There are moments in history when a civilization no longer knows how to name what it has forgotten.

Today, we live in such a moment.

It is not reason that has collapsed, nor technology that has failed. It is not even morality that has disappeared. What has dissolved is subtler and far more decisive: our shared capacity to affirm becoming as a value in itself.

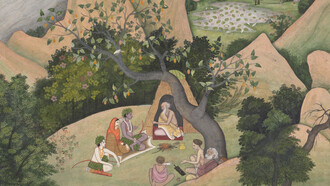

In recent years, I’ve written extensively on what I call Sapiopoiesis—the structural unfolding of subject autonomy under conditions of complexity. But the necessity of this concept became even more vivid to me during a recent visit to the Arp Museum near Bonn. The exhibition explored Romanticism not as nostalgic aestheticism but as a radical utopian current: a longing that never ceased but kept mutating, resurfacing, and demanding new forms. And yet—despite all the critical apparatus—the very word that stood behind it all remained unspeakable: longing.

The untranslatable.

The unmeasurable.

The unmarketable.

It struck me then that we are not just suffering a crisis of values. We are enduring a war against the right to long—to desire something without a predefined form or utility, to grow into one’s own singularity without coercion or formatting.

Philosophy is really homesickness—the urge to be at home everywhere.

(Novalis)

Longing, in this context, functions similarly to what Ernst Bloch (1959) called the Not-Yet-Conscious—a latent capacity for transformative imagination that refuses containment within the present. Likewise, Michel Foucault’s (1971) notion of heterotopias—real spaces of otherness—may be read as spatial correlates of longing’s temporal disobedience. One might also invoke Hans Jonas’s (1979) ethics of responsibility, which roots moral action in anticipatory care for the vulnerable unknown.

What the Romantics intuited—against the grain of an encroaching mechanical rationalism—was that truth cannot be reached by deduction alone, but must be lived through orientation. Today, this insight returns not as nostalgia, but as structural necessity.

The problem is not what we do to animals. It’s what we forget about ourselves

Let me state this carefully and with full respect for legal and ethical clarity:

Recent visual campaigns by certain animal rights groups—however well-intentioned in their critique of industrial animal exploitation—have crossed an epistemically precarious line. In attempting to provoke empathy, they employ imagery that reduces the human being to a symbol of collective guilt. Ethical urgency slides into ontological negation.

This is not a rejection of animal welfare. It is a critique of messaging that unknowingly weaponizes guilt against the very conditions of ethical discernment. When humanity is framed primarily as a species of perpetrators—without distinction between systemic machinery and autonomous personhood—we do not uplift animals. We degrade human moral agency.

Here we must recall Hannah Arendt’s warning (1958) that the collapse of action into behaviour and responsibility into statistical guilt is one of the earliest signs of totalitarian thinking. Ethical clarity begins where structural differentiation is preserved, not abolished.

There can be no real ethics without the structural protection of human subjectivity. We do not defend life by collapsing distinctions that allow us to generate meaning. Nor do we build civilizational coherence by reducing the human to an object of shame.

Why the real crisis is the erasure of orientation

Much of the current discourse on artificial intelligence, ecological collapse, and systemic injustice proceeds with urgency but without interior structure. We design tools and reforms without asking, what must remain structurally intact for any solution to matter?

The answer is not "human nature" or cultural identity. It is the structural right to become: to emerge as a morally situated, sense-making subject under uncertainty.

This echoes the concerns raised by Bernard Stiegler (2016), who warned of the growing "symbolic misery" resulting from the automation of memory, perception, and desire. When knowledge is reduced to function, orientation collapses into control.

Sapiopoiesis is not a theory. It is a name for the minimal condition of civilizational viability: the capacity of individuals to generate moral worlds, not through behavioral compliance or cognitive output, but through sovereign orientation.

When this capacity is substituted with optimization, formatting, or programmatic regulation, even the best-intentioned causes risk becoming counterproductive. We begin to manage reality instead of enabling it.

Simone Weil’s (1943) reflections on affliction and attentiveness also come to mind. Ethics begins not in action but in the preservation of interior space—a space where perception is not overwhelmed by ideological framing.

Longing is not sentiment. It is civilizational intelligence

Romanticism, when rightly understood, was never about escape or nostalgia. It was about refusing to accept that all reality must be already known, measured, or useful.

Longing—true existential longing—is not an indulgence. It is a cognitive refusal of closure. A radical form of noncompliance with world-reduction.

What cannot be optimized, monetized, or pre-defined still matters. And longing is the trace of that mattering.

Longing, in this sense, is not wishful thinking. It is structurally prior to intention—an ontological momentum toward what has not yet been authorized to exist.

This insight is not psychological. It is epistemological. Longing resists the symbolic compression of possibility. It keeps orientation open where systems seek closure.

In this sense, longing functions as a counter-epistemology—a living remainder of the unsystematized that resists algorithmic finality. As Byung-Chul Han (2017) notes in his critique of digital transparency, a world without opacity is a world without eros, and ultimately, without vitality.

One might also turn to Emmanuel Levinas (1961), whose ethics of the face highlights the irreducibility of the Other. Longing, in its highest form, is not a projection but a readiness to respond to what exceeds comprehension.

Toward a post-technocratic ethic of differentiated care

What we face is not a conflict between humans and animals or between humanity and AI. It is a conflict between flattening and becoming.

The ethical question is not whether we care. It is whether our care sustains the structural conditions under which entities—human or non-human—can emerge without being assimilated.

We need a new ethic. Not one based on moral outrage or purity, but on the architectural defense of difference. An ethic of post-symbolic viability.

To care for animals, we must remain morally intelligent.

To survive technology, we must remain epistemically sovereign.

To navigate the future, we must protect the architecture of open-ended becoming.

This is not ideology. It is not a critique. It is the structural work of civilizational design—or, in the words of Gilbert Simondon (1958), a design that preserves individuation as the generative tension between system and emergence.

Even Franz Rosenzweig’s (1921) notion of revelation as dialogic unfolding reminds us: truth does not descend as a system—it emerges through differentiated relation.

To remember longing is not to look back but to clear the path forward, where the subject is not optimized but allowed to become.

Many of the ideas explored here resonate with thinkers across time who have defended becoming, longing, and ethical differentiation against the pressures of systematization. Ernst Bloch’s Principle of Hope and Hannah Arendt’s reflections on natality and moral responsibility help frame the anticipatory dimensions of longing and action. Simone Weil's meditations on affliction and attentiveness remind us that ethical orientation begins with interior depth, while Emmanuel Levinas and Franz Rosenzweig offer relational philosophies that preserve alterity without flattening it.

In more contemporary terms, Bernard Stiegler’s warning about symbolic misery, Byung-Chul Han’s critique of digital transparency, and Gilbert Simondon’s philosophy of individuation all illuminate the epistemic fragility of the self under technocratic compression. Alongside these, Michel Foucault’s notion of heterotopias, Hans Jonas’s anticipatory ethics, and Erich Fromm’s utopian psychology continue to shape the architecture of what I have called Sapiopoiesis and Sapiocratic Design—a civilizational commitment not to system, but to the right to become.