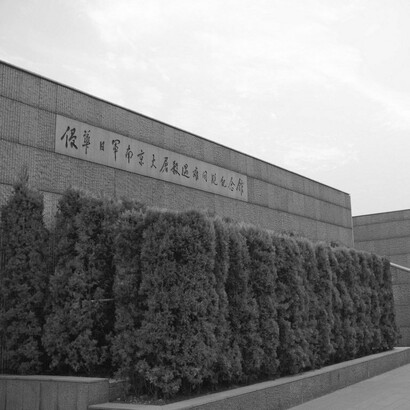

China’s most successful movie in years swept the box office this summer. Dead to Rights is still showing, pulling audiences into an emotional roller coaster as they witness truly horrific and gruesome scenes of the massacre the Japanese carried out when they occupied Nanjing in 1937 and identify with a group of survivors trying to escape, carrying the photographs that would eventually expose the mass atrocities to the world.

It was this emotional tinderbox that Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi ignited when she said a military threat to Taiwan would spur military intervention by the country’s Self-Defense Forces. Nearly a month later, commentators continue to ask themselves what on earth Takaichi, the country’s new leader, had in mind in blurting out such a provocative statement on such a sensitive issue at the climax of Beijing’s year-long campaign marking the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, which focused on memorializing the 15-20 million Chinese who perished at the hands of the Japanese Troops.

China’s response was immediate and angry. Aside from taking Takaichi to task for intervening in a domestic concern, Beijing discouraged its citizens from traveling to Japan, and its consul general in Osaka posted on X that “the dirty neck that sticks its neck in must be cut off.” A ban on Japanese seafood exports to China was announced, and a large number of planned concerts by Japanese entertainers were cancelled, with Japanese singer Maki Otsuki stopped in the middle of a song during a concert in Shanghai. The latest casualties are youth exchange programs between the two countries, with Beijing apparently adamant that things will not return to normal until Takaichi retracts her statement.

Firestorm on the net

Not surprisingly, Takaichi’s comments triggered an internet firestorm in China, where the Prime Minister has the image of being a hawkish protégé of the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who represented for many Chinese the unreconstructed, unrepentant attitude of many Japanese towards their country’s World War II era war crimes. While not exactly a “denialist” as many other Japanese right-wingers are on the issue of war crimes, she has questioned the accuracy of the accepted narrative regarding the Nanjing Massacre and other atrocities committed by Japan in its 14-year attempt to conquer China.

What exactly did Takaichi say? At a parliamentary budget hearing, she asserted, in response to a question, that an attack on Taiwan involving warships would represent a “survival-threatening” situation that would require Japanese military intervention. Taiwan belongs to China, but functions as a de facto sovereign state under the informal protection of Washington. Previous Japanese prime ministers had never specified how Japan would respond to a Chinese military move against Taiwan. As one observer put it, “The difference in Takaichi’s remarks was less the content of what she said, and more the directness1 with which she said it. Her comments could perhaps be interpreted as moving further away from Japan’s version of a ‘strategic ambiguity’ policy, by directly linking Japan’s own security with the security of Taiwan.”

A mistake?

The most benign interpretation of Takaichi’s words was that they were uttered in the context of a parliamentary debate by a prime minister who was still learning the ropes and made an error of making explicit a course of action best left vague. Those taking this view say it could not be reconciled with the tenor of a meeting between Takaichi and Chinese President Xi Jinping just over a week earlier on the sidelines of a regional meeting in Seoul, where both pledged to work towards “stable and constructive relations.” In this view, it was Beijing that was at fault for “overreacting.” Moreover, although Takaichi refused to retract her words, as demanded by Beijing, she did say that she would refrain from making such statements again.

There are those who discount the “clumsy politician” argument and say it was deliberate, a ploy to strengthen her shaky domestic standing by adopting a strong image in foreign policy. They point out that, aside from being a disciple of Abe, she sees the late Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady,” as a role model. But to disrupt relations with China, Japan’s second most important, if not most important, foreign policy relationship, for the sake of a small and fleeting domestic political dividend, does not seem credible to many.

Continentalists ascendant?

The most likely explanation, in my view, has to do with Donald Trump, whose visit to Japan in late October was one of the highlights of a week-long swing through the Asia Pacific region. Prior to Trump’s visit, the whole region was apprehensive about Trump’s second presidency. Though Trump had declared a trade war on practically all countries, the East Asian countries, the so-called Asian Tigers that had built export-powered economies, were his special targets. Nearly all the Southeast Asian countries were penalized with a 19 per cent tariff increase, while Japan and Korea were each punished with a 15 per cent rise under Trump’s blanket justification that both enemies of the US, like China and its allies, had taken advantage of its American “generosity.”

Washington’s Northeast Asian allies, Japan and Korea, however, were concerned with more than trade. Over the last 80 years, they have served as protectorates on the frontlines of the American Empire in Asia. At the end of the Cold War, they hosted hundreds of bases and facilities from which the US Pacific Command could project power towards the Asian mainland. When Trump brusquely told them to shoulder more of the costs for their defense during his first term, they began to worry about their security umbrella, and they were not unrattled in 2019, when he crossed the Demilitarized Zone to shake North Korea’s Kim Jong Un's hand and pat him on the back. When Trump came back to power earlier this year, the conservative elites in Seoul and Tokyo became alarmed that the old containment policy of the last 80 years had become a bone of contention within the new foreign policy team.

They were disconcerted by reports coming out of Washington that, as one analyst summed it up, three factions2 were struggling for influence in Trump’s inner circle: First, the “maximalists”—a dwindling group that still clings to the dream of global American dominance. Then come the “specificists”, led by Elbridge Colby and his allies, who believe America must retreat from Europe and the Middle East to focus single-mindedly on China. Finally, the “continentalists”, or “neo-Monroeists”—Stephen Miller and Vice President J.D. Vance, chief among them, who advocate an almost hermit-like retrenchment, turning the U.S. into a fortress continent.

By mid-year, the Koreans and Japanese were getting really alarmed. Trump seemed to be recognizing Russia’s suzerainty in Eastern Europe, the NATO allies were left to fend for themselves in Ukraine, and the US was attacking Venezuelan boats on the pretext that they were drug dealers while positioning more and more ships, including an aircraft carrier, close to Venezuela. It seemed that the US was putting its military focus on the Western hemisphere, meaning the isolationists or continentalists were gaining the upper hand.

What was especially disconcerting was that no clear policy posture was coming out on the Asia-Pacific from the White House, and while Peter Hegseth, the Secretary of War, visited the region earlier in the year and muttered the old Cold War shibboleths, the fears of Seoul and Tokyo were not assuaged. It seems like Washington was informally adopting a spheres of influence strategy.

The visit of Trump in late October on the way to attend the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Seoul provided an opportunity for the Japanese to get more definitive statements from Trump on the future of the US security shield. Takaichi played up to his vanity, promising to nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize. But all Trump was interested in talking about was more investment by Japanese corporations in the US, even when she promised “to take the Japan-US alliance to a higher level with President Trump”.

Thrown under the bus?

Was Takaichi’s throwing off strategic ambiguity on the Taiwan question a move to get Trump to make a more definitive commitment to maintaining or upgrading the military alliance with Tokyo? If the intent of Takaichi’s remarks on Taiwan was to elicit a strong affirmation from Trump of the US-Japan security relationship and that the “collective security” principle would entail coordination in the event of a Taiwan contingency, she was most likely disappointed. In his account of a telephone conversation between him and Chinese President Xi Jinping a few days after Takaichi’s remarks, Trump said he had “a very good telephone call with President Xi, of China. We discussed many topics, including Ukraine/Russia, Fentanyl, soybeans, other farm products, etc. Our relationship with China is extremely strong!” There was no mention of support for Takaichi’s position, nor even some acknowledgement that the Japan-Taiwan issue was discussed. Equally suggestive was the tone of his post, which was respect for Xi, if not enthusiasm.

In a telephone call with Takaichi the next day, instead of giving her the backing she wanted, Trump apparently told her to avoid further actions that might inflame the dispute with Beijing. This was practically an acknowledgment that she was to blame for the row. Reflecting on Trump’s comments, a respected analyst, Zhu Feng3, Dean of the School of International Studies at Nanjing University, suggested that Washington was “unwilling to let the Taiwan issue be used to hijack China-US relations” and that “Trump’s domestic and foreign policy priorities have not focused on Taiwan or the Asia-Pacific.”

To many in Japan and the Asia Pacific, Trump’s fawning account of his conversation with Xi and his telling Takaichi to dial down the rhetoric are one more indication that the isolationists or continentalists are ascendant and that Trump is in the process of informally ceding the Asia Pacific as China’s sphere of influence. Indeed, many analysts claim that Trump’s non-declaration of support was really an act of throwing Takaichi under the bus.

A long winter ahead?

Many observers talk about the onset of a “long winter” in China-Japan relations, and that Tokyo is on the losing end of this protracted conflict. What many Japanese, foremost of which is Takaichi, an unreconstructed hawk, do not seem to understand is that for China, the Second World War is not over and that Beijing will not ease the pressure until Tokyo cries uncle. For a rapidly aging society that is, in economic terms, being left far behind by its rival (China’s GDP is over four times that of Japan), that is suffering from technological stagnation, whose military is having a tough time filling its recruitment quotas, and whose protector no longer considers the alliance a priority, that is a very daunting future. Takaichi’s poll numbers are said to have gone up, but they’re likely to plunge once the pain of having recklessly offended an ascendant nation to whom the country owes a blood debt is felt.

Will Takaichi repent and retract her statement? Perhaps before she decides on a definitive course of action, it might be a good idea for her to arrange a special screening of “Dead to Rights” for herself and her fellow hardline rightists. Better yet, she could arrange for the screening on TV and in movie theaters of “Dead to Rights” to push the Japanese to finally come to terms with a dark episode in their past that many prefer to erase from the collective memory.

Notes

1 The PRC’s Diplomatic Offensive Against Japan Over Taiwan on Global Taiwan Institute.

2 Southeast Asia at a loss at the end of the American Empire on Nikkei Asia.

3 Trump’s calls with Xi and Takaichi hint he won’t let Taiwan derail Beijing ties on SCMP.