The first article I wrote for this magazine, almost five years ago, was titled ‘Wither the Washington Consensus?’ My answer was ‘no’, because there certainly was a new discourse on poverty and social protection, but the practice of international financial organisations had not changed.

Today, it looks as if the question must be changed: wither the global social agenda?

Social development has always been on the agenda since the beginning of the development cooperation programmes of the 1960s. The General Assembly of the UN adopted some interesting resolutions, such as the one on development and social progress in 1969 and, of course, the 1966 International Covenant on economic, social, and cultural rights, based on the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

The ILO, for its part, adopted several important resolutions such as the1952 treaty on the minimum standards for social security.

However, it was only in 1990, when the World Bank adopted a new slogan, ‘We have a dream. A world free of Poverty’, that the social agenda became concrete. At the same time, UNDP published its first ‘human development’ report and showed how economic growth was never enough to raise the living standard of people. Social policies were necessary.

From that moment onwards, a lot of research started, and social development programmes were put into place. Even if it became clear that the poverty agenda had nothing to do with a change in neoliberal policies, on the contrary, it was only meant to give a human face to it and be used against the development of real welfare states. The austerity philosophy remained in place, without any change.

Countries were asked to draw up poverty reduction strategy papers, a certain flexibility was introduced, allowing for a different hierarchy in the reforms, there was a new discourse on participation, etc. Fundamentally, nothing really changed.

Several UN organisations started to cautiously criticize this approach. The ILO adopted in 2012 its recommendation on social protection floors, a very welcoming proposal, though it did not go as far as the resolution of 1952.

Slowly, slowly, the World Bank also adopted the new vocabulary and started to speak about social protection, though with a very different meaning than what already existed in terms of social and economic rights. For the Bank, it was risk management, and it totally ignored the rights dimension.

The concept of ‘universalism’ also received a new meaning: it did not refer to the whole of the population anymore but, once again, to the poor and ‘those who need it’. It allowed the ILO and the World Bank to sign a Joint Declaration on universal social protection.

The World Bank even published its 2019 World Development Report, pleading for a new social contract, and in 2022, a paper on a social protection compass, aiming at resilience, equity, and opportunity. No mention, however, of human rights.

In the meantime, in 2015, the Millennium Development Goals were met at the global level,and extreme poverty had been halved compared to 1990, but this was largely thanks to poverty reduction in China and India.

As for the Sustainable Development Goals, they most probably will not be met at all by 2030.

For a couple of years, all efforts at the global level seem to have stopped.

Much hope was put in the new UN social summit that was to be organised in November 2025 in Qatar. As the date approached, it became clear there was no real social ambition anymore.

Where the Copenhagen Declaration of the first social summit spoke of ‘commitments’, the new political declaration only talks about vague promises. The three chapters on poverty, employment, and social integration were maintained and completed with some interesting cross-cutting points on food security, access to land, price stability, health care, quality education, and so on. There were a few controversial points simply because of the lack of interest of member states.

At the annual meeting of the World Bank and the IMF in November, there was only talk of ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’, without any reference to poverty, wages, or other social policies.

The World Bank had to admit that poverty is not diminishing anymore. In 2025, it added almost a hundred million extremely poor people to its statistics. There are now as many poor in Africa as there were in 1990. Several African countries still have poverty rates above 70 %.

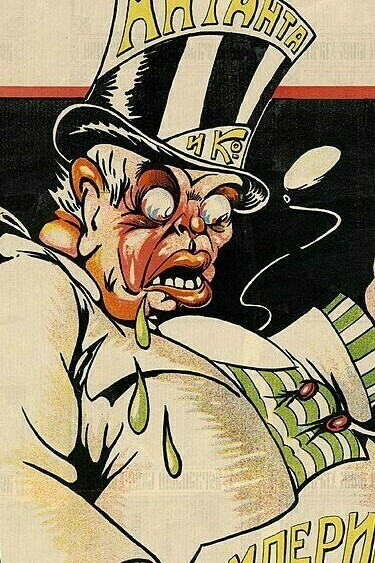

This has nothing to do with a lack of resources. Inequality is growing at rates never seen before. Each year, Forbes’ list of billionaires gets longer.

Moreover, several rich countries with well-developed welfare states are now rapidly dismantling their pension systems, health care, childcare, and unemployment policies, etc. After thirty or forty years of ‘austerity’, now starts the era of ‘real reforms’ which, without any doubt, has to be understood as a total dismantlement of welfare states.

The last Global Rights Index of ITUC in spring 2025 spoke of a serious deterioration of labour rights, not only in the South but also in wealthy countries.

In magazines such as The Economist, there are now once again articles on the damage minimum wages can do or the problems with universal child benefits.

In short, it looks as if the era of social development and social protection is over again.

The ILO courageously goes on defending its core business with an interesting document on the human right of social security, but it is hampered by a lack of resources compared to what organisations such as the World Bank and the IMF can do in countries of the South.

At the G20 meeting in South Africa in November 2025, a social summit was organised, calling for solidarity, equality, and sustainability. It aimed to place social development, equity, and inclusion on par with macroeconomic and financial matters and to foster global solidarity.

The final Declaration of this G20 summit calls for reducing inequality and for working at good quality jobs and decent work. It also calls for ‘universal and adaptive social protection as essential to reducing inequality’.

Also, a new initiative was taken by the UCLG, the United Cities and Local Governments. They state that cooperation is possible and transformative and want to advance a multilateralism that delivers. They adopted a Local Social Covenant in order to connect local action and global ambitions. The Covenant calls for the provision of local public services in housing, food systems, health, and local care systems.

So, not everything is lost. We might be heading for a new vision on social protection. This certainly deserves more attention and will need new research.

Rights and the far right

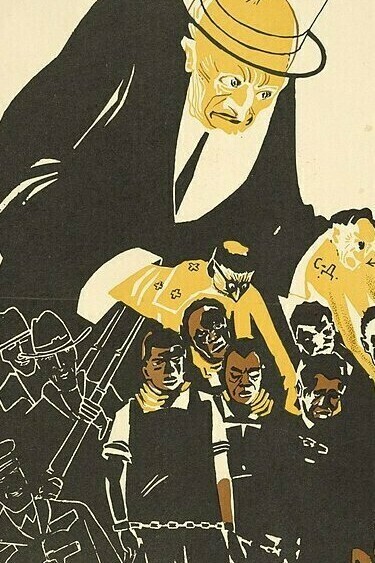

The UN Special Rapporteur for poverty and human rights published a very interesting report some months ago. It speaks about the links between the growth of the far right and the dismantlement of economic and social rights.

The rapporteur, Olivier De Schutter, mentions three problems.

The growth of what he calls ‘far right populism’ is a consequence of the dismantlement of people’s rights. Welfare became workfare, and people are ‘activated’ to enter the labour market. Secondly, digitalisation of many tasks makes life a lot more difficult for many people, and thirdly, all those who, irrespective of the reason, cannot participate in the labour market anymore, are branded as ‘losers’, stigmatised, and often criminalised.

The rapporteur proposes three different strategies to counter this trend.

First, make social protection really universal; secondly, let it work as a bridge between different communities in our diverse societies, and thirdly, create confidence, public authorities need to offer a helping hand instead of multiplying sanctions.

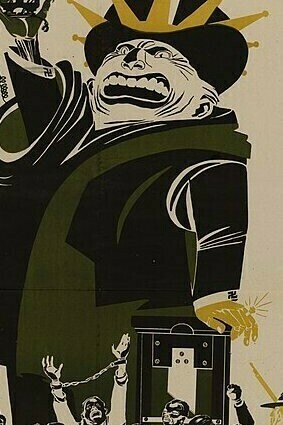

Redistribution, according to De Schutter, is far more than an economic element. In fact, it is highly political and helps to make cohesive societies, a condition for democracy.

It is a fact that in all parts of the world, democracy is threatened. This is why ITUC has made this topic central in its action, and there are very good reasons indeed to do so. A ‘Democracy that delivers’ pleads for institutions that reflect the will and meet the needs of the majority of workers worldwide. This is essential for the cohesive fabric of societies.