Globalization has spread radically, since the most powerful and valued areas, such as finance, information, communication, the attention industry, are all based on immaterial flows, characteristic of this digital revolution. The virtual flows know no borders, and the global organizations like the UN were built for another reality. In this chaos, social and solidarity economy organizations can use these same technologies to build a collaborative global network.

This is becoming a small planet, and fast. When my parents moved to Brazil in 1951, we went by ship; it was some enterprise. And it felt mysterious. I just participated in a meeting in San Sebastián, in Spain, with hundreds of people from 30 countries, building an international collaborative network of social and solidarity economy, an initiative headed by the Mondragón cooperative. India, Mexico, Senegal, Brazil, Canada, UN, ILO, OECD, Oxfam, ministers from different countries…you name it. The common denominator was people fed up with the corporate International pushing us down the drain through climate change, deepening inequality, financial chaos, biodiversity decline. Unrestricted profit maximization in the hands of global corporations is a disaster. And there is no global corresponding regulation capacity.

We do have international organizations, certainly, with represented nations, 193 in the UN. But this is a global governance structure representing a particular situation eighty years ago, a colonial world, so many nations destroyed, and it has become woefully inadequate nowadays. The United States was the glorious, unique power at the time, with veto power in so many instances, including the IMF and the World Bank, and with the dollar as a global currency monopoly. This is all changing, and we are facing challenges these institutions were not meant to face. And as the so-called “slow-motion catastrophe” deepens, anxious people, NGOs, local governments, personalities, even businesses, are searching for new forms of cross-territorial organization. With the new technologies, the idea of space has changed. Manuel Castells, with his The Rise of the Network Society, drew the main lines, but it is accelerating.

I am not aiming here at listing the disasters; those charmed by the drill, baby, drill are beyond our command, but the vast majority in the world, and particularly you who are interested enough to read this paper, know very well the dimensions of the challenges, the threats we are facing as humanity. Stimulated by the meeting I mentioned, by how quickly we can bring together people from different parts of the world for a common agenda, I would like to discuss here how the notion of space and territory has changed, and how they can impact the way we organize. For getting organized, we must.

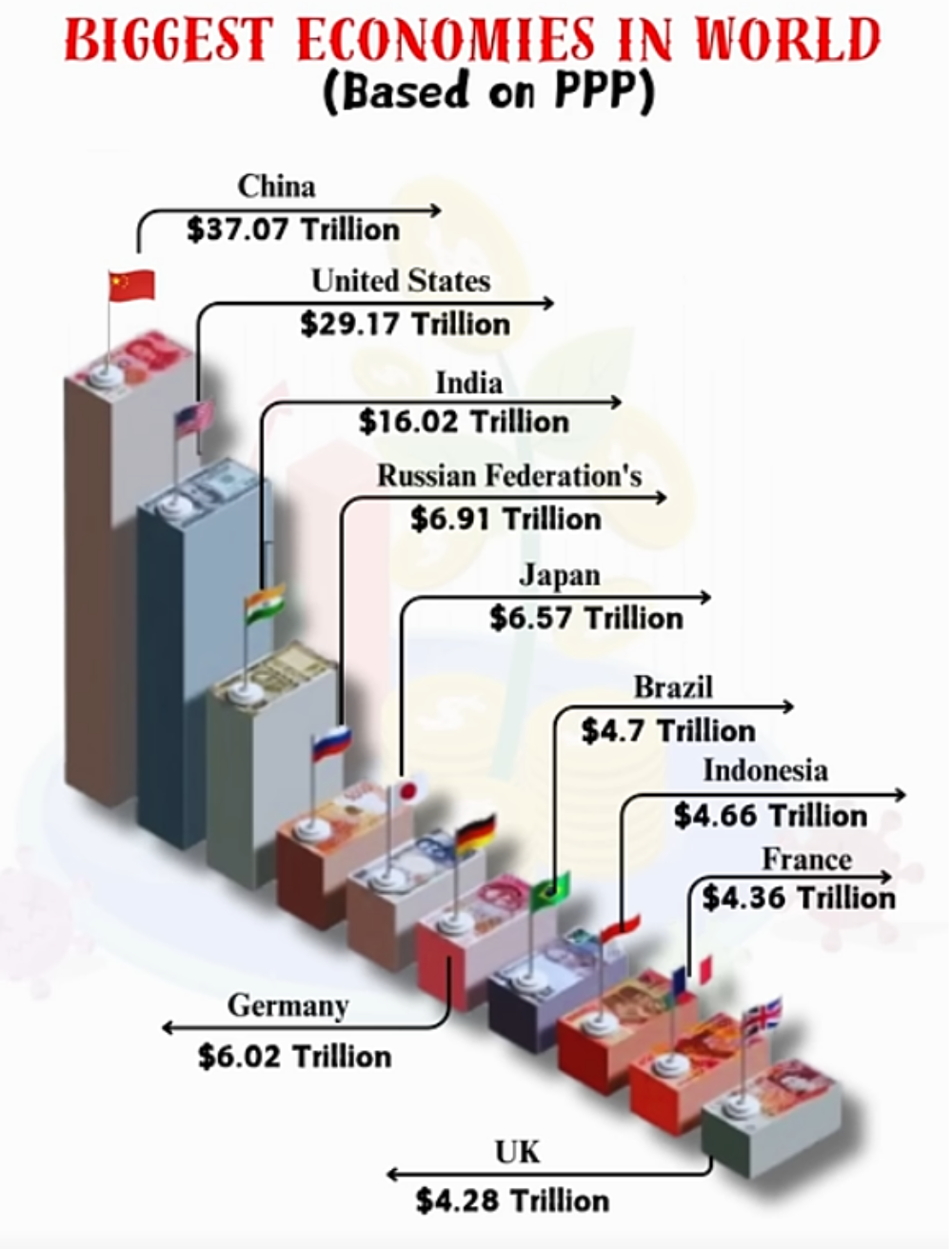

We could start with the fact that we cannot rely anymore on the hugely dominant power of the United States as a military, political, and economic key reference. In current dollar value, it still is the dominant economy, but in effective purchasing power parity, things look different. China has not only come ahead, but is moving on at a quicker pace. And its production capacity is based much more on useful goods and services, while the US industry represents only 8% of GDP, with military investment, financial services, information control, and other immaterial activities playing huge parts. Health services alone represent almost 20% of GDP, double the costs of other developed countries, a tribute to inefficiency rather than a higher economic contribution. China has built 40 thousand kilometers of high-speed railways, integrating the territory, and working with neighboring countries, while the US is building its first 700 kilometers in California and closing its borders.

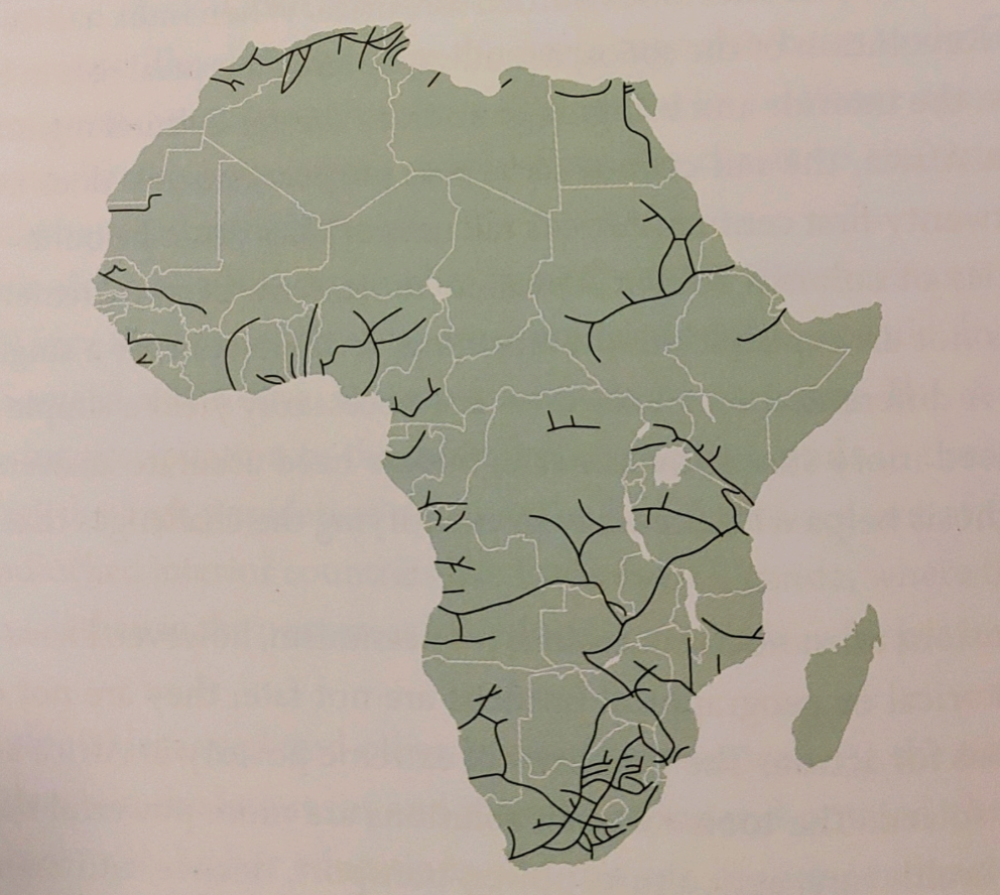

Railways are structurally important, as they integrate the territories, stimulate complementarity of different regions, and deeply change the costs of production. But they also change politics. The map below shows the railway system inherited from colonial times in Africa: it was not designed to integrate, but to drain, linking mining regions, forestry exploitation, export-oriented agriculture, with ports, and with the colonial interests. A country can become independent (Namibia only in the 1990s), but the infrastructure was designed for economic dependency, and so it remains. Weaving the African territories in a common economic space by means of an integrating network of transportation infrastructure would allow for the reorientation of its production capacities to its own needs.

Internal trade flows are directly hit. East Asia's internal trade flows in 2020 reached $5.4 trillion, while they represented only $100 billion in Africa. Such a fragmented continent is easily picked by previous colonial powers and the more recent corporate networks. These primary exports serve in turn to pay interest on the foreign debt, instead of funding internal investment in production, infrastructure, and social policies.

Source: Jeffrey Sachs, The Age of Sustainable Development, 2015, p. 138, Africa’s Railroads.

Source: Jeffrey Sachs, The Age of Sustainable Development, 2015, p. 138, Africa’s Railroads.

A report by Matthew Martin and David Waddock on developing countries shows the dimension of the drama: “A new Debt Service Watch database prepared for this report shows that when measured by the burden of debt service on budgets, this is the worst global debt crisis ever. In 2024, debt service is absorbing 41.5% of budget revenues, 41.6% of spending, and 8.4% of GDP on average across 144 developing countries: figures much higher than those before relief was provided to Latin America in the 1980s, and to HIPCs from 1996. Most importantly, service exceeds all social spending, and is 2.7 times education spending, 4.2 times health, 11 times social protection, and 54 times climate adaptation1.” Brazil suffers from similar deformations, the transportation system drains primary commodities to ports, and we still have to build an effective transcontinental railway connection. It is a key issue, for the world economic center is clearly moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And it will connect Latin American countries.

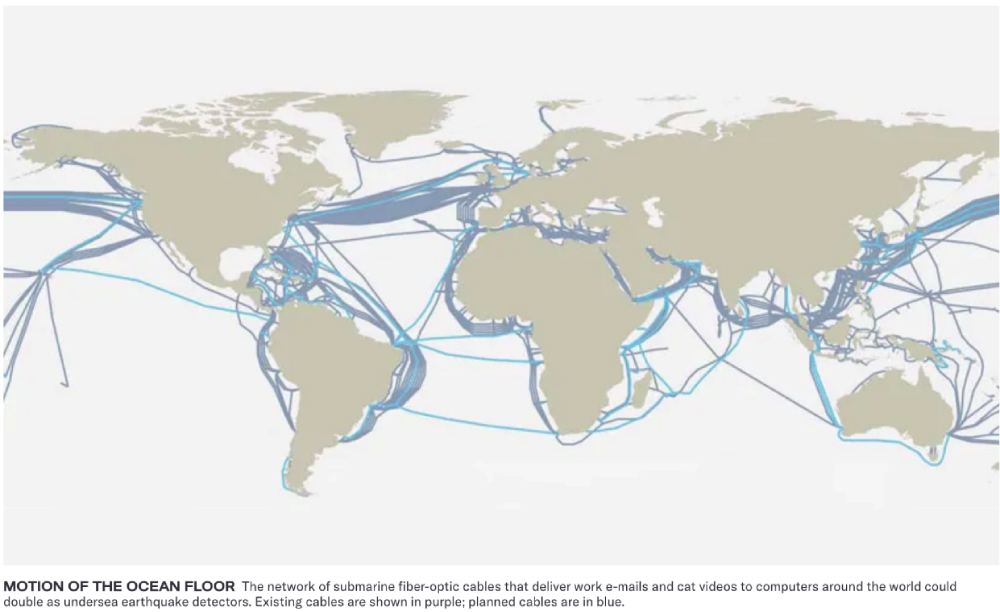

The communication infrastructure presents similar deformations, with major capacities held by the Global North, and in particular the United States, with the power of the communication platforms.

The UNCTAD 2021 Digital Economy Report shows how concentrated this control has become. “The largest such platforms – Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet (Google), Facebook, Tencent and Alibaba – are increasingly investing in all parts of the global data value chain: data collection through the user-facing platform services; data transmissions through submarine cables and satellites; data storage (data centers); and data analysis, processing and use, for instance through AI. These companies have a competitive data advantage resulting from their platform component, but they are no longer just digital platforms. They have become global digital corporations with planetary reach; huge financial, market, and technology power; and control over large swathes of data about their users2.”

Instead of integrating global space and territories, the system tends to serve the global drain. According to the Report, “with data and cross-border data flows growing more prominent in the world economy, the need for global governance is becoming more urgent”, and we must ”recognize that current global institutions were built for a different world, that the new digital world is dominated by intangibles, and that new governance structures are needed.” In the present structure, we face ”competing vested interests associated with the capture of rents from the use of digital technologies and data” (p.18).

The global financial behemoths and the information and communication platforms all belong to the immaterial economy, so well studied in L’immatériel by André Gorz. Computers, algorithms, clouds, AI, and the radical transformation of what we call nations, or territories. Paul Krugman sums it up: “It is not just that global trade now makes up a larger share of economic activity than in the past; it is also that the complexity of international transactions is far greater than ever before. And the fact that so many of these transactions pass through banks and cables that the United States controls gives Washington powers that no government in history has possessed3.”

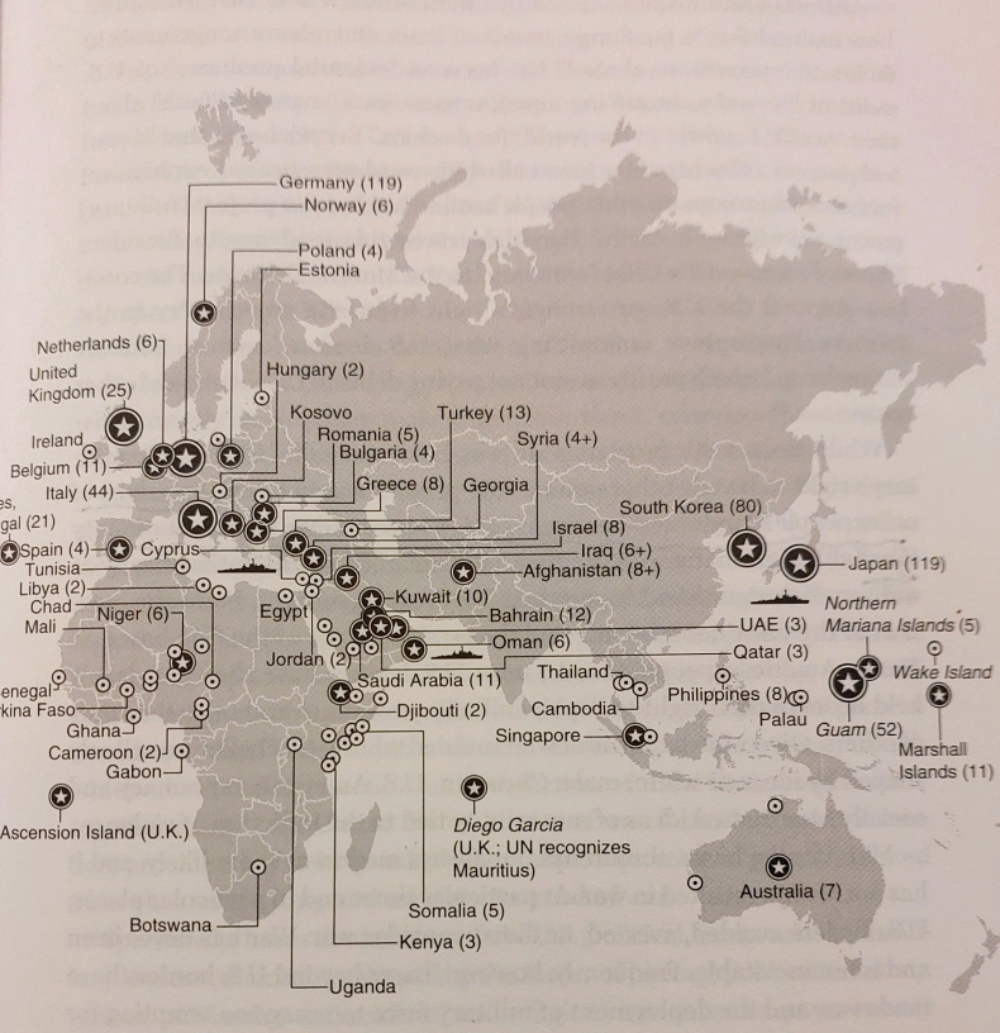

US Military bases abroad, 2020 (Americas not included here).

War-mongering is also building a different global territorial map. A sweeping image of the global US power network can be seen on this US network of military bases map. The numbers attached to the country names indicate how many bases the US has in each country. “As of 2020, the United States controlled around eight hundred bases outside the fifty U.S. states and Washington, DC. The number of bases and the secrecy and lack of transparency of the base network make any graphic depiction challenging. This map reflects the relative number and positioning of bases given the best available data4.” This map is a global view; David Vine’s study presents an impressive level of detail.

The corporations and the military bases do not constitute independent power structures. If we take the major western arms manufacturers, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon Technologies, Boeing, General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, L3Harris Technologies, Leidos, they are all American, while BAE Systems belongs to the UK, Leonardo to Italy, and Thales Group to France, but all of them are heavily controlled by the dominantly American major asset management platforms: Vanguard, State Street, BlackRock, Fidelity Investments, UBS, Morgan Stanley, Allianz/PIMCO, JPMorgan Chase, Amundi. Peter Phillips, who presents these details in his The Titans of Capital, brings this touching commentary: “The world would be a decidedly better place if the hundreds of billions now invested in socially harmful products and activities were allocated for human betterment5.”

Overall, it is interesting to watch how the different areas of globalization are moving, with different rhythms and clashes or complementarities according to the dominant global corporate interests. A chaotic mix of colonial past and top speed integration, of giant fortunes and hunger, of populations deprived of clean water while billionaires are planning for Mars. I picked information on the 5.6 million children dying of hunger every year on an AI software, top modernity showing present-day tragedies. In Bamako, Mali, stuck in traffic on a major avenue, I stared at a tiny shop displaying a shining sound kit, loudly transmitting the Epic of Sundiata, a 13th-century prince. The man in the shop is concentrated on his cellphone. Mali is also stuck in modernity. We are facing this strange mixture of space and time running at different speeds, rules of the game belonging to a different century, the institutional framework breaking down.

Back to San Sebastián and the meeting of so many countries and institutions, building ASETT, a social economy think tank, centered on social and solidary economy initiatives. At the meeting, the SEWA cooperative federation in India, to give an example, showed how it brought together millions of women who built their credit collaborative system, restructuring society from the bottom up. This kind of economy represents, as an order of magnitude, 10% of GDP in different countries, and do not have global visibility, as they are dispersed throughout the world. But they are giving an impressive example of radically superior efficiency in responding to the needs of the populations, not just profit-maximizing at the top. It certainly is much weaker than the global corporate system, but the same technologies that have built the overall financial drain and attention industry manipulation can be used to build the local social economy initiatives into a powerful collaborative network.

Notes

1 Matthew Martin and David Waddock, Resolving the worst ever global debt crisis - Debt Relief International.

2 Digital Economy Report, UNCTAD.

3 The American Way of Economic War at Foreign Affairs.

4 United States of war: a global history of America’s endless conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State by David Vine, 2020, University of California Press, p.5.

5 The Titans of Capital by Peter Phillips – op. cit. p. 161- “The two largest publicly traded private prison companies, which both have a history of human rights violations and documented inmate deaths, receive more than $1.42 billion in investment from the Titans.” So long as it makes money…