On a misty morning in Kericho, Kenya’s famed tea capital, workers bend low over endless rows of green bushes. “We harvest for the world,” says 36-year-old picker Alice Chepng’etich, her hands moving swiftly. “But many of us go home without enough maize flour for ugali."

It is a paradox that defines African agriculture: vast exports of tea, coffee, cocoa, tobacco, and flowers to Europe and beyond, yet growing dependency on imported food to feed local populations. The roots of this contradiction stretch back to colonial rule, when European powers reorganized Africa’s farms to serve imperial markets rather than local needs.

Seeds of empire: how colonial powers reshaped agriculture

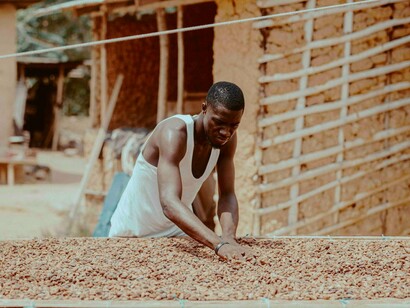

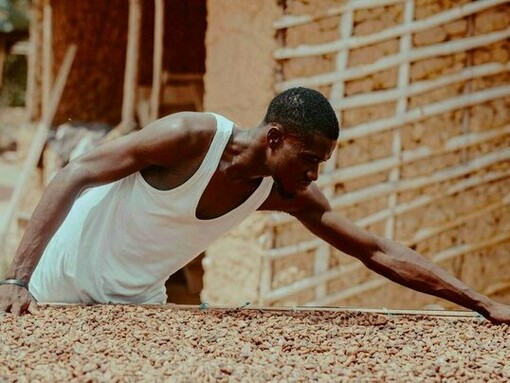

Colonial administrators saw Africa as a plantation. In Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, farmers were compelled to grow cocoa for Europe’s chocolate industry. “Our grandparents were punished if they planted cassava or yams instead of cocoa,” recalls Kofi Mensah, a farmer from the Ashanti region. “The hunger that followed was the beginning of our troubles.”

In East Africa, coffee and tea took over the highlands. British settlers in Kenya seized fertile land in Kericho and Nyeri, pushing Africans to rocky outcrops and forcing them into wage labour. In Southern Africa, vast tobacco estates emerged in Zimbabwe and Malawi, while cotton fields spread across Sudan and Egypt to feed British textile mills.

Even flowers, now a major export from Kenya and Ethiopia, grew out of colonial legacies of serving foreign tastes. “We had the water, they had the demand. So we grew what they wanted,” says an Ethiopian horticulture worker, pointing at flower farms near Lake Ziway.

Fragile economic inheritance

Decades later, this export-first model remains largely intact. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire still derive over 60% of export revenues from cocoa. Kenya is the world’s largest black tea exporter. Zimbabwe and Malawi depend heavily on tobacco, and Ethiopia’s economy leans on coffee, but global commodity markets are fickle. A price slump in cocoa or coffee can decimate farmers’ incomes. “When cocoa prices fall, our entire village feels it,” says Mensah. “School fees, food, even medicine—we cannot afford them.”

Meanwhile, Africa’s food import bill continues to climb. Nigeria, once famed for Kano’s groundnut pyramids, now imports millions of tons of rice and wheat annually. Ethiopia, despite coffee riches, regularly appeals for international food aid during droughts. Dr. Jane Njoroge, an agricultural economist at the University of Nairobi, notes:

The colonial model created a structural trap. Export crops bring foreign exchange, but they leave African nations exposed to global shocks. Local food systems were neglected, and we are still paying that price.

Food security traded away

The side-lining of indigenous crops—sorghum, millet, cassava, and African leafy vegetables—has weakened resilience to climate change. These crops, hardy in drought, were replaced by export-focused monocultures.

“Maize is not even our traditional food here,” says Ruth Atieno, a farmer in Siaya County, western Kenya. “But we depend on it now, and when the rains fail, we go hungry.”

The irony is cruel: while tea and flowers from Kenya line supermarket shelves in London, Nairobi residents queue for maize flour.

Railways, roads, and the colonial map

The very infrastructure that defines modern African states was designed to serve exports. The Kenya–Uganda railway was built to move coffee and tea to Mombasa. In West Africa, cocoa rail lines led straight to coastal ports. In Southern Africa, rail networks moved cotton and tobacco toward Europe.

“Colonial infrastructure was about extraction, not connection,” says historian Dr. Samuel Dlamini in Harare. “Even today, it is easier to send coffee from Addis Ababa to Europe than maize from Ethiopia to Kenya.”

The weight of the past in the 21st century

The colonial legacy endures not only in economics but also in food sovereignty. Many African countries remain bound to cash crops, while millions rely on imported staples. Climate change, fertilizer shortages, and global market swings deepen the crisis.

Yet signs of resistance are emerging. Ghana is investing in cassava and poultry to ease cocoa dependency. Kenya is promoting indigenous vegetables and drought-resistant maize varieties alongside its tea exports. Ethiopia is diversifying into pulses and cereals. Farmers’ cooperatives in Malawi are encouraging smallholders to balance tobacco cultivation with food crops like groundnuts and sweet potatoes.

“We cannot eat tobacco,” says Malawian farmer Joseph Banda with a wry smile. “So I plant groundnuts next to my tobacco. The market may want one, but my children need the other.”

Toward food sovereignty

The lesson of crop colonialism is clear: prioritizing exports at the expense of local food has created fragile economies and hungry populations. To move forward, African countries must rebalance—investing in local agriculture, rethinking infrastructure, and reviving indigenous food systems.

Dr. Njoroge puts it bluntly:

Food security is national security. Africa cannot depend on global markets to feed its people. Our resilience lies in reclaiming crops and systems that colonialism took from us.

The story of Africa’s agriculture has long been written in cocoa pods, tea leaves, and tobacco bales. But its future may yet be secured in cassava fields, millet farms, and resilient local food systems that put African mouths first.

Africa’s top export crops

Ghana & Côte d’Ivoire – Cocoa (over 60% of export revenue).

Kenya – Tea and Cut Flowers (largest foreign exchange earners).

Ethiopia – Coffee (backbone of the economy).

Zimbabwe & Malawi – Tobacco (key export crop).

Nigeria – Cotton and Groundnuts (historic cash crops, now declining).

Kenya leads the way

In a ruling with implications for seed sovereignty movements worldwide, Kenya’s High Court struck down sections of a national seed law that criminalised the saving and sharing of indigenous seeds—a practise relied on by millions of smallholder farmers across Africa.

Justice Rhoda Rutto declared key provisions of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act (2012) unconstitutional, noting that the law’s harsh penalties—including fines of up to US$7,700 and potential jail terms—violated fundamental rights to food, culture, livelihood, and equality. The court also invalidated state powers that had allowed officials to raid community seed banks and seize locally preserved varieties.

The decision is expected to significantly reshape agricultural policy in Kenya, a regional food-production hub. By recognising farmer-managed seed systems as lawful, the ruling compels regulators to move away from punitive enforcement and toward policies that support both commercial and indigenous seed pathways—a shift closely watched by governments and advocacy groups across the Global South.

For farmers, the impact is immediate. Kenya’s smallholders—who produce most of the country’s food and source over 80 per cent of their seeds from informal networks—can now legally save, exchange, and sell traditional varieties. Analysts say this could reduce input costs, bolster climate resilience, and help preserve genetic diversity at a time when extreme weather is threatening crop productivity globally.

“This ruling honours generations of knowledge and ensures future generations can farm without fear,” said petitioner Samuel Wathome. Greenpeace Africa’s Elizabeth Atieno called it “a victory for our culture, our resilience, and our future.” Lawyer Wambugu Wanjohi of the Law Society of Kenya noted that the invalidated clauses had disproportionately favoured large commercial seed companies.

As countries debate how to balance intellectual property rights with food security and indigenous knowledge, Kenya’s ruling is likely to set a precedent—and could influence seed policy reforms across Africa and beyond.