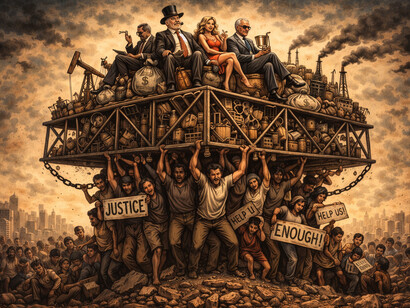

I am convinced the left/right, capitalist/socialist ideological divide is alive and well and kicking as the world’s political pendulum is desperately trying to regain its center after the free market ideology has been reigning supreme (and maybe go beyond… to the right?).

As under colonialism, under globalization, we live under the rule of ‘Might is Right,’ and, under the rule of that might, human rights just fall between the cracks…

Globalization does not have a human face; it leads to the recolonization of the whole planet. The term "globalization" is a euphemism for a process of domination. Power differentials are at its crux. We cannot wish it away.

But, as opposed to people only having their basic needs taken care of, people having rights makes it possible for claim holders to legitimately claim the same. Additionally, the human rights framework imposes clear obligations on duty bearers (i.e., officers of signatory governments) that must be met. (By definition, rights always carry concomitant correlative duties!). Such obligations include respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights provisions that governments agreed to by becoming signatories to the different UN human rights covenants. And that is the breaking point of the new paradigm: it strengthens our hand to act politically.

What this means in the development context is that states have the duty to improve the fair distribution of and access to the benefits of development. And we have to hold them accountable for it.

Not all forms of growth and development are human rights-friendly. Development has to demonstrably give protection to the most vulnerable and impoverished in society to be fully human rights-friendly.

The values we must advocate for from now on under the new human rights paradigm are thus underpinned by international human rights law that, in the future, needs to be incorporated into national laws—in part through our future political struggle for this and through our action as watchdogs of their enforcement. Our human rights work should, therefore, begin at home.

In the human rights framework, the duty to fulfill the rights of children and women, for example, does not depend on economic justifications or excuses.

Pleading guilty

Democracy and human rights are interlinked and mutually supportive.

As development workers acting as political activists, we have to be willing to come into conflict with the ideology of the ruling minority any time it disregards human rights. For that to happen, we need to demystify the ideology of power taken as being neutral in the ruling development paradigm.

But this concept clashes with our prestige as intellectuals, having so far depended on laying claim to being ‘rational and apolitical,’ in short, espousing the ‘ideology of the extreme center.’

Moreover, objectively, there is not yet among development workers a felt responsibility for the creation of national and international conditions favorable to the realization of human rights.

Because of that, I think most of us stand accused of our complacency towards the status quo and violations of human rights, for our lack of criticism of the overall lack of progress in development, for our political naiveté (or our choice not to get involved in the politics of it all), for our uncritical pushing forward to do ‘something’ and get things done and over with, and for our paternalistic and ethnocentric approach. In short, we cannot escape taking part of the blame.

What we have not yet done

The implementation of the human rights framework requires, first and foremost, its translation to the domestic level. Snail-pace progress in development cannot be invoked by governments to justify the abridgment or postponement of internationally recognized human rights. Human rights work will thus require committed leadership and an expanding popular commitment focused primarily on ensuring democracy, improvements in the incomes of the poorest, universal access to and affordability of quality health, education, and other social services, and improvements in the overall living conditions of people (especially women).

As a start, at the country level, we need to check on the follow-up each country has made on major recommendations from international conferences that their governments endorsed when they attended.

The above begs the question: How can the UN agencies and international NGOs be associated with such a hard approach without being accused of political interference? It is hoped they will evolve to higher levels of accountability on human rights issues, carefully treading water in the political arena of each country they are active.

Steps also have to be taken, then, to clarify the universal minimum core content of human rights to be applied in each country to avoid a lenient application of the principles of the Universal Declaration and other human rights covenants. Furthermore, existing standards and policies that are not in conformity with the current human rights regime have to be openly opposed and contested.

Where to start?

In development work, dreaming is OK, but being naïve is not.

On most of the issues depicted in this posting, we do not yet exert effective political leadership. But we cannot run away from, at least, showing intellectual leadership. All of us are called upon to help legitimize and enforce all UN-sanctioned people’s rights, and that requires a crucial change in our conceptual thinking, a change in our mindset.

More than before, defining human rights-congruent, -complying, and -respecting objectives and establishing explicit human rights goals and benchmarks is thus a political task we cannot escape. We urgently need to contribute to the setting up of the legal entities that will define people’s rights more bindingly (e.g., setting up National Human Rights Commissions).

To this, we will have to add all the preliminary work needed at the grassroots and mass organization levels to determine the contents of what these rights are and mean in practice. This will then have to be followed by the launching of the social mobilization and empowerment processes needed to pursue the hard path alluded to earlier.

Additionally, among many others, what we need to do is to:

Strengthen the capacity of development workers wherever they work to apply the human rights principles and to more effectively analyze and act upon the core economic, political, and social determinants of maldevelopment with its preventable ill-health, malnutrition, and preventable deaths.

Overcome the culture of silence and apathy of this staff around human rights issues; this means they will have to work more directly with communities on their violated rights.

Challenge and build consensus on political issues related to the human rights of this same staff, perhaps starting with eliminating in their minds the division they see between politics and their professional endeavors.

Move from the politics of the status quo to a politics of global responsibility for the enforcement of human rights (you, reading this, need to become a scholar-practitioner-activist).

Work towards the more liberatory view of social movements (a la Paulo Freire), and do not wait for opportunities, but create them. [Rights have to be taken; they are not given!]

Move from Declaration to Implementation (Gramsci); we need to ‘walk the talk and not talk the talk.’

Link the normative standards of human rights with other developmental processes to proactively change our roles in our professional work.

Monitor the intentions and deeds of governments and donors to implement economic, social, and cultural rights.

The overall call is for us to move from a basic needs to a rights-based approach. In it, beneficiaries are active subjects and bona fide claim holders. In the rights-based approach, duties and obligations are set for those duty bearers against whom a claim can be brought, both nationally and internationally, thus ensuring that the claim holder's needs are met. The added value of the rights-based approach really lies in creating and enforcing the legal accountability needed and in legitimizing the use of political means in the process of enforcing it.

The establishment of national and international complaints procedures is, therefore, also needed. Short of civil society taking up this function on its own shoulders, national and international monitoring bodies will be needed. One can start, perhaps, with eliciting contributions to the formulation and adherence to guidelines that pursue the application of human rights principles. More binding covenants would then have to follow.

Epilogue

What has been said here is not pure rhetoric. There are some important normative messages here. I see the endeavor we are asking our peers to embark on as the opening of the nth chapter of a long-term, painful struggle on these issues that desperately attempts to horizontalize the previous, more vertical dialogue on the topic. We need you to react. Here and elsewhere.

We are in for an exciting new era. We need all the courage we can muster. Wouldn’t you rather become a protagonist than a bystander?

There is a big catch-up task to be undertaken to remedy past wrongs and make the next decade a winning decade for human rights. Never be sorry to be too late.

It is fitting to close with a quote from the Latin American writer Eduardo Galeano, who asked, "What if we started exercising the never-proclaimed right to dream to lead us to another, possible world?"