I. A country trapped at a breaking point

By the end of 2025, Venezuela will be hemmed in by its own ruins and by an international environment that has stopped tolerating the criminal experiment that governs it. This is not a “new phase” of the crisis; it is the stage where internal exhaustion coincides with a reshaping of the balance of power in the Caribbean.

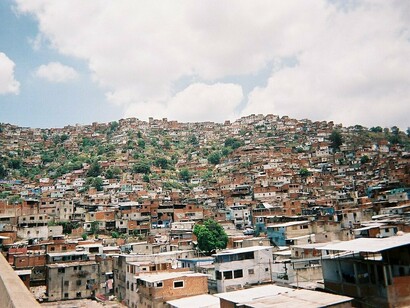

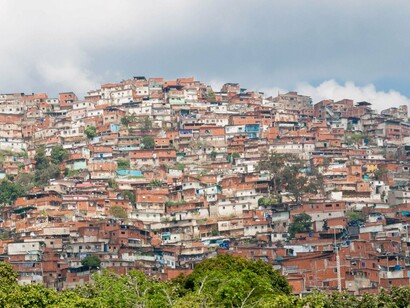

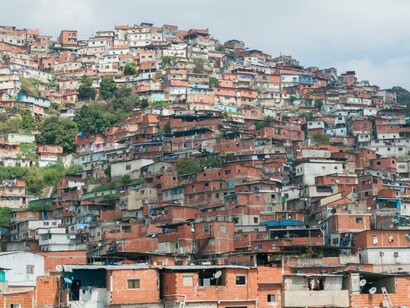

Internally, the country reaches this limit with three structural features that can no longer be concealed. An institutional crisis in a terminal state: captured public powers, a total absence of credible arbiters, and legality turned into an instrument of selective repression. An economy reduced to enclaves of rent extraction and crime, with no capacity to generate basic well-being or any horizon of social mobility. And an irreversible social fracture: more than eight million Venezuelans have left the country since 2014, turning Venezuela into one of the largest displacement crises on the planet, with most migrants and refugees scattered across Latin America and the Caribbean.

At the same time, the regime no longer even tries to simulate normality. The power apparatus rests on a mix of coercion, illicit economies, purchased loyalties, and external protection. Official discourse continues to talk about a “blockade” and an “economic war”, but the deliberate destruction of institutions and markets is an internal decision, not an exogenous imposition. Sanctions raise transaction costs, but they do not explain the criminalization of the state or the systematic emptying of the country.

It is the external environment that turns this prolonged crisis into a turning point. Since August 2025, the United States has carried out the largest military deployment in the Caribbean in decades, under the banner of the so‑called war against the cartels and Operation Southern Spear. What began as an increase in naval assets for drug interdiction quickly evolved into a device of strategic pressure on the Venezuelan regime.

In a few months, the usual presence of “two or three” U.S. ships in the southern Caribbean was replaced by a full strike group: guided‑missile destroyers, an amphibious ship with thousands of Marines, an attack submarine and, since November, even the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford with its full air wing, raising the total contingent to around 15,000 troops between the Caribbean Sea and Puerto Rico. Historians and analysts describe this deployment as the largest in the region since operations in Haiti in the 1990s.

Since September, the campaign has included airstrikes against boats the United States presents as drug‑trafficking vessels operated by Venezuelan groups and their allies. At least twenty such attacks have been publicly acknowledged, with dozens of deaths, in what U.S. media describe as the first series of kinetic actions of this kind in the hemisphere since Panama in 1989.

From the regime’s perspective, all this is presented as imperialist aggression. From the perspective of any cold observer, the picture is different: a state already devastated internally, governed by a criminal structure with regional projection, now facing an international environment in which its ability to operate with impunity has been drastically reduced. The Maduro regime now operates with a much narrower political, financial, logistical, and territorial margin than it did five years ago.

II. The mirage of new US-Venezuela talks

As ships and uniforms multiply in the Caribbean, a familiar diplomatic language reappears on the surface: “back channels”, “windows for diplomacy”, “a chance for a new start with Caracas”. Recently, President Donald Trump has said he is willing to talk to Maduro even after designating him as the head of a terrorist organization, following the classic formula: if it can be done “the easy way, fine; if not, the hard way”.

Within that frame, Washington once again imagines the same script: combining the stick and the carrot—military and financial pressure on one side, the promise of relief if Caracas offers concessions on drugs, migration, or energy. Influential think tanks describe that dilemma precisely: using the power of sanctions to extract gradual changes—some control over cocaine flows, a bit of electoral window dressing, more migrants accepted back, or shifting toward a new phase of “maximum pressure” to force a rupture within the Maduro elite. In that narrative, a possible “Trump–Maduro dialogue” would be the master move that resets the board in exchange for a calibrated package of concessions and energy licenses.

The problem is not tactical, but conceptual. These new conversations are built on two original errors. First, they assume that Maduro decides, when in reality he executes a power design he does not control, anchored in intelligence services, military structures, and organized crime networks that answer to another hierarchy. Second, they treat Venezuela as a conventional dictatorship with negotiable incentives, when in fact it operates as a hybrid criminal system, externally tutored, whose primary logic is the protection of illicit rents, not the management of a state.

Under those assumptions, every new round of talks reproduces the same script from recent years: the regime concedes the bare minimum needed to ease sanctions, recover cash flows, or divide the opposition, buys time, and, once stabilized, breaks whatever it signed. That is exactly what happened with the Mexico and Barbados rounds, where electoral commitments served to obtain oil relief that was later reversed due to non‑compliance. It is not an accidental failure of “dialogue”; it is the natural consequence of negotiating with the wrong actor and under a misdiagnosis of the problem.

III. Returning to Evilness Cahoot: the anatomy of the regime

If the Washington–Caracas conversations are a mirage, it is because they continue to describe the Maduro regime as something it no longer is: a negotiable authoritarian government. Evilness Cahoot (Contubernio Maligno in Spanish), published in 2022, starts from a different premise: Nicolás Maduro rises to power through a cold coup d’état, wrapped in a veneer of legality and orchestrated from Havana, and since then, he has ruled as the head of a tutored criminal structure.

The book reconstructs the 2012–2013 sequence as a process of sustained constitutional rupture: Chávez’s transfer to Cuba, absolute opacity regarding his real condition, the refusal to apply the succession rules laid out in the Constitution, and the use of the Supreme Court to prolong a government without a sitting president and later install Maduro as “president” without a direct mandate, allowing him to run for office without stepping down. These are not isolated anomalies, but a coup d’état under judicial cover that turns Maduro into a usurper from day one and remains so to this day. It is no coincidence that the United States does not recognize Nicolás Maduro as the legitimate president of Venezuela; this position confirms, at the diplomatic level, what the book laid out in constitutional terms.

The second central element is Cuba’s hand behind power. Evilness Cahoot shows that the dictatorship does not “drift” toward Cuba; it is born and existentially supported by the Cuban tyranny. From the outset, security, counterintelligence, the chain of command, and information management are designed in a shared “war room” with Cuban officers acting as the regime’s auxiliary brain: they set objectives, calibrate repression, monitor the opposition, and keep Venezuelan officers under watch. Subsequent investigations confirmed this architecture: secret agreements dating back to 2008 allowed Cuba to reconfigure Venezuelan military intelligence, establish a capillary surveillance system, and shield the regime against internal dissent.

Within that framework, the book does not describe the Maduro system as a government, but as a criminal organization of state, structured around five permanent lines of action: systematic persecution of dissidents; massive social precarization as a mechanism of control; organized violence through FAES, SEBIN, DGCIM, and colectivos; functional integration with organized crime networks and foreign armed actors; and the forced expulsion of millions of Venezuelans to manipulate the electoral map and vacuum internal pressure out of the country. That design matches point by point what is now being examined by the International Criminal Court and organizations such as Human Rights Watch under the category of crimes against humanity.

The third element is political‑strategic. The publication of Evilness Cahoot in 2023 narrows the regime’s room for maneuver because it sets an interpretive framework that can no longer be reversed. For years, the Maduro system survived by playing with ambiguity: presenting itself to some as an “authoritarian government with human‑rights problems” and to others as a “victim of sanctions”. The book methodically organizes, with evidence, what many actors only perceived in fragments: this is a transnational criminal project, directed from Cuba, that uses the Venezuelan state as a platform for internal repression, illicit business, and regional intervention.

The events of 2025 dramatically confirm what Evilness Cahoot had already laid out: the regime’s structure has been fully institutionalized as a platform for transnational crime. In July, the Cartel of the Suns—the network linking high‑ranking military and state officials to drug‑trafficking activities—was officially designated by the United States as a terrorist organization, in parallel with the designation of the Tren de Aragua as a transnational criminal organization. That double classification not only gives legal weight to longstanding accusations against the regime as a sponsor of illicit economies and exported violence; it also turns into operational fact what had previously been confined to reports and dossiers: the Venezuelan regime functions as a criminal consortium with active networks beyond its borders. The immediate consequence is a drastic reduction of its international room for maneuver and the direct exposure of its leadership—including Maduro—to criminal, financial, and potentially military action.

In other words, the cahoot, the contubernio, has been named and described. Once it is accepted that Maduro emerges from a Cuba-tutored coup and that the regime operates as a criminal consortium, the system can no longer be read as a negotiable authoritarian government but as a criminal project under tutelage. At the center of that project lies an actor the international conversation still prefers not to name clearly: Cuba.

IV. The permanent blind spot: Cuba

There is a fact almost all international actors know but prefer not to name: strategic decisions about Venezuela are not made in Miraflores; they are made in Havana. Maduro manages; Cuba decides. That is the blind spot that distorts everything else.

Since at least the mid‑2000s, Cuban involvement has gone far beyond doctors and sports trainers. Havana reshaped Venezuela’s intelligence and counterintelligence architecture, advised the transformation of DGCIM into an apparatus devoted to spying on its own armed forces, and placed its cadres in key nodes of the command structure. What Evilness Cahoot described as a joint “war room” is today a consolidated structure: CESPPA, DGCIM, SEBIN, and the Presidency operate in a closed circuit with Cuban officers who monitor, recommend, and veto.

This is not horizontal cooperation; it is functional penetration. Without that backbone of Cuban cadres—analysts, instructors, liaison officers, technical operators—the regime would have had a far harder time crushing military dissent, anticipating internal fractures, and sustaining the structure of fear that keeps it in place.

The underlying reason is simple and brutal. For the Cuban elite, Venezuela stopped being an ally and became a strategic resource. Ever since the Petrocaribe era, Venezuelan oil has been the lifeline of the Cuban economy. Even with recent cuts in supply, every adjustment in the flow of crude and fuel from PDVSA is felt immediately on the island in the form of blackouts, rationing, and emergency measures. Havana cannot afford to lose that energy lung without facing a new “special period” under geostrategic conditions far worse than those of the 1990s.

That is why the relationship is hierarchical, not symmetrical. Venezuela provides oil, foreign currency, gold, and a geopolitical platform; Cuba provides the know‑how of total control: intelligence, counterintelligence, repression manuals, information management, propaganda training, and a tested apparatus of “political guidance” over the armed forces. Various analysts have described this outcome as one of the greatest geostrategic successes of Cuban intelligence: projecting power far beyond its economic capacity by capturing decision‑making in a much larger and more resource‑rich country.

That is what this text calls a “cold occupying power”. There are no Cuban tanks in the streets of Caracas, but there is a de facto occupation of the systems that decide who lives, who rules, who goes to prison, and who loses power. Within that scheme, Maduro cannot accept any arrangement that contradicts Havana’s red lines—not in political opening, not in the structure of the armed forces, and especially not in the web of illicit economies that now sustain both regimes.

The operational conclusion is straightforward: no negotiation with Maduro can alter what Cuba needs to preserve. On the contrary, any “dialogue” that ignores the centrality of the Cuban factor serves only to buy time for Havana. As long as the Venezuelan conflict continues to be read as a dispute between “government” and “opposition” within Venezuelan borders, the real decision‑maker—the Cuban power apparatus—will remain off the table and therefore beyond the reach of any agreement.

Since Cuba is the real center of decision-making, the only serious transition logic is the one set out in When the People Rise: one does not negotiate with spokesmen, but with those who control the actual instruments of force.

V. When the people rise: how a real transition is negotiated

When the People Rise, published in August 2024—after Edmundo González’s victory in the July elections and the subsequent fraud committed by Nicolás Maduro’s regime—sets out an operational principle that is essential for understanding why hemispheric policy has repeatedly failed in Venezuela: in a transition process, one does not negotiate with spokesmen, but with those who control the actual instruments of force.

That principle helps explain the serial failure of Oslo, the Dominican Republic, Barbados, and Mexico, all of which treated Miraflores as the natural interlocutor and Nicolás Maduro as the decision-maker, against the evidence of who actually controls the instruments of force.

The book demonstrates that the critical centers of power—intelligence, counterintelligence, the military structure, control doctrines, repression, strategic communications—were integrated years ago into the Cuban circuit. That functional transfer implies an incontrovertible fact: no strategic decision about democratic transition in Venezuela can be made without Cuba’s approval.

Dialogue processes promoted by the international community have systematically ignored this structural element. They have focused on negotiating symptoms—electoral conditions, sanctions, timelines, limited releases of political prisoners—while the main cause remained intact: Cuban tutelage over the apparatus that guarantees the regime’s continuity. Negotiating with an executor rather than with the decision‑maker has always produced the same result: stalling, attrition, and setbacks.

The logic is direct. Cuba depends on Venezuela for its economic and geopolitical survival; the Venezuelan regime depends on Cuba for its operational survival; no transition is viable without altering that equation. That is why When the People Rise argues that any realistic transition strategy must treat Cuba as an essential interlocutor. This is not about granting legitimacy, but about recognizing a geopolitical fact: the actor that sustains the system is the only one that can dismantle it.

As long as that node is not addressed clearly, any attempt at dialogue will remain a ritual of repetition: new rounds, new facilitators, new promises—and the same outcome. Not because there is no will, but because there is no rigor in identifying the real decision‑maker. The Venezuelan transition, therefore, demands a strategic reorientation: abandoning the mirage of negotiating with Maduro and turning attention to the true axis of power that has determined Venezuela’s political fate since 2012.

VI. The cardinal error: negotiating with Maduro

The Oracle of the Great Mamerto, published in 2024, takes to its extreme a theme that runs through this entire text: the regime is not just wounded; it is defeated, and its defeat is irreversible. The book describes, in the form of chronicle and allegory, the path from palace superstitions to the moment when Nicolás Maduro’s defeat becomes visible on his own face, “like the mark of Cain”, after Edmundo González’s victory on July 28, 2024, and the fraud that followed that election. From that point on, the regime is no longer fighting to win, but to postpone the inevitable.

The book does more than document the decline; it explains its nature. Its narrative axis is the figure of “the Great Mamerto”, the nickname used behind Maduro’s back by the Cuban elite. The term, taken from a Cuban children’s toy similar to Mr. Potato Head—a hollow plastic head whose parts can be rearranged at will—encapsulates the central political thesis: Maduro is a constructed, replaceable, interchangeable figure. He is not a leader; he is a useful artifact. Real power lies elsewhere.

The episodes recounted in The Oracle of the Great Mamerto—Cuban intervention in strategic decisions, military purges dictated from Havana, obsessive fear of internal betrayal, desperate consultations with shamans, babalawos, astrologers, Hindu monks, and evangelical pastors—portray a man who no longer governs the regime, but his own panic. The chain of signals is coherent: the “Mamerto” label coined in Cuba; the realization that intelligence, counterintelligence, and the system’s survival depend on another command; the intimate acknowledgment, within the inner circle, that on July 28, 2024, the regime was electorally defeated and that everything that followed was the management of fraud and of the fall.

In that context, the status of a puppet is not a moral category, but a technical one. Maduro does not decide the design of repression; he does not define the relationship with Cuba; he does not control the criminal equation that sustains the regime; and in the final stretch, he does not even decide his own political fate. The major decisions—the purges, the sacrifice of figures such as Tareck El Aissami, the red lines of any negotiation—are set from outside: by Havana, by the criminal network that shares profits with the ruling clique, by a circle that already contemplates his replacement. Maduro is the visible face of a will that is not his.

That is why negotiating with him is not just a futile gesture, but a cardinal error of strategic design. He is a player in a phase of irreversible defeat, with no control over the real levers of power, no capacity to guarantee implementation, and no political future of his own. Any commitment signed with Maduro is doubly dead: from above, because it requires Havana’s green light; from below, because it rests on a leadership that the book itself portrays as in retreat, surrounded by omens, defections, and survival calculations among its allies.

If Evilness Cahoot stripped the regime of its criminal and tutored character, The Oracle of the Great Mamerto depicts the moment of its break: a defeated system, sustained by inertia, administered by a puppet despised by his own patrons and considered expendable. Under such conditions, insisting on negotiating with Maduro is not just naïve; it is insisting on bargaining with a mask. And no serious transition can be built by talking to the mask instead of confronting the power that holds it in place.

The irreversible end

Everything laid out above leads to an essential statement. Evilness Cahoot is the book that dismantled the regime’s criminal architecture, and subsequent events have brought it to its current breaking point by revealing, with precision, its true nature and external dependencies. From that X‑ray on, the regime can no longer be interpreted as a conventional dictatorship; it appears for what it is: a criminal project under tutelage, designed and sustained from abroad.

Taken together, the works analyzed here explain why any dialogue with Maduro’s regime is structurally misguided. The error does not lie in talking; it lies in failing to identify who actually decides. The liberation of Venezuela requires, before any transition blueprint, naming an inescapable fact: the Venezuelan regime is a Cuban project.

Within that frame, Nicolás Maduro’s fate is sealed. The choice between stepping down or facing a forced end—whether through the combined pressure of democratic insurgency and operations such as Southern Spear—will not be resolved by talking to him.

It will be decided, as all strategic decisions have been since 2012, in Havana.