For decades, the European dream was clear: work, save a little, and someday buy your own home. From Portugal to Germany, from Italy to Poland, owning a house or a small plot of land was once considered attainable, even for factory workers or farmers with modest incomes.

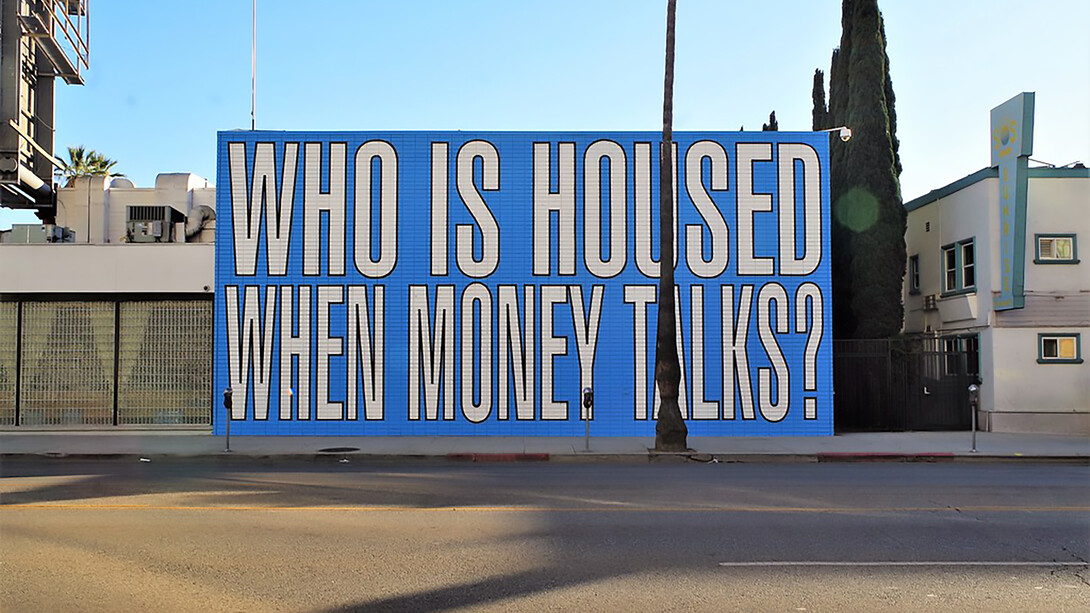

Today, that right has vanished for millions. A growing number of Europeans, especially the young and working-class, find themselves locked out of the housing market. The housing crisis is not a temporary glitch but a structural consequence of neoliberal market dynamics, specifically the transformation of housing into speculative financial instruments for elites.

When our homes became their assets

Let’s start with the basics. In the past, even the working-class people with no inheritance or prestige—really anybody—could build or buy their own home. Now, even middle-class professionals with degrees and stable jobs struggle to rent a flat, let alone buy a home.

So… What changed?

Homes stopped being primarily places to live. They became vehicles for investment, speculation, and wealth storage. Property is now a commodity to be bought, flipped, rented on Airbnb, or held empty until prices rise.

This shift, which is part of a broader trend known as housing financialization, is disfiguring the urban landscape and eroding the social function of cities as inclusive, livable spaces.

How does it work?

The current model is simple but brutal. Wealthy individuals and investment funds buy up properties, especially in attractive urban areas. They either convert them to short-term rentals (tourism) or luxury developments or simply sit on them while values climb. Meanwhile, ordinary people are priced out, rents skyrocket, and entire neighbourhoods become empty playgrounds for the global elite.

Essentially, housing has been colonized by capital, absorbed into a transnational logic of capital accumulation, often at odds with the right to shelter and urban belonging. And as with any colonization, the locals - workers, students, migrants, families, the common European - are displaced.

Who’s winning?

International investors, who see property as a safe, appreciating asset;

Real estate funds, which buy dozens or hundreds of units at once;

Short-term rental platforms, which allow landlords to make more in a weekend than they would in a month of long-term leasing;

Wealthy individuals are using programs like Golden Visas to acquire residence permits in exchange for luxury real estate purchases.

These players are not competing with local families; they represent a structurally advantaged class that actively displaces local residents through capital-backed exclusion.

Who’s losing?

Everyone else. Especially young Europeans, who can’t afford to move out or are forced to rent indefinitely, working-class families, who spend half their income or more on rent; migrants, often crammed into substandard housing or exploited by predatory landlords, small towns and city centers, which lose population and identity as homes are hoarded or turned into tourist apartments.

A growing segment of the European population is aging without assets, property, or economic security—a reversal of post-war social mobility that signals a breakdown in the social contract.

Why this matters

This crisis isn’t just about housing; it’s about the fabric of European society.

When people can’t access stable housing, they delay or abandon plans to start families. Public trust in democratic institutions erodes, leaving populations more susceptible to authoritarian or populist rhetoric—often funded or supported by the very financial interests exacerbating the crisis—and they experience increased mental health issues.

A society where a majority cannot afford a place to live is a society where democracy, cohesion, and stability are under siege.

The convenient scapegoat

Across Europe, political actors are shifting blame to poor migrants, painting them as the cause of housing shortages. Yes, overcrowded flats exist. Yes, migrants sometimes share small apartments in difficult conditions. But let’s be clear: these migrants aren’t buying properties or outbidding locals. They’re victims of the same broken housing system as other Europeans, not the cause of it. Such scapegoating deflects scrutiny from systemic issues: growing inequality, speculative capital flows, deregulated property markets, and decades of underinvestment in public and social housing.

It’s not the migrants hoarding apartments; it’s the investors.

Golden visas: the foreigners they usually welcome

Take Portugal, for example. For years, it offered Golden Visas, which is a scheme where rich non-EU citizens could gain residency by buying property worth half a million euros or more, often in cities already suffering from housing strain.

These buyers didn’t need to live in the country, often leaving the homes empty and contributing to price inflation and gentrification.

The scheme was finally restricted in 2023, but its effects remained and similar programs exist across Europe. It’s a system that opens the door for the rich while locking out the local population. And guess what the response of the Portugal government to this housing crisis was. Bring the Golden Visas back!—prioritizing foreign capital over domestic social cohesion, once again.

Barcelona: a glimpse of resistance

Not all hope is lost. In Spain, Barcelona has become a symbol of resistance against housing injustice. The city has cracked down on Airbnb licenses, imposing quotas for affordable housing in new developments and supporting tenant unions and cooperative housing models.

Movements like Sindicat de Llogateres are mobilizing citizens to fight rent hikes, evictions, and speculation. The message is spreading: Housing is not just a commodity, it’s a right we’re watching being slipped through our fingers because we thought feudalism was gone ages ago.

What happens if we do nothing?

If unaddressed, current trends will transform Europe into a continent where urban life and property ownership are privileges reserved exclusively for the wealthy, social mobility will collapse, intergenerational inequality will only deepen, and democratic legitimacy will erode, because it’s no longer serving the people. Though the housing crisis is not inevitable, the entrenchment of right-wing populist agendas, which often oppose regulatory interventions, makes it increasingly probable.

It is the result of political choices, economic models, and power imbalances. Governments retain the tools to counter this trajectory: enforce housing market regulations, impose taxes on speculative real estate, reinvest in public housing, and guarantee robust tenant protections. The question is, do we have the courage to treat housing as a right, not a privilege? Because once people lose the ground beneath their feet, they lose everything. And when enough people are pushed out of the system, the system itself begins to collapse.

But concrete policy tools do exist. When a significant portion of the population is excluded from stable, affordable housing, the consequences are not abstract. They manifest in social fragmentation, economic stagnation, and declining trust in institutions. Over time, this erodes the foundations of democratic and overall economic stability.

Tackling the housing crisis is not merely a moral imperative; it is essential to safeguarding the democratic fabric and long-term socio-economic resilience of Europe.