Sometimes

silence is felt,

and in that instant

light becomes

infinite,

and in the depth

of every word

resounds

the essence

of who we are.(Giuseppe Ungaretti)

In a world where reality often intertwines with the intangible, reflections on the human condition arise that transcend the everyday. Dreamlike experiences, those fleeting moments that transport us to landscapes of reverie, reveal the hidden and deeper layers of our existence. In the dance between the tangible and the metaphysical, we find ourselves on a constant journey of search and connection, yearning to understand the sacredness of our being. In this exploration, the painting of Jem Perucchini (Tekeze, Ethiopia, 1995) becomes a mirror of this search: it embodies introspection and spiritual longing in a figurative representation.

Perucchini, with Ethiopian roots, brings with him a rich cultural heritage imbued with Byzantine influences that have shaped the artistic tradition of his homeland. Ethiopian painting reflects a constant dialogue between the sacred and the everyday in its vibrant frescoes and deep symbolism. This heritage combines with his education in Italy, where he studied at the Brera Academy, allowing him to merge elements of his native culture with the techniques and concepts of Renaissance art history and Italian Novecento. “I was born in Ethiopia, a country of extraordinary historical richness and connected to the West. I grew up and was educated in Italy, a place of great significance in the history of art. These two aspects of my life converge in my work.” Thus, his work becomes a crossroads where the spirituality of Ethiopian iconography intertwines with Italian art history and modernity, creating a unique visual language that invites contemplation and reflection on the human condition.

A bridge between cultures

The art of painting is not just a technique; it is a reflection of the human soul, a search for the beauty that resides in truth. Through light and shadow, the painter brings his visions to life, creating a universe where the divine meets the everyday.

(Leon Battista Alberti, “De pictura”, 1435)

Italian art, throughout the centuries, has experienced a profound rediscovery of classical antiquity and humanism. Artists such as Piero della Francesca (c. 1415-1492), Fra Angelico (1395-1455), and Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516) were essential in the development of techniques that emphasized perspective, anatomy, and the use of color to create depth and realism. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), in his treatise on painting, highlighted the importance of these elements, concepts that have been adapted by contemporary artists like Perucchini, integrating figures from diverse cultural heritages into classical scenes, fostering a dialogue between the past and the present.

As Italian art moved through the 20th century, it sought to reinterpret classical tradition in a contemporary context, with artists like Felice Casorati (1883-1963), Carlo Carrà (1881-1966), Adolfo Wildt (1868-1931), and Medardo Rosso (1858-1928), who combined this tradition with modern styles. This movement promoted figuration and monumentality through a synthesis of the ancient and the contemporary.

Italian colonialism in Africa, particularly during the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, left a significant mark on painting, as art was used as propaganda to legitimize its presence. This political context influenced artistic production, promoting ideals of grandeur and power. Artists of the Italian Novecento operated in an environment where art was expected to serve the state, reinforcing fascist ideology through the exaltation of a glorious past and a heroic present. Margherita Sarfatti (1880-1961), an art critic close to the regime, advocated for a return to classical and monumental form, free of unnecessary ornamentation. This aesthetic approach echoed colonial policy, imposing in visual representations a narrative in which Western civilization was superior, to be manifested not only in painting but also in architecture and decorative arts, seeking a synthesis of pure forms and harmonious compositions that evoked the grandeur of the Greco-Roman past in a contemporary imperialist context.

In this complex historical fabric, the concepts of Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), who explored the intertwining of stories and iconographies across various cultures, myths, and archetypes, gained relevance by providing a theoretical framework that allowed for understanding how artistic narratives reflect shared human experiences, not through the imposition or superiority of some cultures over others, but by stemming from the same original magma. “The stories we tell are an echo of shared human experience,” writes Campbell.

Thus, Jem Perucchini’s work uses the Christian iconography of the Renaissance, with that aura of sacred intimacy, rendered with pictorial techniques ranging from pointillism to sfumato and a framing devoid of perspective, giving his works an altar-like appearance. He portrays Black people dressed in batiks or wax fabrics from the purest African textile tradition, without any political or ideological intent, but with the sole purpose of integrating diverse cultural heritages and offering a new narrative that transcends the dominant discourse through a conversation that pursues that ontological meaning central to Campbell’s work. “The interaction between cultures, archetypes, Renaissance painting, the neurological processes motivated by images that provoke emotions and visions are fundamental aspects of my painting.”

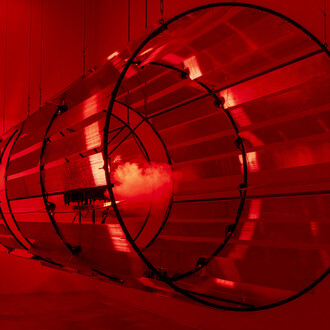

Rebirth of a Nation, both for its public nature and its multiple meanings, is a large mural created for the Art on the Underground initiative. Located at the entrance of the underground in the iconic London district of Brixton, an “amalgam of cultures and histories,” as the artist himself has defined it, and known since the 1940s for its high percentage of Afro-Caribbean population, it stands as a powerful artistic statement celebrating the rich and multifaceted history of the neighborhood, while also being a tribute to “the little-known past of a community and the hope for a more egalitarian and inclusive future.”

Through a display of intense colors and evocative figures, Perucchini alludes to the cultural heritage of Brixton, a neighborhood that transformed into a refuge for post-colonial migrants after World War II, whose indomitable spirit of resistance against racism and Western social conventions is one of its defining characteristics. The title of the work is already a statement of intent by making a direct reference to The birth of a nation (1915), a film directed by David W. Griffith, whose “clearly racist and misleading intention about the formation of the United States […] struck me for its glorification of its intentions.” No less intentional is the relationship of its central figure to the Ivory Bangle Lady, as the remains of a Black woman of certain status in Roman Britannia are known, found in a 4th-century tomb in the center of York. Both the title and the iconography correct the historical narrative to point out the much older origins of the Black community in Britain and those excluded from American history. This mural is a secular altar that awaits us in a daily place, a visual hymn to the diversity, memory, and resilience of Brixton, a celebration of its unique identity, and a challenge to society to, in its effort to look forward, not forget its roots.

Transcending the visible

I illuminate myself with immensity

(Giuseppe Ungaretti, “Morning”)

Perucchini’s works reflect a deep understanding of visual narrative by integrating elements that evoke universal archetypes. Thus, not only the Black figures but also symbolic elements such as the staff, the sphere, chess, the sun, along with the lost gazes of his characters and the gestural language of their hands, resonate with the richness of the everyday. This approach reminds us that despite our differences, we are united by the stories we tell and the truths we seek.

The Black figures are not only representations of individual interaction, but by acting as a link between different narratives and experiences, they subvert these stories and offer a new perspective on the interconnectedness and complexity of human experiences. The artist layers meaning into his work, inviting the viewer to reflect on identity and belonging in a world dominated by the narratives of a center that prefers to forget its internal and external margins, its peripheries. In doing so, the artist not only honors his Ethiopian heritage but also highlights the importance of recognizing and celebrating the richness of all cultures, inviting us to reflect on the choices we face as human beings sharing the same space. “I would like my work to be understood and appreciated by people of different backgrounds and cultures. I stand for art as a tool for integration, and the fact that I portray figures of color is not a choice, not an expressive intent. It’s much simpler: I think it’s normal to imagine and represent them as I am, anything else would be absurd.”

In this pursuit of truth, the intense gaze of Jem Perucchini’s figures, often charged with emotion and depth, can be interpreted as a longing for connection with the divine, with the transcendent, where the hero’s journey resonates, experiencing visions or revelations that guide him along his path. This visual connection emphasizes that spiritual searching is not just an internal journey but an aspiration to connect with something that transcends everyday reality.

Like in Ethiopian mural paintings, where the characters look into the infinite, Perucchini’s figures invite the viewer to contemplate their own search for meaning. These gazes, directed toward a point that may be both internal and external, engage in dialogue with the viewer, creating an interaction that transcends the physical and delves into the spiritual.

Just as the gaze, the mannerism of the hands transcends simple physical representation to become a complex language that articulates the emotions and narrative of the figures. Each gesture is intentional and has been carefully crafted; it carries symbolic weight that invites interpretation. The hands seem to converse with each other, positioned in attitudes of waiting, offering, or holding back; they communicate moods, longings, and internal tensions. This gestural language, a nuanced form of non-verbal communication, like the gazes, establishes a bridge with the viewer, turning them into vehicles of meaning that articulate not just what is said but what is felt, reminding us that it is often in what is left unsaid where the true essence of our humanity lies. Like in the poetry of Giuseppe Ungaretti, Perucchini’s figures seem to long for that same relationship with the divine, seeking light in darkness to reach the sublime.

The individual and the universal

You, in the deep light,

oh, confused silence,

you persist like an angry cicada.(Giuseppe Ungaretti, “The meditated death”)

The attitude, introspective gazes, and gestures suggesting an untold story establish a dialogue in Perucchini’s work between the individual and the universal, echoing historian Aby Warburg’s (1866-1929) idea that art acts as an echo of shared experiences.

Warburg emphasizes the importance of images as vehicles of collective memory, suggesting that they not only represent specific moments but also possess a metaphysical dimension. In Perucchini’s work, this dimension is manifested in how the figures seem to exist in a liminal space where the material and the spiritual intertwine. By integrating both specific and archetypal cultural influences, Perucchini suggests that the search for meaning is an eternal process, part of the human experience since the beginning of time.

Thus, each painting becomes a fragment of a larger narrative. This historical and metaphysical continuity is reflected in the use of light, color, and composition, which not only capture the essence of the present moment but also evoke a sense of transcendence. Perucchini’s painting is a metaphysical journey, and in this universe of forms and colors, textures and finishes play a crucial role, being essential in creating an evocative atmosphere with patterns and roughness that highlight the sacred —a heritage of Byzantine and Ethiopian traditions— and suggest a wide range of tactile sensations. His carefully chosen palette allows the interaction between color and surface to enrich the viewer’s visual experience.

The metaphysical aspect of Perucchini’s painting unfolds as a hymn to existence, where every stroke and color resonate with the echo of a shared universe. The Black figures integrate diversity into their narrative, like threads in a living tapestry woven by interconnected stories. In this creative space, art becomes a vehicle for transcendence, inviting us to look beyond the visible and explore the essence of who we are, in a journey toward representing the human condition while also invoking the eternal, a reflection of the soul in its search for meaning and connection with the vast cosmos of human experience.