The sociopolitical and technological changes stoked by World War II continue to shape the present moment. It is a moment marked by obsessive, if not hysterical, production and consumption of image and products, intertwined with the ever-evolving conception of individualism. World War II sparked an age of revolution in electronics (cameras, television, phones, computers), in tandem with social revolutions rooted in the concept of individualism and personal rights.

The rise of the image and television in the postwar period was in tandem with the cultural and economic transformation of the U.S. from a New Deal socioeconomic order reliant on labor to a culture of mass consumption dependent on credit in the decades after WWII. The world’s most powerful military promised to keep the lines of trade open so long as the so-called “third world” provided the labor and cheap material needed to enable America’s conspicuous consumption.

By the end of what Time Magazine’s Henry Luce referred to as “The American Century,” the consumer, as opposed to the soldier, had emerged as the most readily recognized subject of history, the allure of mobility and abundance replacing the fascination with firepower. The increased entrenchment of corporate America with Madison Avenue in the half-century after World War II ultimately facilitated the perpetuation of an emerging collective American identity defined by a consumerist culture in which the illusion of individualism could be tangibly purchased via mass-produced goods such as Air Jordan basketball shoes.

The entire trope of what it meant to be American was from 1945 through to the millennia reformed around an ethos of self-identity through consumption. Imagery drove the ethos and made it normative in a sociopolitical climate in which the U.S. was the world’s last superpower left standing after the War.

The 1960s were an especially volatile time in American history. Issues centered on war, race, and “law and order” caused recrimination at a rate previously unseen in the postwar period. Hundreds of cities and towns throughout the U.S. were sources of confrontation and radicalization in a highly complex and interwoven Culture War. “Vietnam was, as Marshall McLuhan once wrote, “lost in the living rooms of America – not on the battlefields of Vietnam.” The horrific images of atrocities taking place daily in Vietnam were beamed into American homes on the nightly news. This undoubtedly helped turn public opinion against the war and strengthened the resolve of anti-war activists. Proponents of the war conversely, claimed that images such as student protesters during the 1968 Democratic National Convention hoisting Viet Cong flags in a Chicago park strengthened the resolve of North Vietnamese enemy combatants.

The conscious first-person abstraction of battle into imagery was evidenced in troops in Vietnam long before the images beamed into American living rooms on the nightly news. “U.S. Marine Corps divisions were willing to engage in battle,” Friedrich Kittler wrote in Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, “only when TV crews from ABC, CBS, and NBC were on location.”

A salient result of the increased and often abstracted use of imagery by grassroots activists and corporate conglomerates alike in the decades during and after the Vietnam War forever and drastically changed the tenor and tone of war coverage. McLuhanites who reflected responsibility towards the media for “losing Vietnam” must be puzzled as to why funneling images of war into American living rooms via simulacrums such as lifelike videogames set in Iraq and Afghanistan can’t seem to help the American military achieve its objectives in the twenty-first century. Unless, of course, the objective is that there simply is a war.

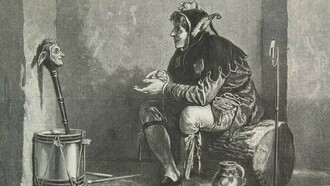

The proliferation of war simulacrums since the end of the Vietnam War provides credence to Thomas Pynchon’s deduction that “real wars are not fought for people or fatherlands, but take place between different media, information technologies, data flows.” The “message and media,” Pynchon noted, “have become one.” Like some mangled snake eating its tail, war and media constantly feed on the same pulse, energy, and phenomenon until it is impossible to tell which is the Golem and which is the doppelganger of the Golem.

Tommy Smith and John Carlos knew that the doppelganger of themselves receiving their Olympic medals projected throughout the world via live television and immortalized on the front covers of newspapers was far more universally powerful than winning the medals. The image of Smith, the 200-meter-sprint gold medal winner at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, and bronze medalist Carlos, with their fists thrust into the night sky, is one of the most iconic and enduring images of the Twentieth Century.

The gold medal race was the moment of a lifetime for most of the runners competing, but for Smith and Carlos, it was merely a prelude to a universal statement projected through still images of themselves beamed throughout the world. Smith and Carlos were both politically active pupils of Harry Edwards, a revolutionary sociologist professor at San Jose State University. Edwards, Smith, and Carlos had a keen understanding of the importance of using the Olympics, one of the few world stages available in 1968, to create a universal statement via a universal medium – the still image.

The iconic image of the runners donning red, white, and blue tracksuits, with medals draped around their necks, and their shiny-black gloved fists hoisted in the clear Mexico City night sky remains a potent symbol of human rights. The image of Smith and Carlos is markedly different from the subjugated, inferior, and mistreated clown depiction imposed on African Americans that was so prevalent throughout the Jim Crow era, the residue of which can still be found in genres of popular musical performance that portray African Americans as hyperviolent and sexually predatory.

Feminists in the decades after the Vietnam War were also acutely cognizant of the deleterious power images of females perpetuated by mass media in the postwar period had had in perpetuating their subjugation and the insidious illusion of inferiority in the half-century after World War II. The skillful and articulate use of the image by feminists became one of the most powerful means with which Women’s Rights activists could disseminate the oppression and plight of women in the United States and throughout the world.

The 1960s were a watershed moment because of the strategic escalations on behalf of a myriad of grassroots organizations, such as the Civil Rights Movement, Women’s Rights Movement, Black Nationalists, Students for a Democratic Society, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and dozens of other activist networks that were just beginning to win hearts and minds on a global scale. But these strategic escalations would be met with strategic escalations in the decades after the Vietnam War.

American wars in the decades after Vietnam were, for example, strategically and conspicuously sanitized from the public by corporate media, which is conglomerated with numerous economic enterprises, including corporations engaged in nation bombing and rebuilding. Yet at the same historical moment, war and mass culture were being ushered into the gaping hearts, minds, and homes of video gamers all around the globe.

By the turn of the century, the censorship of the harsh realities of war grew so pervasively abstracted in American life that images of soldiers’ coffins draped in the American flag were banned from corporate airwaves, but anything that might create the perception of an enemy was highly publicized. There was even a color-coded chart to inform one how hysterical he or she should logically be from one day to the next. This can be viewed as a hysterical strategic escalation by creating the perception of fear juxtaposed with a concerted effort to create the perception of sanitation of war. The whole reality of mass media in the Twenty-First Century has become suffused with a farcical videogame-like alter-reality, as if stifling images of coffins would be akin to hitting the reset button on a video game – as if nobody really died – play again.

The American experience of war has been sanitized for those experiencing it in the blue-white glow of their home television. More peculiarly, war has been sanitized for those engaged in battle, which is more computerized and remote than at any point in human history. Videogames increasingly serve as simulacrums for war; war serves as a simulacrum for videogames.

By the turn of the Twenty-First Century, a dogmatic belief in the free market tinged nearly every image produced and consumed in the U.S. prior to the proliferation of the World Wide Web.

In the lead-up to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, news corporations incessantly reported on weapons of mass destruction and spoke of war as if it were an inevitable part of preserving Americans’ safety and way of life. The so-called expert commentary and images perpetuated by mass media in the months after September 11, 2001, set norms and narratives that guided national policy in the first decade of what neoconservative Warhawks such as Paul Wolfowitz and Donald Rumsfeld referred to as “The New American Century.”

The sanitation of war coverage by corporate conglomerated news outlets, coupled with video games that trained children for war, is a constant reminder that modern media are profoundly suffused with war, and the history of communication technologies can indeed be described as a series of strategic escalations between war mongers and opponents. The issue is that the video games that train children for war also train children to be ambivalent about actual war.

In the new century, Konrad H. Jarausch and Michael Geyer wrote in Shattered Past: Reconstructing German History, “war and mass culture go hand and hand.” The abstracted memory of reality becomes suffused with media so pervasively that images, movies, the news, and videogames are so deeply enmeshed that reality and dis-reality grow increasingly, if not exceedingly, entwined, complicated, and convoluted. “Computerized weapons systems are more demanding than automated ones,” Friedrich Kittler wrote in Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. “If joysticks of Atari video games make children illiterate, President Reagan welcomed them for just that reason: as a training ground for future bomber pilots.”

Kittler’s argument seems more apt than ever, considering 9/11 and the decades that followed. Lower Manhattan was, for example, the scene of one of the most memorable and powerful images in human history. The supposed masterminds of the tragedy sent videotapes of themselves claiming mass murder to media outlets all around the globe. These videos were apparently shot in remote caves somewhere in the “Developing World,” yet were published universally. In fact, many of those who watched 9/11 unfold in real-time wondered if they were watching a production rather than a terrorist attack. The harsh reality is that the attack was a production made for television, and it exists forever on the World Wide Web.