Being African in today’s world sometimes feels surreal—as if we’re split between two realities. On one hand, there’s the rooted African, grounded in their communal traditions and fixed in the cultural values that they carry daily, and on the other hand, there is the modern world, built on systems that don’t serve us, systems that for a long time were designed to work against us. Because of this, there is a deep psychological disconnect that usually plays out in our societies, a disconnect that often seems absurd and reveals the dissociation of these institutions we serve so faithfully.

Over the course of the last century, African nations have fought with trial and error to consolidate their traditional and cultural values with Western systems. Somehow African governments never seem to operate as efficiently or as swiftly as their Western counterparts, and although we place blame on corruption and rightfully so, there is a deeper cause behind it. The corruption observed today stems from greed, an impoverishment of freedom, a lack of opportunity and resources denied to Black people for so long that by the time most countries gained independence, the nourishment of having disposable opportunities created overindulgence in many politicians; they just can’t have enough after having so little for so long.

But let’s shift the focus from always blaming corruption or even colonialism to assessing our systems. While it’s important to acknowledge the damage done by those two factors because of how intertwined they are in our social lives, they are not absolutes. Western institutions weren’t designed with African people in mind, so it’s not surprising that these frameworks don’t reflect who we are. It's this mismatch that creates dissociation—a detachment of courts to social coherence, parliaments to cultural identity, and education systems to national purpose.

In a globalized world where the "first world" countries lead us in nearly all social categories, we are always playing catch-up, always on the back foot, always receiving the short end of the stick. Our groundbreaking cultural innovations are distorted by the inability of our societies to provide the necessary tools, systems, and structures that fully enhance African development.

What is dissociation?

In psychology, “dissociation is a break in how your mind handles information. You may feel disconnected from your thoughts, feelings, memories, and surroundings. It can affect your sense of identity and your perception of time.” In the African context this dissociation is spiritual and not the religious kind; our dissociation stems from a break in the essence of being.

Our essence is blinded by foreign values; these values manifest in the real world as social, cultural, and systematic disorientation. As a result, many Africans find themselves in systems that feel alien. We follow global laws and policies that were never designed to support our growth. The absurd reality of this dissociation is that we don’t even fully believe in these institutions; we serve them purely because of convenience. We cannot rid ourselves of this bondage because there is nothing behind these structural systems to fall back on.

One of the reasons we remain trapped in this cyclical loop is that we still have yet to answer the question of who we are! From the micro to the macro, as communities, individual countries, and more importantly as a continent, what does it mean to be African? How do we create systems that reflect our identity and reality?

What is Negritude?

Great leaders from the continent and the diaspora have long been concerned with the idea of a cultural movement with political aspects being indirect and secondary. Negritude, started by figures such as Leopold Senghor and Aime Cesaire, “sought to reclaim Black identity and cultural pride. It was devoted to defining and expressing the special, distinctive, cultural characteristics of Black people and then to asserting the worth of those distinctive characteristics.”

The movement was focused on defining the cultural identity of Africans through the synthesis of Western systems. According to Senghor, some of its most important characteristics included centering the creative potential of Black Consciousness, promoting the appreciation of Black history and culture, and reclaiming the value of Black culture, which had been tainted with primitive impartation.

The synthesis of Western systems with African cultural identity is very important in that the solution starts with us rediscovering our cultural identity in its entirety. This rediscovery is not simply for nostalgia; it’s about building future systems that are more attuned with African values and morals. By anchoring our identity, we can sift out specific aspects of Western systems that have long hampered our progress.

If Blackness shrinks or feels limited under the crushing, often insidiously damaging weight of western systems of oppression, specifically the endemic tolls of structural racism, then the extraordinary provides space to construct new realities and absurdist visions that reconfigure what Blackness as an aesthetic can be.

To move forward we must harness our most powerful tool: creativity.

Afro-surrealism

That creativity can be found in the confines of Afro-surrealism, an artistic and literary movement that depicts the Black experience through the lens of the absurd and unlikely:

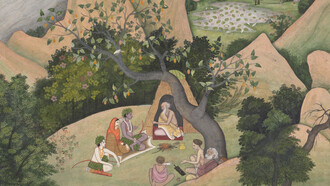

The world of Afro-surrealism is a world trying to manifest our future, the metaphysical and spiritual essence guided by the ancestors who are eager to give Africans the psychological motifs that will enhance African consciousness towards a Renaissance.

It’s quite crucial to note the importance our psychological retinue plays in the revival of past motifs; the cleansing of Western ideals, which have affected our worldview, is fundamental in working as a therapeutic experience eager to burst out as a creative force.

However, we should always acknowledge the contributions of Western culture to our societies and not throw it away for it has become a part of our identity too.

By engaging with our past, we’ll develop a more astute awareness of the present, thus enhancing our nectar for the future development of African culture.

Uncovering an invisible world: Afro-surrealists believe that there is an invisible world that's striving to manifest, and it's their job to uncover it.

Restoring the cult of the past: Afro-surrealists restore the cult of the past.

Using excess as a means of subversion: Afro-surrealists use excess as a legitimate means of subversion.

Establishing new narratives: Afro-surrealists develop new narratives and origin stories to correct the lack of representation.

Striving for rococo: Afro-surrealists strive for the beautiful, the sensuous, and the whimsical.

The invisible world that seems to manifest in those who lean towards the art of creation is a summation of the surreal absurdity of our reality mingling with the psychological pantheons of our ancestors, their echoes ringing evermore in our lives, forcing us to confront our past and their past with a new, clear lens. To break free from dissociation, we must experience a cultural renaissance, a rebirth of values, thought systems, and creative energies that will reconstruct the African spiritual essence.