The French invasion of Algeria in 1830 is often viewed from the perspective of European expansion and colonial ambition. Yet, at the heart of the conflict was a resistance that would shape Algeria’s history for decades, led by a figure who is not always at the forefront of the French narrative: ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jazair. His leadership during the early years of Algeria's colonisation offers a complex portrait of resistance, politics, and struggle in the face of foreign domination.

The invasion and ‘Abd al-Qadir’s emergence

The French invasion of Algeria was part of a broader strategy to reclaim national prestige following the Napoleonic wars. For the French, the conquest was framed as an extension of their empire, an expansion into North Africa that would bring Algeria under their control. However, for the indigenous Algerian population, this was the beginning of a profound crisis.

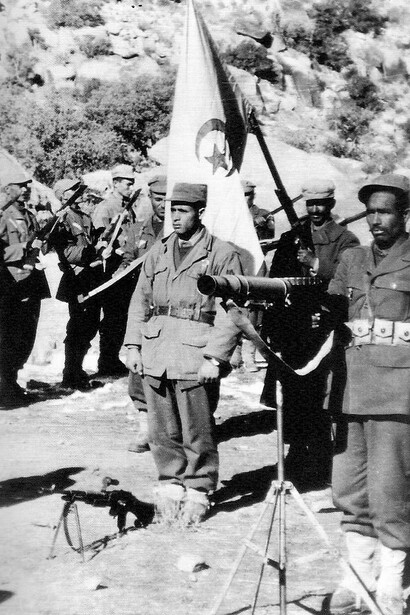

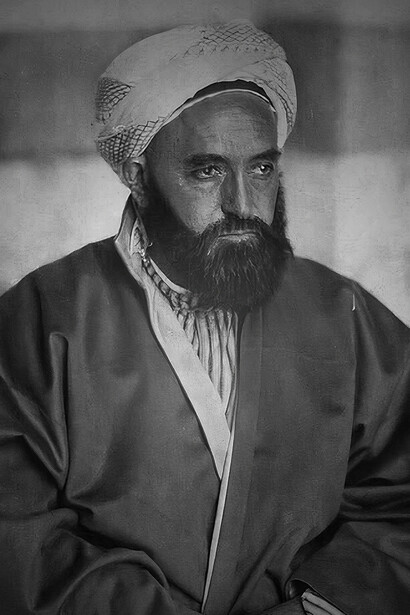

In the early 1830s, a young leader named ‘Abd al-Qadir emerged as one of the principal figures opposing French rule. A religious scholar and political figure, he became central to the resistance. ‘Abd al-Qadir’s leadership transcended mere military opposition; he sought to create an autonomous Algerian state with its own laws and governance, grounded in Islamic principles.1

The role of merchants: the initial seeds of conflict

While ‘Abd al-Qadir is the most well-known figure of resistance, the conflict between the French and the Algerians began long before his rise to power, with the actions of local merchants playing a pivotal role. The initial catalyst for the French invasion was a diplomatic incident in 1827, which involved the French consul, Pierre Deval, and the Jewish merchant houses of Algiers. These merchants were essential to the economy, supplying grain to France and its military.2

The incident, often referred to as the “coup d’éventail”, was a disagreement between the French consul and the dey of Algiers. The consul’s demand for the French flag to be flown above the citadel sparked a diplomatic crisis, and both parties declared war. This event signalled the beginning of a prolonged conflict between the French and the Algerian populace, with the merchants unintentionally playing a central role in the escalation.

The Jewish merchant class, though not politically unified, was tied to the French through trade and economic interests. Their role in supplying goods, especially grain, to the French forces made them crucial players in the unfolding conflict. However, their alignment with the French would have long-term consequences, contributing to the complex social dynamic of the occupation.3

‘Abd al-Qadir’s strategy: unity and resistance

‘Abd al-Qadir’s resistance was based on more than just military force. He understood the complexities of Algeria’s diverse society, which included Arabs, Berbers, Jews, and other groups. His ability to unite these different factions was crucial to his success in organising a broad-based resistance movement.4 This coalition-building reflected not only his strategic acumen but also his commitment to a vision of Algeria that transcended tribal and sectarian divisions.

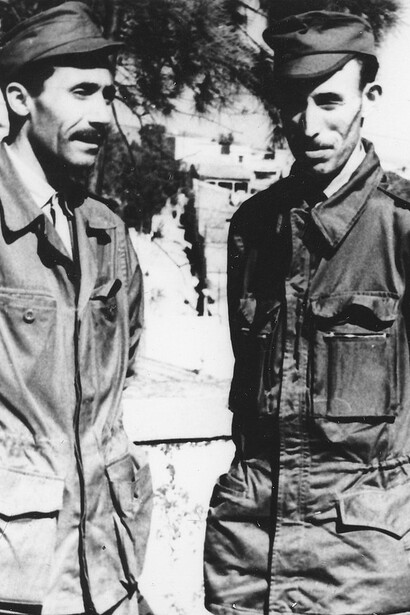

In 1832, ‘Abd al-Qadir established an independent state in western Algeria, which continued to resist French occupation despite the military superiority of the French forces. His strategy was not solely focused on battlefield victories but also on maintaining control over vital territories, using a combination of guerrilla tactics and diplomacy. His forces effectively disrupted French supply lines and military operations for several years, making it difficult for the French to establish full control.5

The Tafna treaty: a temporary peace

By 1837, after several years of conflict, a temporary peace was reached between ‘Abd al-Qadir and the French through the Tafna Treaty. The treaty allowed ‘Abd al-Qadir to retain control over substantial portions of western Algeria and temporarily halted hostilities. For a brief moment, it seemed that a coexistence between the French and ‘Abd al-Qadir’s state might be possible.

However, the Tafna Treaty ultimately failed to bring lasting peace. Both parties had different interpretations of the agreement, and the underlying tensions remained. While the French were willing to negotiate with ‘Abd al-Qadir for strategic reasons, they were ultimately committed to Algeria’s full integration into their empire.6

The shifting dynamics of resistance

As the conflict wore on, ‘Abd al-Qadir faced internal challenges as well. Not all Algerian tribes or leaders supported his vision or leadership. Some sought peace with the French or preferred a more localised form of governance. These divisions complicated ‘Abd al-Qadir’s efforts to unify Algeria under his banner of resistance.

Meanwhile, the French increasingly resorted to brutal tactics, including scorched earth policies, to suppress the resistance. Cities and villages were razed, and civilians were caught in the violence. Despite this, ‘Abd al-Qadir remained a key figure in the resistance until his surrender in 1847.7 His continued presence, even amid growing fractures and intensifying violence, became a symbol of enduring opposition to colonial domination.

The merchants’ role in the resistance and occupation

While ‘Abd al-Qadir’s military efforts are widely recognised, the role of local merchants, especially Jewish merchants, was crucial in shaping the political and economic landscape of colonial Algeria. The merchants had a complex position, often caught between the pressures of the French military and the indigenous Algerian resistance.

In the early years of the occupation, many merchants found themselves navigating the delicate balance of maintaining their trade relations with the French while also preserving their cultural and economic ties to the local population. Some attempted to mediate between the two sides, seeking accommodation, while others sided more directly with the French, in part due to economic interests.8

Nevertheless, as the French extended their control, the merchants, especially those aligned with the French, faced increasing hostility from Algerian resistance groups. The economic ties they held with France became a point of contention, further complicating the dynamics of resistance. The merchants’ trade routes, including the supply of grain and other goods to French forces, were disrupted by the growing conflict, and they were often viewed as collaborators by Algerian resistance leaders.8

‘Abd al-Qadir’s surrender and legacy

By 1847, after years of fighting and a gradual loss of territory, ‘Abd al-Qadir was forced to surrender to the French. His defeat marked the end of the organised resistance in Algeria, but the conflict itself did not end. The French would continue to face sporadic uprisings and resistance from local Algerian leaders, and the lasting effects of the invasion were felt throughout the region for generations.9

‘Abd al-Qadir’s surrender did not erase his significance in Algerian history. He became a symbol of resistance to French colonial rule, but his leadership and the nature of his struggle remain subjects of historical interpretation. While some viewed him as a unifying force, others saw him as a leader unable to fully unite Algeria under a single banner.9 His attempts to balance religious principles with political power, while respecting tribal autonomy, showcased the complexity of the Algerian resistance.

The broader context of French colonisation

The story of ‘Abd al-Qadir is not just a tale of military resistance but part of a broader narrative about French colonialism in Algeria. The French viewed the conquest as necessary for the expansion of their empire, but the impact on Algerian society was profound and long-lasting. The conquest led to the destruction of cities, the displacement of populations, and a reshaping of the region’s social and political structures.

Meanwhile, the role of merchants highlights the multifaceted nature of the occupation. As key figures in the economy, the merchants’ allegiances, whether with the French or the resistance, shaped the early days of colonial Algeria. They were often the intermediaries between French colonial ambitions and the indigenous populations, contributing to the complexity of the conflict.10

While ‘Abd al-Qadir's military efforts were eventually subdued, his resistance remains an important part of Algeria’s struggle for independence. His story highlights the complexities of colonial encounters, where local resistance was not only about military force but also about preserving cultural, religious, and political autonomy.

Conclusion: ‘Abd al-Qadir and the Algerian experience

In reinterpreting the French conquest of Algeria, ‘Abd al-Qadir’s role provides a valuable lens through which we can better understand the dynamics of colonial resistance. His leadership, though ultimately unsuccessful in stopping the French invasion, was crucial in challenging French authority in Algeria.

‘Abd al-Qadir’s legacy is not one of simple victory or defeat. It is a reflection of the broader complexities of colonialism, where power struggles, internal divisions, and the resilience of indigenous populations intersected.

His story, alongside the role of merchants and other local actors, contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the Algerian experience during French colonisation and serves as a reminder of the many voices of resistance that were heard, even if they were not always successful in changing the course of history.

References

1 Asma Rashid, “Emir Abd-al-Qadir and The Algerian Struggle,” Pakistan Horizon 13, no. 2 (1960): 119.

2 James McDougall, “Conquest, Resistance and Accommodation, 1830 - 1911”, in A History of Algeria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 51.

3 Joshua Schreier, “From Mediterranean Merchant to French Civiliser: Jacob Lasry and the Economy of Conquest in Early Colonial Algeria,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 44, no. 4 (2012): 634.

4 July Blalack, “The Migration of Resistance and Solidarity: ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazāʾirī’s Promotion of Hijra,” Mashriq & Mahjar 7, no. 2 (2020): 28.

5 Benjamin Claude Brower, “The Amîr ʿAbd Al-Qâdir and the ‘Good War” in Algeria, 1832-1847,” Studia Islamica 106 (2011): 177, DOI: 10.1163/19585705-12341257.

6 Cheryl B. Welch, “Colonial Violence and The Rhetoric of Evasion: Tocqueville on Algeria,” Political Theory 31, no. 2 (2003): 246.

7 Katherine Bennison, “Dynamics of Rule and Opposition in Nineteenth Century North Africa”, The Journal of North African Studies 1, no. 1 (1996): 13.

8 Joshua Schreier, Jews, Commerce, and Community, 27.

9 Nora Achrati, “Following the Leader: A History and Evolution of the Amir ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi as Symbol,” The Journal of North African Studies 12, no. 2 (2007): 149, 150.

10 Joshua Schreier, “Jews, Commerce, and Community in Early Colonial Algeria,” in Arabs of the Jewish Faith: The Civilising Mission in Colonial Algeria (Rutgers University Press, 2010), 26.