Humans are the only species that celebrate. Anniversaries, family and religious rituals, conception, life, marriage, nature’s renewal, gods, the passing of each year, and death itself. Every ritual reminds us of mortality, and some show that finitude is part of life. Perhaps that is why we must fill it with meaning while we can.

Laughter helps articulate and process trauma and difficult experiences. It lightens their weight but allows their reality to exist instead of suppressing pain. Jewish jokes about the Holocaust (told by Jews in self-reflection, not to be confused with antisemitic mockery) or a family reminiscing at a funeral and recalling funny memories with the deceased both use laughter as pain relief.

Dance and joy go hand in hand. This feeling connects body and soul, creating a shared sense of belonging. Celebrations and weddings are built around dance. Even the animal world shows ritual dances. When movement is joined with emotion and ritual, it creates a celebration that can last for decades or centuries. It forges, strengthens, and sustains community.

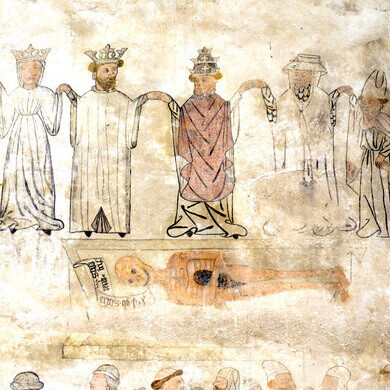

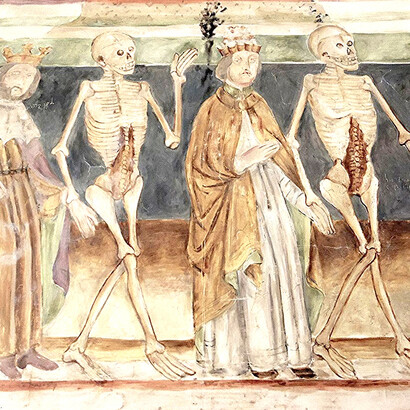

The Dance Macabre (or Danse Macabre), emerging in fourteenth-century Europe, embodies a collective response to the omnipresence of death during the late Middle Ages, particularly following the devastation of the Black Death. Representing death personified, leading individuals from all social strata into a communal dance toward the grave. The motif served as a reminder of mortality’s universality and as a means of social reflection. Beyond its visual and literary manifestations—in murals such as those of the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris or Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death woodcuts (1538)—the theme also served as a ritualized form of coping with existential anxiety.

From an anthropological perspective, the Dance Macabre transforms fear into a shared performance, creating a liminal space (Turner 1969) where social hierarchies dissolve and communitas emerges. The performative inversion of order mirrors the dynamics of carnival and mortuary rites, domesticating the terror of death through movement and humor. The motif’s endurance—from medieval frescoes to Saint-Saëns’s symphonic poem Danse Macabre (1874)—underscores its cultural significance as both moral allegory and communal ritual, expressing humanity’s ongoing need to ritualize mortality and affirm life through symbolic play.

If the Dance Macabre ritualized death through movement, then Jewish humor ritualizes survival through laughter. Both are forms of symbolic resilience: one transforms fear into choreography, the other into humor. Anthropologist Richárd Papp’s fieldwork among Jewish communities in Budapest shows how humor functions as a living cultural practice that negotiates trauma, identity, and belonging in post-Holocaust Central Europe.

In Papp’s ethnographic studies—conducted primarily within the Bethlen Square Synagogue community—Jewish jokes appear not as mere entertainment, but as tools of meaning-making and social repair. Through shared laughter, members of the community articulate the tensions between tradition and modernity, faith and doubt, and persecution and adaptation. Like the medieval Dance of Death, this humor acknowledges the inevitability of loss while asserting the continuity of life.

A central motif in Hungarian Jewish humor is self-irony. The recurring figures of Kohn and Grün—fictional archetypes of Jewish everymen—embody the paradoxes of Jewish existence under shifting political and social conditions. They express skepticism, moral intelligence, and adaptability. Self-directed humor allows individuals to remain within the community while also questioning it; it offers a form of critique that does not destroy solidarity. As Papp notes, even jokes that reference persecution or assimilation ultimately serve to preserve identity through play, transforming pain into cultural coherence.

Papp’s research also highlights the boundaries of laughter. The Holocaust, for instance, is rarely the direct subject of jokes within the communities he studied. Its enormity renders it unspeakable, resistant to humor. Yet its absence of humor is itself a form of collective expression—acknowledging the depth of trauma without trivializing it. In this sense, silence becomes part of the comic register.

Anthropologically, Jewish humor functions as what Victor Turner might call a liminal performance: a social space where norms are suspended and contradictions revealed, yet community is reaffirmed. Jokes are miniature rituals in which speech replaces dance, but the emotional logic remains the same as in the Dance Macabre: a communal processing of fear and impermanence. Both laughter and dance enable a confrontation with death that is not paralyzing but life-affirming.

Thus, Jewish humor—as described by Papp—demonstrates that laughter, like ritual, is an embodied cultural response to vulnerability. It binds communities through shared ambivalence and irony, transforming memory into endurance. In the aftermath of destruction, humor becomes both testimony and resistance—a reminder that to laugh together is, in itself, a form of survival.

This interplay of ritual, movement, and laughter underscores a fundamental truth about human creativity—the ability to transform suffering into meaning. Whether through medieval murals, synagogue jokes, or contemporary commemorations, these expressions embody continuity amid change. They reveal that culture’s deepest function is not to deny mortality but to dance with it, to speak and laugh through it. Every ritual, from the Dance Macabre to the whispered humor of Budapest’s Jewish elders, becomes a rehearsal for resilience—a living reminder that joy, too, is an act of defiance.

Bibliography

Papp, Richárd. “Have I Asked the Name of that Fish?”: Synagogue Humor in Contemporary Hungary. Jewish Folklore and Ethnology, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2024).

Papp, Richárd. „Anya, nem akarok a zsinagógába menni!” A magyarországi zsidó humor antropológiai jelentéseiről. Kultúra és Közösség, 2020.

Papp, Richárd. “But Where Is Kohn?” Modern-Day History of the Hungarian Jews in the View of a Jewish Community’s Humor in Budapest. RA Journal of Applied Research, Vol. 3, No. 12 (2017).

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine, 1969.

Huizinga, Johan. The Waning of the Middle Ages. London: Edward Arnold, 1924.

Holbein, Hans. The Dance of Death. London: John Murray, 1868 [1538].

Huizinga, Johan. The Waning of the Middle Ages. London: Edward Arnold, 1924.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine, 1969.

Vovelle, Michel. La mort et l’Occident de 1300 à nos jours. Paris: Gallimard, 1983.

Tarlow, Sarah. “The Archaeology of Death and Memory.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (2012): 163–179.