand Society.