Among the flowers: a pot of wine

I drink it alone---with no one

I raise it to invite bright moon

With Moon, my shadow, and wine: we are three in tune.(Li Bai [701--762])

Kate Oh Gallery is pleased to present The poet of the urban fabric by Jimin Bae, on view from November 4 – 9, 2025. Reception Date: November 6, Thu, 5 -8Pm.

Entering an exhibit of Jimin Bae's ink works is like wandering along a November sidewalk in a quietly sleeping city, where the crafty winds have cleaned the paved streets of every bit of chaos, where boreal lights seem to have suffused with an unearthly sheen of crystalline greyscales. This is one dreamless world from which the busy scuttling of scholars has fled, as if through an alternate tunnel of a philosophical exile—the graduated reduction of complexity to maddening clarity. It is here, therefore, that the wandering connoisseur may be subjected to the initial shock of uncanniness, albeit delectably transient, to imbibe ultimately the more succulent realization that it is neither quite the common Eastern ink painting nor the postmodern melee of Western urban landscape that they're looking at, but a blanketing liminal space where the thesis and antithesis of any argument have lost the meaning of coherence and been transformed, as if by a sweep of the autumn wind, into the heights of lonely transcendence.

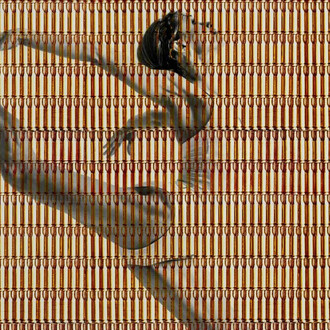

Indeed, the ink that the artist uses recalls to my eyes not so much the appearance of ink but the delicate wrapping of silk, fabric, or some other gently adumbrating material, perhaps one that is trying so hard to withstand the ravages of time that it has willingly evolved from an exterior layer to embrace the very interior that it envelopes, almost like a protective gauze, which has been on the thumb for so long that it has fused with the skin. These layers of greyscales, these protean transfixations of unitary color, these casual markings of a hyper-intentional mind—of crying dots and sighing strokes, at once simple, autonomous, as well as intercorrelated like the hypotheses of a complex series of debates—do not want to be removed. Thus, touch them with your attention, and they will no longer appear painted. They no longer appear as the traces of a brush. Like the stamps that mark the postage on a very special package, they wish to adhere; they wish to be considered as a part of the whole. And so, a letter in which every line reads like a novel has just been opened in front of us.

But caution is to be exercised, for it would be a letter we cannot understand without knowing its origin. Here we are reminded to take a closer look at the history of this particularly fascinating medium: the ink painting is called Sumuk in Korean, and its tradition is unearthly, resonant, having traveled from China during the Three Kingdoms period (4th–7th century) and matured uniquely on the Korean peninsula. While indebted to Chinese literati works, Korean Sumuk came to sing with its own voice. It has evolved into a genre that is less about scholastic demonstration—certainly much less about the imitation of reality—and instead, a painting of Sumuk assumes a solitary discourse with nature, with remoteness, and with lived experience that has been abandoned and perhaps reanimated into something that resembles a glimpse of immortality. Just like the mystical Chinese poet Li Bai (701–762), a practitioner of Sumuk may often prefer to live and work with spontaneity. They wield their instrument like a hermit who exercises with the utmost minimal means: brush, ink, silk, and water—simple but never easy to handle—so that every stroke becomes a crystallization of internal effort rather than an imitation of external form. Veritably, in the deft hands of a master, black ink with its infinite range of greys explodes into a canvas not of depiction but of metaphysical dialog with oneself through the world.

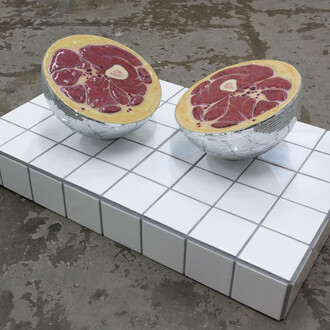

So, it is from this auto-communicative tradition that Jimin Bae has stepped into our exhibit in the intimate space of Kate Oh Gallery. To the already subtle layers of Sumuk, Jimin adds even more layers of evanescence: stitching fabric and other substrates on Korean paper, Hanji, recasting fabric and paper into an urban world. This makes it multi-dimensionally complex, like the layers of shadows superimposed on one another under the most subtle illuminations. Each painting could be one camera obscura, receiving light through a ghostly little pinhole, to recreate in a dimmed room an entire landscape of a city. And thus, slowly, like a cup of wine, it is to be tasted and pondered, together with gallery friends as well as in solitude.

(Text by Benjamin Alexander)