There’s a rhythm to every classroom. It’s the subtle buzz of anticipation before the teacher arrives, the hushed alliances forming in group projects, and the invisible calculations happening behind students’ eyes. Who will I sit next to? Who will lead the group? Who knows what they’re doing? But beneath the surface of everyday routines lies something deeper, an undercurrent that shapes interactions, opportunities, and experiences: student bias.

This bias doesn’t often shout. It whispers. It slides into decisions almost unnoticed. It’s there when one student hesitates to partner with another because of their accent. It appears when someone assumes a peer won’t contribute much because they’re quiet or dress differently. It shows up when subjects are labeled—math is for the “smart ones,” arts for the “dreamers,” science for the “boys.” These aren't overt acts of hostility; they're quiet exclusions, formed by assumptions and absorbed through culture, upbringing, and years of subtle messaging.

Student bias is not merely about how learners see others; it is also about how they see themselves. Many students walk into classrooms already believing there are certain things they’re not good at. These beliefs often have nothing to do with their actual abilities and everything to do with the silent messages they’ve received over time. Maybe no one in their family went to college. Maybe they’ve never seen someone from their background celebrated in a math competition or quoted in an English textbook. Over time, these messages crystallize into convictions. “I’m just not good at science.” “People like me don’t become leaders.” These aren’t reflections of reality. They are reflections of bias often internalized before students even realize it.

Bias doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It’s learned, often quietly, through early childhood experiences, media portrayals, and the stories children hear and see. Children absorb what they witness. If they constantly see leaders who look a certain way or successful students portrayed with a particular demeanor, they begin to believe that success has a type. If adults around them casually dismiss certain groups, those dismissals linger, taking root in impressionable minds. Eventually, these perceptions carry into classrooms, shaping how students form groups, whom they listen to, whom they ignore, and how they rank themselves.

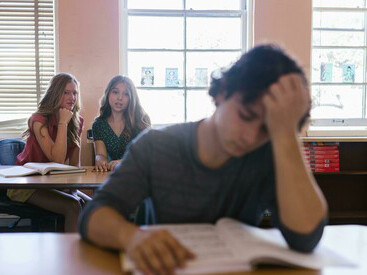

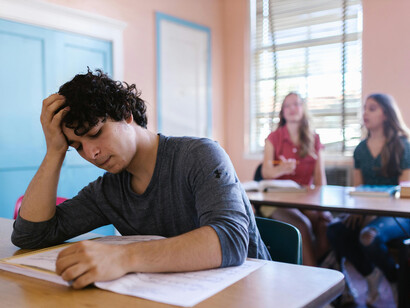

The consequences are not always immediate, but they are deeply impactful. Students who are consistently overlooked or underestimated may begin to retreat. Over time, they may stop volunteering, stop challenging themselves, or disengage altogether. On the flip side, students who are consistently chosen, praised, or followed, sometimes because of bias rather than merit, may never recognize the limitations of their own understanding. Relationships are affected too. Bias can prevent real friendships from forming, divide classrooms into invisible factions, and leave some students feeling perpetually on the margins.

And yet, even within these heavy realities, change is possible, often beginning with the smallest of moments. A student who assumed another wasn’t capable might witness an insightful presentation and feel a shift. Another who’s always been seen as “average” might receive praise for a surprising talent and discover a sense of self-worth they hadn’t known before. These realizations don’t happen through force. They happen through awareness and exposure. And once they do, they can alter the entire landscape of a student’s experience.

So, what can be done? How do we break down the quiet walls that student bias builds?

It begins with creating reflective classrooms—spaces where students are not only taught content but are also encouraged to think critically about how they engage with one another. When learners are asked to examine why they might have chosen certain partners or formed particular judgments, they start to see the patterns of exclusion they may have unconsciously participated in. These reflections aren’t about blame—they’re about growth. About seeing clearly.

Another vital approach lies in group dynamics. Instead of allowing students to always self-select, teachers can facilitate diverse groupings, rotating roles and responsibilities so that every student engages with every other, eventually. This pushes students beyond comfort zones and dismantles assumptions. Collaboration with unfamiliar peers often leads to unexpected respect, deeper understanding, and the slow erosion of stereotypes.

Equally important is how we define and celebrate strengths. When classrooms value only one type of intelligence, typically verbal or mathematical, students who excel in creativity, empathy, or hands-on problem-solving are left feeling “less than.” By widening the lens and honoring multiple forms of excellence, students begin to see both themselves and others in fuller, more generous ways.

Representation matters deeply in this equation. If students constantly see success portrayed through a single demographic or personality type, they begin to associate achievement with identity rather than effort. Bringing in stories, examples, and guest speakers from a wide range of backgrounds, life paths, and learning styles helps reshape these narratives. It tells students, You belong here. Your voice matters.

Above all, combating bias means nurturing curiosity. At the heart of every assumption is a failure to ask deeper questions. When students are encouraged to wonder: Who is this person? What might I not know about them? They shift from judgment to connection. Curiosity opens doors. Bias closes them. Teaching students to be curious not just about content but about people may be one of the most powerful lessons an educator can impart.

Of course, change is slow. Biases, especially the quiet, polite ones, don’t vanish overnight. But they begin to weaken the moment they are named, challenged, and replaced with understanding. Every time a student discovers a classmate’s hidden talent, every time they confront a false assumption about themselves, and every time they make room at the table for someone new, they are participating in this change.

In the end, the goal isn’t to raise perfect students who never misjudge anyone. It’s to raise thoughtful students who are willing to notice when they do, who choose kindness over convenience, and who recognize that learning is not just about facts and figures but about becoming better people.

Bias thrives in silence, in habit, and in the comfort of sameness. But awareness, reflection, and human connection—these are its antidotes. And the classroom, perhaps more than any other place, is where this quiet revolution can begin.