The art of arms has changed radically in the early modern period in Europe. Firearms were introduced during the 15th century, transforming the practice of warfare. It is believed that bladed weapons became obsolete and irrelevant on the battlefield. Arguably, this may well be a matter of opinion rather than one of facts. The Early Modern period of European history was marked by the performances of the Spanish Tercio. This elite military unit was mainly formed by pikemen and swordsmen and was the Spanish army’s most dreadful land forces, especially during the Italian Wars in the 1490s and 1500s. The Tercio keeps being admired and compared to the Macedonian Phalanx and the Roman Legion.

But it is also true that fencing underwent dramatic evolution during the same period. Even though the use of such weapons grew in the civil life of aristocrats who wore them as part of their daily outfit. The period between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century (more rarely, the nineteenth) is remembered for the frequency of duels between individuals or small groups who belonged to the milieus of nobility. In the collective imagination, items of popular culture have left the memory of a particular type of sword, the rapier.

Rapiers emerged in Europe between the 15th and 16th centuries and are quite a distinctive feature of the early modern times as a single-handed weapon in contrast with the two-handed swords, which are associated with knights in armor and medieval warfare. The latter was popularized by literary and cinematographic works, especially of the medieval fantasy genre. Fans of J.R.R.Tolkien probably may think of the heroic Aragorn, who swung his sword Narsil/Anduril in ‘The Lord of the Rings,’ rushing to save Boromir, who blew his horn to call for aid, in what is very likely a rewriting of the death of Charlemagne’s nephew, Roland, who perished at the Ronceveau Pass on August 15th, 778.

Medieval sword fighting is thus associated with broad, heavy swords, which knights in armor swing with two hands. In the ‘A Song of Ice and Fire’ book series and the ‘Game of Thrones’ TV show, most knights, brigands, and men-at-arms wore such weapons. One exception is one protagonist who was instructed by a swordsman, which is indeed very Spanish-like.

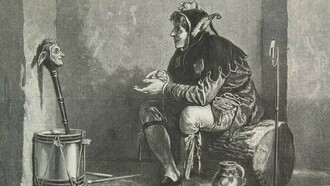

Thinking that swordsmanship rapidly declined at the end of the medieval period is, however, overstated. The art of the sword, rather than declining, probably knew its heyday in what could well be dubbed the ‘Age of Duels,’ eventually popularized by the literary genres of adventure and ‘sword stories.’ Besides the above-mentioned references, it is possible to quote other interesting titles such as Alexandre Dumas’ D’Artagnan Trilogy (‘The Three Musketeers,’ ‘Twenty Years Later,’ and ‘The Vicomte of Bragelonne’). Swordsmen were well portrayed in the ‘Commedia dell’Arte’ with the mask of Scaramouche, itself derived from another figure, Il Capitano (the Captain).

Il Capitano is one of Commedia's most ancient Neapolitan masks. It probably appeared in 1500. He is portrayed with Spanish clothes and most often wears a long rapier sword at his side. Another example worth mentioning is the intrepid Zorro, who boldly crossed his sword with the members of the garrison in the small pueblo of Los Angeles. Many children grew up with the Don Diego de la Vega / Zorro (Guy Williams), making fun of Sergeant Demetrio López García’s (Henry Calvin) protuberant belly in Walt Disney Studios’ version of the masked hero.

Invented by Johnston McCulley in 1919, Zorro (meaning ‘The Fox’) is known as a fine, if not the finest, swordsman of his time. In the late 1990s, a cinematic version, an aged version of Don Diego de la Vega (portrayed by Anthony Hopkins), instructed a wastrel, Alejandro Murrieta (Antonio Banderas), in the style of fencing that is known as Verdadera Destreza, thus training him to take the legendary mantle of Zorro. Though Zorro’s story is situated in the nineteenth century, the hero is proficient in this specific style of the sixteenth-century system of fencing.

The emergence of the ‘science of arms'

The evolution of fencing was due to the popularization of this particular type of sword, which is the rapier. Rapier swords are likely to have appeared by the middle of the 15th century in Spain and to have quickly spread in European aristocratic milieus. It was very successful in Italy, probably after it was introduced in the Southern country, the Spanish Habsburg-ruled ‘Reign of the Two Sicilies.’ It was adopted as both an ornament (in Spanish, the sword is known as the ropera and thus worn as part of the ropa, the clothes), as did Il Capitano in the ‘Commedia,’ and a ready-at-hand weapon in the occurrence of duels or aggressions. The rapier had the advantage of being single-handed (thus it could very often be complemented with the dagger) and therefore easily transportable. Its characteristics make it an arm to be used in a civilian context rather than on the battlefield, where broader two-handed swords and, more and more often, sabers of the cavalry were more frequent.

Fencing with weapons like the rapier required more skills and agility than the heavier equipment. Besides, it evidenced changes of modality in the idea of individual attitude, especially with regard to combat. The rapier swords represented a new aristocratic ideal. In fact, noblemen were to be educated in the different arts and sciences of their time, and that elegance in clothing reflected a more refined taste. It was the case of Jeronimo Sanchez de Carranza (c. 1539–c 1600 or 1608), the founder of the Verdadera Destreza. He attended the University of Seville, where he was educated in sciences and philosophy, besides becoming fond of poetry.

Reading his treatise, ‘Philosophy of Arms and Art of Genuine Dexterity,’ it is clear that Carranza was indebted to the legacies of Ancient Greece. Greek knowledge pervades his discourse on the art of arms. The Verdadera Destreza—or ‘Genuine Dexterity,’ better known as ‘true skill’—was elaborated in Southern Spain between the late sixteenth and the early seventeenth centuries by Carranza, who eventually reached the position of Governor of Honduras. It was perfected by his disciple, Luis Pacheco de Narváez (1570-1640), who became master at arms to King Philip IV (1605-1665). The Destreza’s legacy lasted until the early twentieth century, when sword-fighting seemingly was confined to sport. Carranza and Pacheco, after him, introduced a martial system that reflected the Baroque age. It was marked by the Scientific Revolution and the deep influence of the Renaissance’s humanism.

Just like the art of war in general, fencing evolved under the effects produced by the ‘scientific revolution’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Carranza used Euclidean geometry and applied it to the philosophy of arms. A great many of the early modern bore such titles as the philosophy, or science, of arms. It is during this period that treatises of fencing started to be printed in Italy. In the late 15th century, the Bolognese school rose to prominence among European fencers after the treatise by Achille Marozzo (1484-1553), who wrote the ‘Opera Nuova Chiamato Duello’ and thus laid the basis of the Italian way of fencing and, in the long run, Olympic fencing. Achille Marozzo was the instructor to important condottieri, among whom was the famous Florentine mercenary Giovanni dalle Bande Nere (1498-1526).

Camillo Agrippa’s oeuvres and works are more directly connected with the Verdadera Destreza. Born in Milan in 1535, Camillo Agrippa spent most of his life in Rome, where he passed away after 1595. An acquaintance of Michelangelo Buonarroti, he published a Trattato Di Scientia d'Arme, con un Dialogo di Filosofia (1553), which was praised for its innovative approach based on geometrical figures. Agrippa simplified Marozzo’s doctrine on guards and stances. He reduced guards from eleven to the eight basic guards used in modern fencing. According to Pacheco de Narváez, Agrippa’s geometrical approach to fencing was one of the sources from which Carranza drew inspiration for his ‘Verdadera Destreza.

The ‘philosophy of the genuine dexterity’

The main characteristic of the Verdara Destreza is its ‘scientific’ approach. That is to say, an organized corpus of knowledge. But a closer reading of the book also leads to defining its scientificity, considering the constant reference to mathematics, geometry, and savant works of this time.

First of all, it is the human body that is at the center of the discussion. More particularly, the treatise considers proportions and distances—probably drawing inspiration from the painter Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). Moreover, the treatise is one dealing with biomechanics. It has the premise that the brain orders or instructs the nervous system to move the body—an encephalocentrism inherited from the knowledge of Galenic medicine, disagreeing with Aristotle on this particular point. In this wake, the narrative structure of the treatise by Carranza is interesting. It is a scholarly conversation carried on by four fictional characters and divided into four Socratic (or, rather, Platonic)-inspired dialogues. Carranza himself impersonated the figure of the master (Chilarao), delineating the author’s ideals of the swordsman as a model of virtue, piousness, and intellectual elegance.

Indeed, the ‘Philosophy of Arms or Genuine Dexterity’ is meant to serve as a way of both Christian defense and offense. Therefore, the practitioner of the true destreza’s first and foremost quality should be his moral behavior and honesty. In the 1500s, there was no clear-cut shift away from medieval values of chivalry. Rather, it is possible to identify continuities that may change only as an effect of the revolutions that inaugurate the long nineteenth century, of which Eric J. Hobsbawm identifies the beginnings in the 1770s to the latest. To respond, Carranza's figure of the Master is, according to the Compendio de la Verdadera Destreza, later written by Pacheco, the poet Fernando de Herrera, the humanist Juan de Mal Lara, and the doctor Pedro de Peramato.

Eudemio might also well be the Duke of Medina Sidonia. All people, Carranza estimated, whose contribution shaped his ideal of the swordsman practicing the destreza. All in all, the central aim of this way of fencing is to distinguish it from other, ‘vulgar’ styles of destreza. It is this intent to cast light on the definition of true, genuine (verdadera) practices of arms that requires outlining rational principles grounded in philosophical and, therefore, scientific ideas.

One thing taken from Agrippa is the use of geometric figures, especially the circle. In this wake, the swordsman moves following angles and triangular moves to dodge the offense and strike the adversary’s central line. Similarly, Carranza also distinguishes narrow and broad stances according to the circumstances, obviously instructing how to better gauge distances to correctly dodge, parry, and efficiently counterattack, if possible, disarm an adversary. The footwork in the verdadera destreza thus differs from modern fencing's linear back and forths, resembling more the Filipino martial arts like Eskrima. There are speculations that Filipino martial arts were influenced by the Spanish ones during Spain’s colonial rule. Similar footwork is also present in modern boxing.

This short and partial account of some of the technicalities of the Verdadera Destreza highlights what may be the sign of the imminent and fundamental shift of the Scientific Revolution. That is, a mathematical interpretation of reality shifting away from the providential and godly reality of the Medieval Period and still lasting during Carranza and Pacheco’s lifetime. In some regards, the hypothesis that some elements of Galileo’s vision of the world were elaborated in a military milieu could be relevantly formulated if one bears in mind that the Destreza was published in 1582, and Agrippa’s treatise preceded it in 1553.

Between these and Galileo’s writing, there’s a common conviction that reality can be divided and segmented into geometrical figures and calculated precisely to provide an exact gauge of the dimensions of both man and the world. Another inspiration could well be Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. It may thus be in the arts of war and arms that the fundamentals of modernity could be found. And this may not be exclusive to Europe and Western civilization.

The science, or philosophy, of arms beyond Europe

Similar concepts to Carranza, Marozzo, and Agrippa could be found in the treatise on fencing and war tactics of the sixteenth/seventeenth-century samurai Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), ‘Go Rin no Sho’ or ‘Book of Five Rings.’ His 'Book of Five Rings' was published at about the time of his death. There are no documented links between the Verdadera Destreza and Musashi, and the oeuvres are separated by about sixty years. From a technical standpoint, the ‘School of Two Skies’ (NiTen ichi Ryu) has many common points with the Spanish style, like the use of two weapons (Katana and Wakisashi sabers) and similar footwork (similar to walking, instead of lunging, using a Yang and a Yin foot). Besides, they were written at the antipodes of the world.

If the Portuguese and the Dutch had substantial contacts with the Japanese, there are no clues that the Spanish had any relevant trades with Japan. Therefore, the common points between Musashi’s and Carranza’s views regarding the sword must be considered only coincidental. Musashi’s theorization of fencing happened at a time when Japan had gone through recent troubles but was then inaugurating a time of internal pacification under the hegemony of the Tokugawa Shogun. Nowadays, the legacy of the Go Rin No Sho is to be found in its applications in management more than in Japanese Ken Jutsu or Kendo.

Both the Japanese and the Spanish ways of fencing were crafted by men whose deep insight into the mastery of arms also reflected a period of distancing from supernatural forces and religious worldviews. Without, however, renouncing faith. Victory, in the duel or in the battle (the battle being, according to Musashi, an extension of the duel to large numbers), depended no more on the favor of God or the gods. It rested upon the use of a strategist’s or warrior’s own skills and the application of principles that enabled prevailing against adversaries who lacked real tactics. As Carranza wrote in the second dialogue, the False Dexterity (Destreza Vulgar) is pure chance. It is the genuine application of scientific notions and principles that leads to success, not prayers and supplications.

This is what Carranza essentially meant with the concept of verdadera destreza: the dexterity of the swordsman must be authentic, i.e., genuine. In a similar vein, Musashi recommends—in the ten principles that he outlined at the beginning of the Go Rin No Sho—to ‘worship the Gods and Buddhas without relying on them.’ Again, this did not mean abandoning faith. Yet, Musashi retained the shame of ignoring the gods in daily life and imploring their help in a moment when life and death were at stake.

The main and core difference is that Destreza relied on geometrical concepts to the extent of being also nicknamed ‘Euclidean’ fencing, while Musashi used a more metaphorical language, although he dealt with concrete examples. It is not that he or Japanese warriors/men of letters (who were very often the same people, like in the West) were ignorant of geometry and mathematics, or did not use them in the field of warfare. In this regard, the influence of China was felt sooner in Japan than it was in Europe. It is very unlikely that the Japanese had ignored geometry and trigonometry in gun fortresses and on the battlefield in general. In terms of approach, both masters rely on the respective Greek and Chinese theories of elements.

Carranza associates each sense with an element, whereas Musashi subdivides the chapter of his treatise into Earth, Water, Air, Fire, and Void, the latter being the synthesis of the former elements. In this regard, the Destreza was rather more esoteric than the NiTen school. Indeed, Miyamoto Musashi was a realist whose theories were grounded in his experience of combat more than in borrowings from Chinese classics. Superstition and divination were part of Sun Zi’s classical ‘The Art of War.’ Of course, many centuries separated Sun Zi from Musashi.

In the present state of knowledge, the Scientific Revolution is considered to have happened in Europe. Yet, authoritative historians like Joseph Needham have forcefully argued that Europe did not get to this revolution alone. She owed much to China first. But European (often synonymous with ‘modern’) science is more broadly indebted to India, the Islamic world, and ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Again, such similitude between these two systems is not materially connected, as far as we know. But it is worth underlining that rationality and rational thought emerged spontaneously in distant places, in different cultures, independently, and at more or less the same time.

Ideas may travel and cross long distances and be exchanged between distant cultures. But people are also able to reach similar conclusions and produce similar inventions independently. There are similarities in two systems elaborated by two single masters independently, thousands of miles away, in quite a short time span. Genius can spring out in different places at different moments.

An early modern aristocratic ideal: the sword and the pen

Jeronimo Carranza fits well in the model of the Baroque aristocrat. He combines the humanist interest in letters and sciences. Thus, he well personifies the humanist ideal of most military men during the Baroque Age. From a petty noble up to the king of Spain/Habsburg Emperor himself, it was considered that aristocrats had the duty to cultivate both excellent skills in the martial arts and excellence in literature and science. In a more peculiar way, this is what Don Quixote represented too: his quest as a knight was caused by his imagination being inspired by the many adventure books he happened to have read. On the other hand, this was also Musashi’s way: to him, warriors (Bushi) were familiar with two things, letters and swordsmanship. Their duty was to attempt to conciliate the Pen and the Sword.

References

Pacheco de Narváez, Luis: Compendio de la filosofía y destreza de las armas de Jerónimo de Carranza (1612).

Carranza Gerónimo de: Libro de Hieronimo de Carança natural de Sevilla, que trata de la Philosophia de las armas y de su destreza y de la aggressio[n] y defension christiana (1582).

Musashi, Miyamoto (Shinmen Bennosuke): Go Rin No Sho / Book of Five Rings (1645).

Agrippa, Camillo: Trattato di Scienza d’Armi (1568).

Marozzo, Achille: Opera Nova Chiamata Duello (Circa 1536).