Kunsthalle Basel presents a new commission by Coumba Samba (b. 2000), an artist whose practice consistently probes the aesthetics and politics of institutional power, control, and the residues of colonial and state violence. She often extracts tones from national flags, personal archives, and state apparatuses such as domestic interiors or official insignia, turning them into fields that read as formal but are saturated with historical significance.

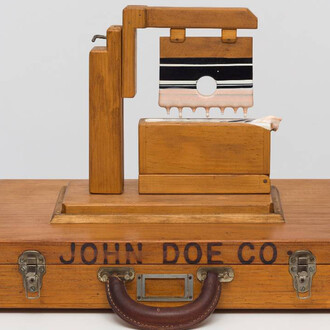

Wild wild wall is a large-scale sculptural installation: 176 square steel posts span the back wall of Kunsthalle Basel, each separated by four inches (10.16 cm). This spacing was first introduced under George W. Bush and later adopted by the Trump administration in the construction of the Mexico–U.S. border wall. What first appears as a minimalist composition of black and gray stripes reveals itself as a translation of the desaturated tones of the U.S. border patrol badge of honor and replicates the chromatic inscriptions of such emblems. This variegated act exposes how seemingly neutral colors and forms are in fact imbued with histories of violence, exclusion, and control.

“Tear down this wall!” echoed across the Brandenburg Gate from West to East Berlin in 1987, posing a symbolic moment of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall, erected with the tacit approval of the Soviet Union, stood from 1961 until 1989 as one of the central markers of ideological division. This historical dissonance gave the United States government a narrative framework to consolidate global alliances and strengthen immigration policies. Beginning in the 1980s, with the advent of the modern US refugee resettlement program, most of the three million refugees were admitted from Vietnam, Cuba, or the former Soviet Union. During this period, the term “refugee” in US discourse largely became synonymous with “a refugee from communism.” By contrast, Haitian refugees were described as “a serious national problem.” Asylum policy was thus determined more by geopolitical affiliation than by individual experiences of violence or persecution. By the 1990s, significant federal funding began to be directed toward the construction of a wall along the Mexico–U.S. border.1

In their book Against borders, Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke de Noronha describe nationalism as “colonialism eating itself into the present.”2 They argue that nation-states are relatively recent political formations shaped by the legacies of empire, colonialism, and slavery. Similarly, Samba approaches borders not as neutral demarcations but as instruments of classification—tools that sort and stratify populations through cultural and biological markers, reinforcing racialized systems of exclusion on a global scale.

Samba’s research focuses on demonstrating how borders, constructed largely by dominant powers, serve to reinforce ideologies of separation and to distin guish a supposed order from the “chaos” imagined to lie beyond. In her view, the border’s harsh terrain and authoritarian dominance by patrol guards operating with little oversight make the border a sort of wilderness, with minimal scope for justice. Historical and political developments of border fortifications, their symbolic resonance, and the immigration policies form the framework within which Wild wild wall is positioned. Samba’s installation posits these complexes in a spatial and visual register.

By translating these ideas into the language of form and color, Coumba Samba foregrounds how historical power relations persist. In Wild wild wall, the friction between national signifiers and lived reality becomes clear in the artist’s own words: “Four inches, just enough to touch the air on the other side.”

Notes

1 See Eileen Truax, We built the wall: how the U.S. Keeps out

asylum seekers from Mexico, Central America and Beyond.

London/New York: Verso, 2018.

2 Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke de Noronha, Against borders:

the case for abolition. London/New York: Verso, 2022.