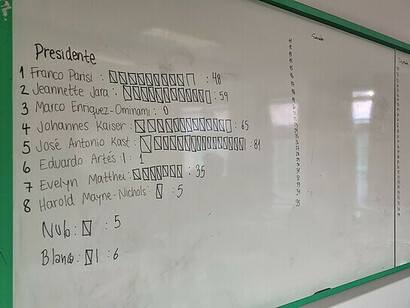

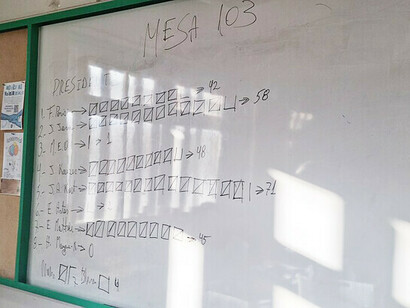

In the recent Chilean elections, the right-wing candidate José Antonio Kast (59) won a resounding victory with 58.16% of the votes, against Jeanette Jara (51), who represented a broad coalition of center-left parties, including the weakened Christian Democracy (DC), and obtained 41.84%. Approximately 7% of votes were invalid or blank, while voter turnout reached 85.06%, with a total of 13,421,650 people voting.

Compulsory voting was reinstated in Chile in 2023, adding nearly five million people who did not participate in previous elections. Kast's lead of 16.3 points is the biggest defeat for the left since the return to democracy in 1990. He won in all 16 regions of Chile and 310 of the country's 346 municipalities or city councils.

Jara left her position as Minister of Labor to run for office and has been a member of the Communist Party (PC) since the age of 14. She represented continuity with President Gabriel Boric's government, which is ending its term with public approval ratings of less than 30%. Of Jara's 41.84% of the vote, a sizable proportion came from individuals who, when faced with choosing between the far-right candidate and one representing a broad coalition of left- and center-left parties, opted for the latter. The PC's average vote in parliamentary elections since 1990 has been 4.4%, reaching only 4.9% in the last three elections between 2017 and 2025.

In fact, the right held its own primary in the first round of the presidential election, fielding three candidates. It won a total of 50.3% of the vote — the highest result since 1990. The remaining four candidates won 22.82% of the vote, which subsequently mainly went to the winning candidate, Kast, in the second round. As all the polls had predicted, the scenario was very difficult for candidate Jeanette Jara. This defeat is a major setback for President Boric's government and the broad alliance that has supported him, and recriminations between parties and accusations against the government have already begun.

It is too early for an in-depth analysis, but the parties must engage in profound self-criticism, particularly regarding their future role as the opposition to President Kast's government, which begins on 11 March 2026. The central question is whether it will be possible to maintain a broad alliance between liberal, regionalist, green, humanist, DC, Frente Amplio (FA), Socialist Party (PS), Party for Democracy (PPD), Radical Party (PR), and PC sectors. To answer this question, some historical context is required.

The return to democracy in the 1980s was laboriously promoted by 17 parties that formed the Concertación por la Democracia (Coalition for Democracy), to which the Communist Party did not belong. From 1990 onwards, Chile experienced its best years in terms of economic growth, significant poverty reduction, and expansion of education and consumption. This period has been characterized as a process of accelerated capitalist development, to which the first center-right government of former President Sebastián Piñera (2010–2014) also contributed. However, things began to change in 2014 when President Michelle Bachelet, in her second term, incorporated the PC into her administration, effectively bringing an end to the Concertación. This enabled the communists to join the government, gain legitimacy from the center-left, and increase public exposure. Under the Boric administration, they gained a significant presence in the cabinet, occupying key ministries and becoming part of the political committee.

The PC is a party with over 100 years of history in Chilean politics and has always operated within the confines of the law in a democratic framework. However, it is an orthodox party that has never engaged in self-criticism regarding what Soviet communism represented in the USSR and other countries. It has never condemned the lack of freedoms in Eastern Europe or Cuba, the construction of the Berlin Wall, or the invasions of Hungary, the Czech Republic and Afghanistan” At its 17th congress in January 2025, held in Santiago, it was agreed to: “strengthen the Party on the basis of our principles, such as democratic centralism, unity in action, revolutionary vigilance, conscious discipline… Marxism, Leninism and feminism reaffirm the Leninist principles of organization with a focus on revolutionary vigilance. The proposal was made to set up cadre schools with regular monitoring, including contributions from communist parties in other countries1”.

In other words, it is a party that continues to view reality through the lens of the 20th century in a world that has changed. Western communist parties no longer exist, or they are electoral minorities. The PC continues to support Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua in Latin America. The PC will undoubtedly call for the mobilization of the hard left and the formation of a broad front or alliance to oppose the Kast government. This would help to maintain its legitimacy alongside social democratic and other forces. However, this is the same approach that it took in the presidential election, with the results that we already know.

Conversely, President Boric's party, the FA, which aspires to set the standard for the new Chilean left, has credibility issues following its time in government. Although Boric has demonstrated maturity and a shift towards social democratic positions — which he previously denounced — he must consolidate his leadership. He will be confronted with his government's unfulfilled promises, such as ending neoliberalism and the "moral superiority" touted by his closest collaborators.

Leading figures in the FA considered themselves to be a vanguard party with dreams of revolutionary change that would put an end to neoliberalism. They have never abandoned this belief, maintaining it with arrogance and in opposition to reality. Their strength lies in their ability to mobilize a considerable proportion of young people. The FA and the PC bear much of the blame for proposing a new constitution that was rejected by 61.89% of Chileans in 2022. One of the PC's leaders, Daniel Jadue, blamed President Boric directly for the electoral defeat, while socialist senator Fidel Espinoza blamed the FA and the government.

The social democratic group formed by the PS, PPD, and PR is known as 'democratic socialism' and is supported by liberals, environmentalists, humanists, and Christian democrats. This group is known as 'progressivism' and strongly defends the years of economic growth and improvement in living conditions for most of the population generated by the Concertación. However, they performed poorly in the parliamentary elections held alongside the presidential elections, with the PS obtaining 5.4% of the vote, the DC 4.2%, and the PPD 4.0%. The FA obtained 7.5% and the PC obtained 5.0%.

Additionally, the other members of the alliance — radicals, humanists, and environmentalists — did not reach 5% of the vote in any region, nor did they manage to elect at least four parliamentarians, as required by law, so they are in the process of dissolution. The majority obtained by right-wing forces in both chambers of Parliament will not be sufficient to make constitutional changes.

Despite having very different political views, these three ideological sectors were able to present a united front in the election, with Jeanette Jara as their candidate. Today, they must define their destiny and find common ground if they are to win back part of the electorate. The PS and the FA are competing for hegemony within this group. This has led the president of the PS, Senator Paulina Vodanovic, to declare that her party is left-wing rather than center-left, though she has not clarified what this means. Some are suggesting the possibility of rebuilding the socialist-communist alliance of the 1970s that led to the election of former President Salvador Allende.

One of the momentous decisions to be made is whether to continue as allies in a political project with the PC, whose views on society, the state, and international politics differ greatly. The PC has repeatedly called for 'taking to the streets' or 'having one foot in the government and the other in the streets', which has often led to scenes of violence and destruction by small radical groups. Those on the social democratic and progressive side argue that it will take time to regain public confidence and that they must clearly differentiate themselves from the PC's ideological vision by reaffirming the reformist path of social democracy.

The emergence of new leaders and the role of Gabriel Boric from next March will be key, as he will have to keep his party united while new leaders emerge. There is also a very small possibility of a 'perestroika' within the PC, and Jeanette Jara's role in remaining relevant will be defined. The PS will have to choose a policy of alliance: with the FA and/or the PC, or with the progressive and social democratic sectors to which it and the DC belong. Together, they formed the central axis of the successful years of the Concertación. The PPD has taken the initiative by setting out a proposal in a document that calls for the formation of a new force that unites the various progressive groups while excluding the communists. Parliament will be where the left and center-left forces confront the government and the most hardline right-wing sectors, and where various alliances are forged.

Chilean society has undergone profound transformations characterized by a preference for the private over the public. This is particularly noticeable in education, health, and pensions, where access is determined by income level. Likewise, mass immigration has brought changes and has been associated with an increase in crime. Fear of crime cuts across all social sectors, a fact that neither the government nor the left-wing parties properly understood. Notably, all three right-wing candidates supported Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship.

Even more notably, Kast will be the first elected president to openly admit this and receive significant public support. According to academic David Altman, this confirms that the cleavage that marked Chilean politics for 32 years, based on whether people voted for or against Pinochet in the 1988 plebiscite, has ended. The new cleavage will be the 2022 constitutional referendum, in which the maximalist proposal for a new constitution presented by the hard left was rejected by a majority just six months into Boric's administration. In other words, the military dictatorship would be consigned to history, and it remains to be seen whether this new divide will endure over time.

However, this thesis has been quickly refuted by another academic, Andrés Dockendorff, who points out that it is not sustainable. Although there appears to be a correlation between Kast's vote and the rejection of the 2022 constitutional proposal, no dividing line of this kind has been established, nor have the proposals been adopted by the parties as an ideological element. It should be noted that some on the left also disapproved of the proposal. Other preliminary studies suggest that compulsory voting, with fines for non-compliance, played a role, as five million people who were previously not voting, mainly from vulnerable sectors, did so, mostly for Kast.

In other words, a silent, conservative vote emerged. Specialists must answer the question of whether it was an ideological vote or one driven by the fears that haunt Chileans. Another factor to consider may be social fatigue with the "woke" agenda that some sectors of the Boric government pushed to the extreme, replacing traditional functions, such as that of the first lady who covered social aspects; animal rights, feminism, environmentalism that has slowed many investment projects, indigenism in a country where only 10% of the population declares itself to belong to an ethnic group, issues of gender identity, languages and others. It also covered gender identity issues and language. In some cases, this agenda has been taken to extremes, causing rejection and fatigue. These issues were not absent in the previous government, but they were catapulted beyond what is reasonable for a conservative society.

In short, the left still has a long way to go to regain the people's trust. The four-year electoral cycle without immediate re-election is very short. On 11 March, those who feel called to be the next president will be eager to begin their campaign. The right and its parties will also face rivalries, competition, and disloyalty, and will likewise be looking ahead to the next election.

Kast will have to manage a group of parties supporting him, ranging from the far right and conservative religious groups to the center-right and moderates, as well as small groups of opportunists. If Kast's government prioritizes prudence and authority, fulfills its basic promises of security and curbing irregular immigration, implements austerity measures, and grows the economy by expanding investment and employment, while not altering the already won rights in terms of values, Chile could enter a cycle of right-wing governments somewhat like the Concertación between 1990 and 2004.

Notes

1 Link to the document Resolutions of the XXVII National Congress of the Communist Party of Chile.