In his first institutional solo exhibition in Europe, Troy Montes Michie (b. 1985) draws on archives, memory, and cultural history to transform the galleries of Kunsthalle Basel into topographies of fragments. His practice navigates the friction between visibility and erasure, assembling what dominant narratives have sought to silence: personal stories and quiet griefs, together with cultural inheritances and histories of race, sexuality and class that endure in spite of erasure.

At the heart of Michie’s practice lies the archive, both personal and public. Family photo albums, intimate scraps, and print ephemera are not merely collected, but reimagined within the tradition of scrapbooking. Yet rather than resolve into coherent wholes, his compositions retain ruptures and absences. These interruptions are not gaps to be filled, but sites of tension where meaning is unstable and contested.

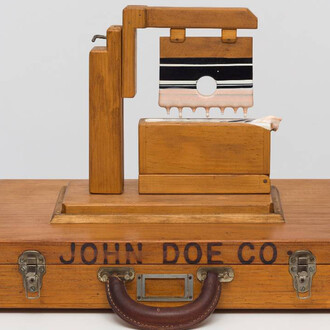

In his hands, the album is never only a keepsake; it becomes a vessel for fragile memory, where silence meets voice, and presence shades into absence. These processes take form in accordion-like objects; in textile collages cut and spliced; in assemblages that resist closure while preserving fragmentation. His use of domestic and found materials, reappropriated with care, points not only to personal inheritance but the politics embedded in everyday acts of labor, desire, and survival.

The exhibition’s title, The jawbone sings blue, evokes the quijada (Spanish for jawbone), a percussion instrument fashioned from animal bone. Rooted in the musical traditions of Africa and transported across the Atlantic via the transatlantic slave trade, its use in Afro-Latin and African American traditions became symbolic of the connection between life and death. Here, the jawbone becomes a metaphor, an object that vibrates with histories that refuse to be buried.

Michie’s spatial interventions avoid nostalgia, even as they echo the textures of home. They unfold as unstable thresholds where intimacy brushes against distance, and the familiar leans toward estrangement. By cutting and layering archival materials, the artist reveals how histories are constructed and how they might be reordered. What emerges isn’t nostalgia, but critique, an active reordering of history’s authority.

Troy Montes Michie invites us into a space of excavation, where memory, desire, and visibility collapse into one another. In this exhibition, the archive is not inert; it is woven, incised, veiled, and reanimated. What resides in the shadows of representation is as potent as what comes into view.

This body of work grows from Michie’s engagement with the fragmented archives of Richmond Barthé (1901–1989), a sculptor central to the Harlem Renaissance—the early-twentieth-century flowering of Black literature, music, performance, visual arts, and thought that asserted Black modernity and selfrepresentation in the face of racist exclusion. In Barthé’s incomplete scrapbook, with many of its images missing and pages left blank, Michie finds a mode of being that mirrors his own practice. The album is less a template than a point of tension: ruptured yet generative; irreducible yet insistently present. Rather than resolve those fractures, Michie positions them as sources of energy, asking not “What is missing?” but “What does this absence mean?”.

Visibility is composed

Michie’s interventions are about what is rendered visible, but they are also about how visibility is constructed through layering, stitching, and cutting. He works with simulated bronzed textures—a painted, paper-and-thread patina that recalls Barthé’s sculpture while remaining emphatically pictorial. This “bronze” is not metal but temperature and tone, a skin that shields and reveals.

He collages family photographs, erotic imagery, drawings, and archival materials, collapsing genealogies of intimacy and desire into the exigencies of queerness, race, and representation. Through engagement with the material, the archive is revealed as anything but static; it is living, vulnerable, and reactivated. Materials are not neutral surfaces but carriers of memory, lineage, and rupture. With each stitch, each cut, each repositioned fragment, the artist tends to what has been erased or neglected.

Some figures are lifted from pages that once staged and solicited queer desire for Black male bodies. This cladding does not repress erotic force; it redirects it. The subjects meet our gaze with probing intensity, confronting and withholding at once, undoing the terms under which their images were first consumed. In choosing what to carry forward, Michie performs a painterly act of selection: visibility is composed, not simply revealed.

Fragments as method

At the center of the first gallery, an accordion-like structure unfolds. Page by page, photograph by photograph, the sequencing suggests narrative, and yet that narrative resists chronology. Time here is rhythmic, contingent, untethered. Around this gesture, discrete objects accumulate as tactile echoes in the exhibition. A shirt poised to be worn, a chair on which sits a photograph instead of a body, and skeletal armatures that resemble clothing racks all hover between the trace and the manifest. Their presence is strategic: in these in-between spaces, absence takes on form, and presence becomes a question.

The exhibition layout opens perspectives in which the act of looking becomes self-aware, and viewers’ paths begin to mirror the very ways in which history is constructed. Like the differing narratives through which histories are told—and by which disorientation often arises—the spaces, too, evoke that sense of unsettlement. They offer interruption rather than clarity, fragmentation rather than familiarity. Through windows and across thresholds, visitors glimpse works partially concealed behind walls. As viewers move —approaching and retreating, pausing and returning— looking becomes choreographic. The path of the body mirrors the editing strategies of the collages: each fragment stands apart while remaining part of a shared rhythm.

Moving through the exhibition, the viewer becomes aware not only of other lives but also of their own act of scrutiny. Gaps between images, excised shapes, and layered pages carry tension. These heavy silences —registering in stories not told, bodies not shown, and gestures deferred—point to collective grief but not despair, and they demand persistent attention. Within a contemporary climate that too often prefigures Black masculinity as a threat, the works refuse legibility on imposed terms by multiplying Black and Brown subjects chromatically and compositionally and by redirecting desire rather than displaying it. What emerges is not the articulation of a singular loss but a cultural condition: the ambient sorrow of histories that remain unsettled by systems of exclusion and marginalization.

In The jawbone sings blue, mourning is a methodology. It does not provide closure but sustains a relational field of presence and absence, clamor and silence, fragment and whole. Absence resonates, demanding to be heard.