After 30 Conferences of the Parties—governments of the world coming together to solve the climate crisis—it is time to recognize that governments cannot and will not act decisively and on time. Not so long back, many of them were denying the existence of the crisis, but now, barring one prominent fossil fool sitting in Washington, DC, at least such denial is no longer possible, given the widespread evidence of its existence and impacts. But if we ever needed proof that simple knowledge of a problem does not necessarily lead to action to solve it, all these expensive COPs are surely enough.

Continued power games and profit-making

The problem does not lie in a lack of knowledge of the crisis, nor in an inadequacy of solutions. The problem lies in the unwillingness of powerful actors, including governments and corporations, to act. Sunk in the depths of capitalist profit-making and statist power games, steeped in long histories of colonialism, patriarchy, and a form of rationalist modernity that has given us the illusion we are separate from nature and can do what we want with the earth, these institutions are simply not fit for purpose when it comes to building pathways out of the climate crisis. Or, for that matter, the other crises intersecting with it, of inequality and discrimination, war and genocide, epidemics of both poverty and affluence, and more.

There was some hope in some civil society circles and in some governments (those few who truly want urgent action, such as Small Island States) that COP30 in Belem, Brazil, may achieve some breakthroughs. This was because of its location right next to the Amazon forest (it was widely labelled as the ‘forest COP’) and in a country whose president seems to be serious about climate action. But if anything, this COP appears to have backslid even from the cautious progress made in earlier COPs, for instance, in the matter of phasing out fossil fuels and curbing deforestation. Neither of these finds mentioned in the Belem agreement.

If one wants to look desperately for some positive news, one can mention the inclusion of ‘just transition’ in the Belem Action Mechanism—after many years of advocacy by trade unions1 and civil society groups, this acknowledges the need to seriously integrate the interests of working-class populations affected by the transition to climate-friendly economies. An increase in finances available to so-called ‘developing’ countries for their transition has also been welcomed. But these are minor compared to the kinds and scale of urgent action needed in a scenario where we are apparently already locked into an increase of global average temperatures of 1.5 degrees, where all the Nationally Determined Contributions (action plans) put together do not amount to anywhere near the reductions in emissions needed, where hundreds of millions of people are in urgent need of adaptation measures, and where thousands of non-human species are already being adversely impacted.

The ones who have really gained, again, are corporations and governments that continue to profit from climate-unfriendly activities such as promoting fossil fuels and those who are investing in so-called ‘green economy’ or ‘climate transition’ projects and processes. Evidence of the disastrous impacts of such transitions is visible across the world, especially in the global South—large-scale mining for lithium for electric vehicles, mega-renewable energy projects grabbing huge tracts of terrestrial and marine areas crucial for biodiversity and for the livelihoods of pastoralists, farmers, and fishers, expansion of plantations for biofuels into natural forest and grassland areas, and so on. Nature, and communities dependent on it who have never been responsible for the climate crisis, are becoming ‘sacrifice zones’ for this so-called transition.

One of the big announcements at COP30 was the launching of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility2 (TFFF) proposed by Brazil. Aiming to mobilize several billion dollars in investments, the TFFF is promoted as an effective way of protecting forests and has been welcomed by several governments and civil society organizations. Critics, however, point out that this signifies a dangerous new way of commodifying and commercializing3 forests and could lead to even greater control over forests by powerful government agencies and corporations, most likely at the expense of Indigenous peoples and other communities living in them.

Where, then, lies the hope?

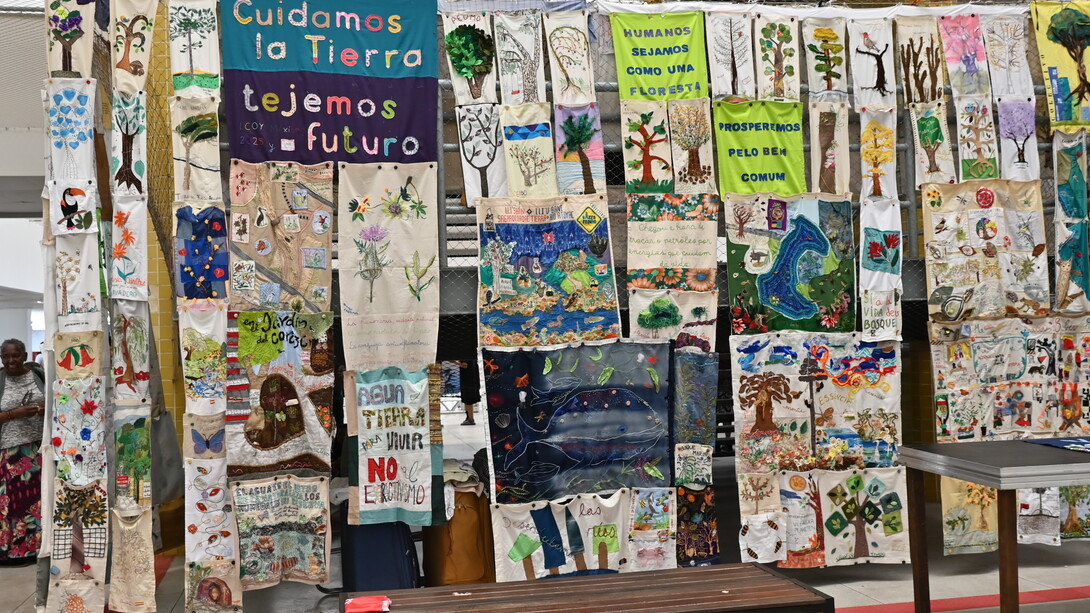

On 15th November, in the middle of the COP30 period, people’s movements from across the world took out a march. The number of participants is unclear—organizers say 70,000, but while I think that’s an exaggeration, it was certainly very impressive. It was an inspiring, soul-lifting spectacle, with a bewildering spectrum of peoples, colors, costumes, languages, dances and music, slogans, and more on display. Sprinkled through the march were Indigenous peoples, especially from Brazil and Latin America but also many from elsewhere, their headgear, body painting, and energy palpably distinct from the others. Also prominent were leftist movements and organizations, who were among the main organizers of the Cupula dos Povos (People’s Summit)4, which brought together hundreds of formations from across the world in events outside the official conference.

While the mobilization and voices of Indigenous Peoples were intersecting with those of the People’s Summit, they also had their independent space (Aldeia COP) and their own separate mobilization. I was not able to follow much of their activities, but they were present both in the official spaces (e.g., the so-called ‘Blue Zone’) and as pressure from outside. The latter included two dramatic actions, one of invading the official venue as a protest against being largely excluded from official decision-making spaces, and the other of blocking the venue’s entrance till the COP President came out and assured them of action on their demands. One immediate outcome of such actions and the significant Indigenous presence was the recognition of the territorial rights of Indigenous Peoples in 14 territories of Brazil, including over 2 million hectares of the Amazonian forest.

This brings me to what, for me, was the most important realization. Not a new one, but reinforced here: that action on climate and other related crises is mostly going to come from grassroots mobilization, from ground action by Indigenous peoples, other local communities, mass movements, and civil society, and from enlightened local authorities who are influenced and guided by such movements or by political actors who really care. Not so much from national governmental and international institutions made up of such governments. There is the exceptional action by such institutions that makes a difference, but usually this too is spurred on or forced by people’s action, such as Brazil’s recognition of Indigenous territories during COP30.

The missing element

For some of us who were representing the Global Tapestry of Alternatives5 (GTA) there, our focus was much more on grounded power, rather than trying to influence the official process. One of our events was on ‘Radical Democracy and Climate Justice: The Missing Debate at COP30.’ It was a small but diverse group that gathered, co-organized by GTA, Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN), Well Being Economy Alliance (WEAII), ICCA Consortium, War on Want, Academy of Democratic Modernity, Global Forest Coalition, and World Assembly of Struggles of WSF. While coming from varying areas of work and focus, participants agreed that we needed to work much more on documenting, supporting, enabling, and inspiring forms of radical democracy, autonomy, self-determination, and earthy governance in which the most marginalized sections of humanity, and the rest of nature, have a central voice.

This event and other inputs by GTA to civil society sessions at COP30, including at various events organized by the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature and the International Tribunal on the Rights of Nature, built on two previous gatherings that it has helped organize in 2025. In February, about 20 Indigenous Peoples and other local communities, and several civil society organizations, mostly from the global South, came together in Port Edward, South Africa.

They shared experiences of radical, grounded democracy6, autonomy and self-determination, and attempts at localizing and democratizing the economy, food sovereignty, assertion of cultural and political identity, and more (while also dealing with internal gender and other inequities). In June, another diverse set of participants from Indigenous people, local communities, civil society, and academia gathered in Sydney, Australia, for storytelling and building greater collective understanding of ‘earthy governance and interspecies justice.7’ The crucial message was that the rest of the planet, beyond humans, needs to be part of our decision-making.

The session in Belem, though much smaller than these two, was part of the series. Why did we give it the subtitle ‘The Missing Debate at COP30’? Because of the need to challenge liberal, electoral ‘democracy’ centered on the nation-state, which has for too long been promoted as the most enlightened form of political governance. Even much of civil society (including, or especially, the conventional Left) appears to have accepted this, which explains its predominant focus on appealing for or demanding policy measures from governments and intergovernmental institutions, or the enormous energy put into trying to get progressive or revolutionary parties into power.

But many Indigenous people’s movements, local community assertions, some urban collective movements, and many from the new Left, feminists, Gandhians, activists of the Kurdish and Zapatista movements, and others have questioned this. They point to the repeated failures of nation-states, including most of those led by parties that have emerged from grassroots struggles. Podemos in Spain, social democratic parties in other parts of Europe, Syriza in Greece, various leftist parties in Latin America, and so on, have promised much, but in the end not transformed society in any fundamental way, even though some have achieved much better welfare and rights-based measures than others.

Elsewhere I've written about the problems8 inherent to liberal ‘democracy’: the tendency to centralize power, get alienated from ‘ordinary’ people, and compromise to be able to stay in power (Brazil at the moment being a visible example). Combined with the continuing reliance on the extractivist and globalized model of ‘development’ and an education system that brainwashes citizens into being pliant followers, the modern nation-state (capitalist or socialist or anywhere in between) is inherently undemocratic and ecologically unsustainable.

Strong as it is and radical in many of its elements, the People’s Summit Declaration9 does not question the nation-state as fundamentally anti-democratic or the need to go beyond current boundaries with a biocultural or bioregional approach10 that respects natural and cultural flows.

Grounded action shows the way

In 2021, a study showed that11 resistance by Indigenous peoples to fossil fuel expansion in what are today called the USA and Canada “has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least one-quarter of the annual … emissions” of these two countries. Wherever such communities or civil society actions have helped stave off deforestation, destruction of grasslands, and draining of wetlands—and there are hundreds of examples of these across the world—it is helping in avoiding or mitigating causes of the climate crisis.

Beyond this, there are also innumerable examples of constructive alternatives to destructive development—food sovereignty by small-scale peasants, pastoralists, and fishers using ecologically sensitive methods; energy sovereignty by collectives using decentralized renewable energy as well as restricting runaway energy demand; climate-sensitive construction combining ancient and new architecture; decentralized water harvesting and wetland conservation; and more. Thousands of examples of ‘territories of life’12 have demonstrated that communities can be the most effective conservers of natural ecosystems and wildlife populations. Increasingly such peoples are also advocating and demonstrating biocultural or bioregional pathways that go beyond nation-state boundaries, such as the Amazon Sacred Headwaters initiative13.

These and other pathways are contingent on, or enabled by, movements of radical democracy and autonomy. Decision-making on the ground, where most or all people have the capacity and the right to participate, and where the non-human is also at the core of people’s vision—what I have called Radical Ecological Democracy14 (RED)—is crucial to any meaningful strategy for dealing with the climate crisis. Intergovernmental institutions are simply not suited to enable such a fundamental transformation in democracy, though they may, rarely, take steps that at least reduce the hurdles towards such a transformation. And so, even as we need to continue trying to make nation-states and their international institutions accountable, as civil society, we need to put much more energy into enabling the grounding of power.

Lessons from existing initiatives of RED (and various similar approaches, including swaraj, Zapatismo, democratic confederalism, sumac kawsay, buen vivir, ubuntu, etc.) can be exchanged, more such initiatives stimulated and supported, and a non-hierarchical global alliance established. In the long run, the goal could be to even dismantle nation-state boundaries towards much greater respect for natural, cultural, and economic flows (biocultural regions) between the peoples and ecosystems of the world. There is no reason why the nation-state model cannot be replaced by governance through grounded forms of democracy, federating across large regions in ways already demonstrated by the Zapatistas, the Kurdish Rojava, and other revolutions.

The planet and all the wonders of life we still have with us need such a fundamental shift, beyond an infinite number of intergovernmental COPs that achieve little, towards a Confluence of Peoples, the real COPs.

References

1 Belém Action Mechanism on Just Transition: A breakthrough for workers amid major failures at COP30.

2 Tropical Forest Forever Facility.

3 TFFF: A False Solution for Tropical Forests.

4 Peoples’ Summit Towards COP30. (n.d.). Home.

5 Global Tapestry of Alternatives. (2025).

6 Reclaiming Power: The Path Towards Radical Democracy and Collective Liberation.

7 Earthy Governance and Interspecies Justice Confluence - 16-17th June, 2025, Sydney.

8 Elections, power, and the illusions of choice.

9 Peoples’ Summit Towards COP30. (2025). Final declaration from People’s Summit Towards COP30.

10 Bajpai, S., Crespo, J. M., & Kothari, A. (2022, March 7). Nation-states are destroying the world. Could ‘bioregions’ be the answer? openDemocracy.

11 Indigenous Environmental Network & Oil Change International. (2021). Indigenous resistance against carbon (PDF report).

12 ICCA Consortium. (n.d.). Home.

13 Cuencas. (n.d.). Home.

14 Radical Ecological Democracy. (2018, October 2). RED Conversations Series – The emerging idea of “Radical Well-Being”.