The rabbits is 47 Canal’s second exhibition with Lewis Hammond. Including all new paintings by Hammond, the exhibition centers the eponymous motif—a symbol most often associated with fertility, but here laden with other, more ambiguous significations. In these works, Hammond continues his exploration of sociopolitical and spiritual tensions in our contemporary moment, joining compositional cues from the canon of art history with his own personal reflections. The rabbits follows the artist’s first solo exhibition with the gallery, Bludgeoned sky (2023).

In The rabbits, Hammond reconsiders the history of painting and its bonds with religious iconography and allegory. In his compositions, he quietly alludes to the anxieties and emotions driven by society’s fractures, as well as our diverting attempts to quell them. The artist queries the role of religion from past to present—in particular the powerful undercurrents of Christianity that nurture the development of ethnonationalism and chauvinism. In contrast, he considers his own upbringing as well as the essence of faith, hope, and belonging across borders. In his paintings Hammond traces a satirical and uncanny arc that can still speak to the conditions of humankind and our instinctual responses to fear. He often meditates on the work of Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), in particular the Spanish painter’s late pastoral scenes that depict all manner of ordinary characters—farmers, young children—with whimsy and gravitas.

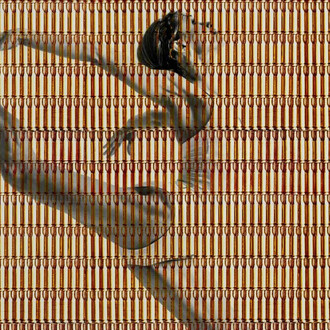

The paintings in this exhibition, as in his previous bodies of work, are moody, atmospheric, and elusive, befitting the crepuscular nature of rabbits. Hammond’s rabbits appear restless and alert, imbued with the spectrum and complexity of human interiority. The artist employs an earthy palette of traditional organic pigments such as lead whites and yellows, and as in his previous works, architectural framing devices structure his compositions and merge details of existing built environments like Juliet’s House, the thirteenth-century palazzo in Verona, and houses of worship.

These tight niches often box in Hammond’s subjects, magnifying disparate feelings of safety and unease. In Chained (2025), two rabbits copulate within an arched alcove as snowflakes fall. In Early paradise (2025), Hammond nests another alcove within a frescoed surface—one that recalls the garden room interiors once found in the ancient Villa of Livia in Rome, which features a gliding bird and a fruiting tree painted on the wall. Contrasting death and life, in Ye who grovels in the shade (2025), a single rabbit sits upright in front of a pile of human skulls, a memento mori that harkens back to the crypts in the catacombs beneath Paris. The enigmatic monk of Untitled or solemnis (2025), whose figure is drawn from Saint Dominic as portrayed in The mocking of Christ (1440), a fresco by Fra Angelico in the Convent of San Marco in Florence, serves as the lone human presence in the exhibited paintings, his eyes downcast as if in prayer.

The scenes of leporine pairs also summon the paradoxes and contradictions inherent in their symbology throughout religion, mythology, art history, and culture. Often symbolizing lust and fecundity, the rabbits in these paintings suggest the animals’ fervent proclivity for procreation in this time of crisis, their libidinal passions suspended in Hammond’s compositions. Though rabbits were often associated as the animal of Venus in ancient Rome, they were also depicted as symbols of virginity and virtue throughout the medieval era and the Renaissance. The rabbit has long represented good fortune and the moon, and would later become entwined with other connections: The etymology of “harebrained” reaches back to the mid-sixteenth century, a term describing the giddy and the reckless.

The artist’s earlier bodies of work rendered a range of interpersonal relationships and their attendant psychological and emotional intricacies, attempting to reconcile cultural, political, and moral crises. In his portraits and scenes of human entanglements, which assimilate older baroque or romantic palettes and styles, Hammond transforms faces and figures, often distorting them to a degree that—despite familiar visual references and tonal shifts—evades an easy absorption of accepted ideals. With The rabbits, he progresses this representation of shared unease, turning inwards towards spiritual material to reckon with an expanded understanding of disorder around us.