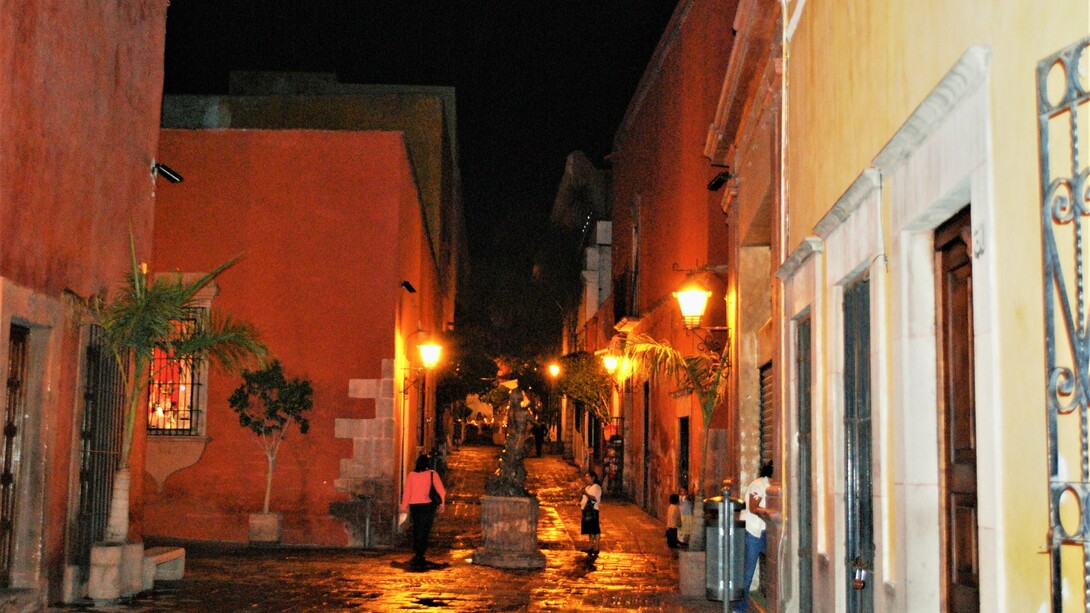

My flight is late, and by the time I arrive in the city, my cab is traveling along winding cobblestone streets heading to my hotel. Night has set, and the streets of Santiago de Querétaro are lit by the silvery rays of the moon, creating scenes of this 16th-century Mexican city that are picture-postcard perfect. An elderly couple, he with a hat jauntily perched on his head, she with a white lace shawl draped on her shoulders, walking, their arms entwined, along the narrow sidewalks. A glimpse into a courtyard overflowing with flowers beyond an iron gate. Old-fashioned streetlights illuminate sunset-colored buildings. Light spilling from open doors shows the interior of busy restaurants. All accompanied by the soft calls of song birds and the scent of jasmine floating through the soft night air.

There’s a flow between the past and the present in Querétaro, one of the wealthiest cities in Mexico, as well as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A center for commerce and tourism, Querétaro is found in an area of mountains and lush growing fields north of Mexico City in what is known as the Colonial Highlands. The next morning, I walk the few blocks from where I’m staying at the Doña Urraca Hotel & Spa, known as a prime example of colonial architecture, to the fairy castle-like La Casa de la Marquesa, once a private home built in 1756, now a restaurant and hotel. The menu reflects the region’s vast citrus groves, ranches, cactus, and cornfields.

Plump figs, recently picked, sit on platters in the ornate dining room near pitchers filled with fresh oranges squeezed with cactus or beet juice. The meat comes from nearby cattle ranches; the cheeses and wine are local as well. All are brought to the table by female servers dressed in garb that I first thought was from another era of Mexican history, but which I am told was designed to look like what Mary Poppins might have worn if there had been a Mary Poppins. I don’t point out that Julie Andrews was wearing nothing like these frilly dresses in the movie.

My host recommends Encarcelados – layers of fried eggs, beans, and ham topped with green sauce and crispy pork skins (a very popular food here and though not at all healthy, much tastier than the pork rinds sold in the U.S.). All is accompanied by seemingly non-ending streams of hot coffee and crema caliente or hot cream served in delicate porcelain cups. Instead of saying no more, I make the decision not to worry about calories. After all, I will be walking extensively in my exploration of the historic district, known for its fountains, city gardens and brightly painted buildings with wrought iron balconies, oversized carved wooden doors and, of course, this being Mexico, the most wonderfully ornate churches, many in a Spanish baroque-architectural style characterized by elaborate exteriors of decorations and engravings and known as Churrigueresque.

At one time, this part of Mexico was ruled by the Spanish, who plundered the great wealth of silver and gold from the nearby mines and created magnificent mansions and cathedrals with 24-karat gilt and beautiful frescos, altars, and art. Besides Churrigueresque, they left another architectural style—that of Mudéjar, a fusion of Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Islamic art created between the 12th and 16th centuries by the Muslims who remained in Spain and Portugal after the Spaniards wrested the land back from their Moorish conquerors.

In Querétaro, a prime example of Mudéjar is La Casa de la Marquesa, with its elaborately intricate, astonishingly elaborate mosaic walls and floors, intricately arched doorways, and second-floor colonnades accented by silver overlays on the many stairs and crystal chandeliers.

Mudéjar is also represented in the architecture of Santa Rosa de Viterbo, just one of over 40 elaborate and ornate churches in the city. Its most unique feature is two curling and immense buttresses that jut from either side of the entranceway, which are painted to look like snail shells.

The ornate and opulent interior of the church, not unusual in colonial cities, is a gilded mirage with marvelous arches, choral lofts, lush oil paintings set in medallions of elaborately carved plaster, and a Baroque altar that dates back to when the church was built in the mid-1700s.

There’s over-the-top creativity in this ultra clean city (there always seem to be uniformed groups hosing down the streets), and I peek into a restaurant and bar that was once an old apothecary shop whose interior shelves hold painted ceramic jars once filled with healing herbs, and small drawers that once held pills are tucked into the length of a back wall. The city is made of public squares, each with a fountain and often a statue or two as well. Food vendors sell candies, cook tacos on hot griddles, and slice fruit that is then rolled in spices. A gaggle of schoolgirls in uniforms asks if they can take my photo and wants to pose with me. Most restaurants, if there is space, have outside seating since the weather is almost always fair.

Queretaro, though it has sophisticated cuisine, is also famed for its enchiladas, which are stuffed with beans, Oaxaca cheese, potatoes, and topped with a red chili sauce or a cream sauce and often served with horchata, a sweet rice water drink common in Mexico. Guacamole with pork rinds for scooping is served with almost every meal, including the oyster and octopus tacos (much better than they sound) we taste later that night at Harry’s Bar, which features a blend of New Orleans and central Mexican cookery. And then there are the foods cooked and served in molcajetes—bowls made of thick stone.

Evenings, after exploring the cathedrals with their 24-carat gold interiors, following the street musicians as they play traditional Mexican folk songs, and foraying into shops to hunt for trinkets to take home, I end with a stop at one of the many hot chocolate and churros (fried pastries) shops that dot the walkways. And each night, I promise myself that I will walk an extra mile or so tomorrow, not only to see more sights but to hopefully leave a few calories behind before I go home.