History is not made by necessity, but by the human capacity to begin something new.

(The human condition, 1958, Hannah Arendt)

There are paradises that are not lost through forgetfulness, but because they were taken away. Others vanish into the depths of modern experience. The notion of a lost paradise, understood not as a place to which one can return but as a condition of productive absence, runs paradigmatically through both the poetics of Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) and the artistic practice of Kader Attia (Dugny, France, 1970). In Les fleurs du mal (1857), Baudelaire evokes an Eden dissipated in the smoke of the modern city, where redemption has been replaced by the aesthetic search for the wound.

His worldview is permeated by spleen, that structural melancholy that finds in decay a form of beauty. Rather than deny the fall, he turns it into poetic material. Kader Attia, from another realm, picks up this sensitivity to fracture and translates it into a politics of repair. Confronted with the wounds of colonialism and the dominant narratives of modernity, Attia does not attempt to restore a lost wholeness but makes the fracture visible—sometimes literally highlighting it with gold, as in the practice of kintsugi. For him, paradise has not been lost: it has been stripped away and must be resisted and re-signified through memory and repair. If Baudelaire locates the fall in the modern soul, Attia places it in global history and in the bodies marked by it. Between the two, an aesthetic of the wound emerges, where paradise is not a myth of origin but a symbolic space reshaped by loss, resilience, and critique.

Attia’s work is grounded in an expanded conception of memory: a living archive, woven from fractures, omissions, and uneven sedimentations. His practice activates a contested memory, shaped by colonial trauma, diaspora, and multiple forms of resistance and reappropriation. This sensibility finds a deep resonance in Baudelairean poetry, through its vision of modernity as ruin and decomposition. In Le spleen de Paris (1869), beauty emerges from remains, from the ephemeral and the decadent. “The shape of a city changes more quickly, alas, than the human heart,” he writes, alluding to the instability of the present and the flight of meaning. From another poetic and philosophical horizon, Édouard Glissant (1928–2011) proposes a rhizomatic view of history and identity, where “relation is poetic, or it is nothing” (Poétique de la relation, 1990). For Glissant, memory gains strength by embracing opacity, diversity, and irreducibility. In dialogue with this poetics of relation, Attia develops an aesthetic of the archive as a field of tensions and rewritings, where displaced images and bodies generate new constellations of meaning. In his practice, history appears as a plural montage—a fertile territory for repair and thinking from the fragment.

Every wound leaves a form—a line, an absence, a memory embodied in matter. For Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), the human condition is defined by action, birth, and the capacity to respond creatively to damage. In her thought, the wound represents a threshold from which it becomes possible to act, to speak, to coexist. This vision resonates in the work of Attia, where the wound assumes visual, corporeal, and symbolic form. The suture is clearly visible: each fracture becomes an active surface of thought. Attia works with what is broken—objects, bodies, narratives—and presents them as material available for memory, as intense presence that demands attention. The wound, in this gesture, affirms itself as a space of meaning, as a living trace of a story in transformation.

For Attia, repair is not about erasing that mark, but about working with it, inhabiting it, listening to what it has to say. “On ne peut pas penser réparation sans penser blessure,” ( “One cannot think of repair without thinking of the wound”) the artist asserts, reminding us that every act of repair arises from a wound that persists. His reflection goes beyond the plastic gesture: it interrogates the very root of the word “repair,” inherited from the Latin reparare, meaning “to return to an original state”—an idea deeply embedded in modern Western logic.

But as the artist notes, in many non-Western languages and worldviews, to repair means not to return but to transform; not to close, but to continue with the scar as a sign. Within this distinction lies an ethics and an aesthetics of care, of memory, and of history. Paul Valéry (1871–1945), in the aftermath of the First World War, already intuited the structural fragility of European civilization when he wrote: “We civilizations now know that we are mortal” (Regards sur le monde actuel, 1945). While Valéry contemplates this collapse with lucid melancholy, Attia reconfigures its fragments with an active gesture, making of art a space where what is broken is not concealed, but displayed—as a form of resistance, of transmission, and of meaning.

“The miracle that saves the world… is the fact of birth,” writes Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) in The human condition (1958), referring to the human capacity to begin again. Attia’s work embodies that miracle as a form of ongoing repair—a practice that unfolds from the wound to activate forms of continuity. This repair resembles a lucid surgery: it intervenes in the fracture without sealing it, accompanies memory without fixing it, and transforms the mark into thought. Each gesture materializes a form of listening, a presence that attends to what endures. The wound, in this light, becomes an active surface—a site from which history reorganizes itself as possibility.

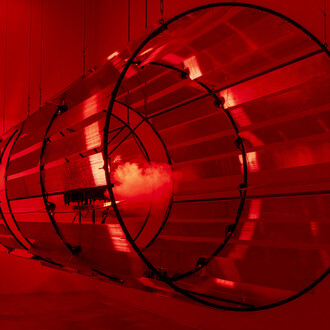

That gesture—of repairing through the fracture, of turning the wound into an active form of thought—structures the very core of Attia’s work. Repair acts as a form of attentive listening, a practice that transforms the wound into a surface for reflection. Each intervention affirms the continuity of what is alive; each assembled fragment contributes to a poetic architecture that expands memory. The image gains value through its ability to gather layers, temporalities, and materials—to hold multiple histories in creative tension. In this practice, form does not reproduce: it creates. It traces scenes where sensitivity becomes presence, and where time condenses into a fertile instant. Beauty emerges in the careful arrangement of what is dispersed, in the sustained attention to what remains.

In that dense and open space, the work configures a visual ethics that shelters, transforms, and projects. From there, poetry reveals its foundational force: a sensitivity that embraces the fracture and gives it form. The poetic dimension of these works configures form and reveals thought. Each image, each composition, generates a space where the word becomes matter, where the visual gesture opens the possibility of another gaze. Poetry, understood as the language of the essential, offers humanity a fertile ground for imagination—a space where hope grows as practice and presence. Within that horizon, committed works activate the political through emotion, through the density of the sensible, and through the shared strength of the common.

Perhaps, then, the lost paradise of which Baudelaire spoke emerges as a possibility in becoming: a hope constructed from the fragments that still resonate through history, a form of future inscribed in the gestures of the present. In the work of Kader Attia, beauty flourishes in the cracks, in unfinished forms that hold memory, in repaired surfaces that sustain meaning. Each wound opens a field of creation; each gesture of repair affirms the power of coexistence between the diverse, the displaced, the recombined. In that landscape of fertile fractures, memory acts as a driving energy, and art as a site of reappearance—a space where absence transforms into active presence. Baudelaire, in his journey toward the unknown, intuited it: “Those who leave just to leave… / Those whose desires have the shape of clouds” (Le voyage, 1857). Paradise does not lie in the origin, but in the movement that reinvents it.

(Text by Jimena Blázquez)