Weathering is New York-based artist Wang Xu’s third solo exhibition at 47 Canal. In his new sculptures, Wang generates forms that recall the ancient and the modern, bringing together a variety of materials such as translucent alabaster, striated marble, and lustrous gold leaf. Meditating on the conditions of care in the face of looming global tensions, the artist hones in on intimate, local encounters that widen the scope of his community and return him to the essential practice of making art.

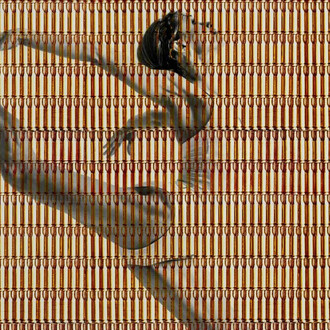

In his work, Wang has examined the winding circuits of globalization and consumerism as they manifest in our daily lives, while engaging in research that foregrounds materiality and the history of sculpture—especially as it exists in public and communal spaces. The artist continues to consider the geopolitical shifts that informed his 2022 solo presentation “a garden has feelings,” reflecting upon changing social patterns and behaviors in the wake of pandemic as well as notions of symbiosis. In Weathering, Wang’s concerns regarding the transnational have converged with those more local. Taking stock of the sites he frequents near his studio in Maspeth or the classes he teaches in Flushing, or those he passes on his usual subway commuter routes, the artist observes our parochial tendencies and the transactional nature of community, choosing here to instead reveal the inevitable camaraderie shared among a larger, heterogenous body.

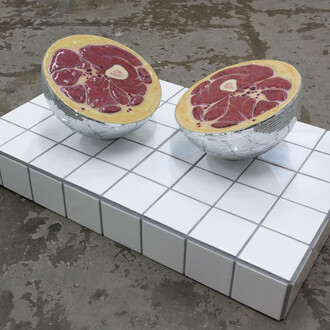

The sculptures in Weathering represent in part figures in Wang’s life—nail salon workers, restaurant cooks, deliverymen, drivers, and friends, among others. Forms recall animals and sculptural fragments of ancient statuary of colossal gods and phantasmagoric creatures while also citing readymade discoveries such as a crumbling cement monolith, garnished with two red apples, underneath the Queensboro Bridge. Wang likewise references the early stone work of Constantin Brancusi; the stainless-steel, bas-relief sculpture News (1938–40) by Isamu Noguchi on the façade of the Rockefeller Center; in addition to German academic figurative sculpture and state-sponsored monuments from an earlier era of the Chinese Communist Party.

Wang’s forms eschew austerity; the sculptures unify raw stone, found objects, and traditional materials associated with luxury. A thin sheet of oxidized, iridescent metal lines a gaping mouth carved in milky alabaster. Irregularly shaped pearls appear as flying seagulls. A form with pig trotter toenails clutches a gray pigeon feather. Placed on discrete plinths, sculptures confer with each other in an expansive formation that echoes the Big Dipper. In a related poem authored by Wang, he refers to the asterism as “a fingerprint on the sky,” reflected in the exhibition, from below. Invoking the Orion correlation theory, which claims the pyramids of Giza were constructed to align with the constellation, Wang establishes his own tender cosmology illuminated by abstracted mirrors and reflections, assimilating the looking glasses of contemporary life as well as more primordial surfaces—the smartphone screen, windows, and bodies of water—the gleaming luster of his sculptures alluding to that transparency. In a period of precarious coexistence, the artist seeks to extend the boundless capacities of hope and a foundational return to oneself.