When gallerist Bruno Brunnet invited architect Arno Brandlhuber to design an architecture exhibition at Contemporary Fine Arts gallery in Totengässlein in Basel, Brandlhuber declined, saying, “It would be better to exhibit what is already there.” The gallery space should not serve as a backdrop for an exhibition – instead it should be the exhibit itself. The topic should not be a reference to architecture that has been planned or realized elsewhere, but rather the question of how architecture as such can be exhibited. This approach, which is still quite new in the field of architecture, ties in with the artistic critique of institutions developed in the realm of art since the 1970s, i.e., the idea that art critically reflects on its own conditions.

During a visit to the site, a mural in the gallery’s courtyard stood out. Painted in 1979 by Ernst Georg Heussler (1903-1982), it had been commissioned by the building’s owners, Gerda and Donald Kanitzer, who ran a fur shop on the premises from the early 1970s and now live in the apartment above. (An older, heavily faded fresco by Heussler adorns the facade of the building.) When the building was converted into a gallery in 2023, the large window openings facing the courtyard were covered. The mural could only be seen from a side room. To show what is there, the view of the courtyard is now being reopened.

The mural in the courtyard, painted in bright blue and green tones in the late Cubist style, depicts a lantern typical for Basel’s Morgestraich parade, which is carried through the city at the start of Carnival. The subject of the lantern is the Fall of Man. Surrounded by animals, Eve offers Adam the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge (Gen. 3:6). In the interview, Gerda Kanitzer explains that the figure looking through a peephole into the lantern at the paradise scene is an allusion to a peep show that was banned in Basel in 1979 but had been flourishing in Zurich since 1977 as the “Stützlisex.” The figure floating above it, behind the moon, alludes to Paul VI, known as the “pill pope,” an opponent of contraceptives. What the people of Basel were denied could be admired in the backyard of the fur shop.

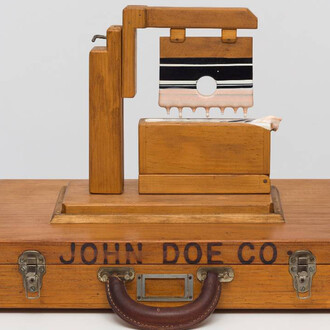

In 2024, Sarah Lucas’ sculpture Jane B (= Jane Birkin, who sang the global hit “Je t’aime… moi non plus*” with her partner Serge Gainsbourg in 1969) was displayed on a turntable in the gallery’s shop window. “Never before had so many people stopped in front of the window,” recalls Gerda Kanitzer. For the current exhibition, the shop window is covered with a blind designed by artist Constanze Haas, with a peephole cut into it. When looking through it, you can see inside the gallery, the desk that normally remains hidden in the background. Exhibiting what is there also means showing the gallery’s operations, putting former gallery director Katharina Hajek and current director Flavia Senn in the spotlight. When they are not using the computer, a short film by filmmaker Severin Bärenbold runs instead of a screensaver: the interview with the Kanitzers.

The walls of the gallery remain empty during the exhibition. The focus is on Heussler’s artwork, which, according to the Kanitzers, he was motivated to create because he was “bothered by the empty wall.” Since a gallery primarily serves to sell artworks, four artworks are displayed next to the worktable, all of which relate in some way to the depiction of paradise: Peter Doig’s painting Daytime astronomy (1996), his drawing Gauguin (ca. 1983), Cecily Brown’s painting Untitled (#102) (2010), and Sarah Lucas’s photograph Polaroid bunny #3 (1997) are all non-saleable loans from the private collections of Nicole Hackert and Bruno Brunnet. If desired, the works can be temporarily hung on the wall.

What does a building know? Or, to put it another way, what meaning is manifested through spaces and architecture? Art historian Charlotte Matter recalls Charles Baudelaire’s statement, Qu’est-ce que l’art? Prostitution and the accompanying equation of sex work, commerce, and art. Open for Paradise is not an exhibition about this topic. Rather, it creates a spatial connection between voyeurism and desire, sex work and art dealing, peepholes and empty walls, actors and observers. The exhibition does not assert anything, does not invent anything, but rather makes visible what has been found: “Show, don’t tell!” It is an encouragement to change perspective, to produce new meaning, and – to stay with the image of the story of creation – to open one’s eyes.

(Text by Philip Ursprung)