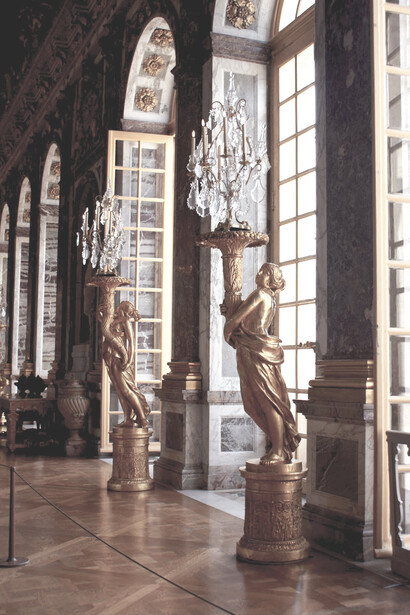

Often overlooked is France’s Louis XIV. The Sun King’s long reign (1643–1715) rarely gets the spotlight in modern foreign policy analyses. The ever-shiny Napoleonic adventure a century later absorbed all the light away from Louis’s wars. The Emperor has a gallery of legendary victories and world-shaking defeats to equally boast and lament; Louis has neither. The Corsican climbed from obscurity to the highest elevation, and his fall is the stuff of movies. Louis was at the top by birthright and remained there till death.

Yet, a twist sets Louis apart from Napoleon and every other aspiring hegemon in modern history, such as Wilhelm II, Hitler, or Hirohito. He passed peacefully in his bed with his kingdom, France, still in one piece and still a great power. Louis even left the country larger than he found it, something Napoleon or others cannot brag about. Louis’s fluctuat nec mergitur skirts the edge of boredom.

That is precisely why this ending alone warrants our attention.

I began researching Louis XIV almost accidentally a few years ago. But the more I investigated, the more convinced I became that the Ludovician era held some lessons for our own. Like Napoleon, Wilhelm II, Hitler, or the Cold War Soviet Union, Louis XIV sought continental hegemony. Nonetheless, unlike them, Louis emerged relatively unscathed. His secret? A remarkably forward-thinking approach to ending large wars.

Peace from a position of strength

In How Louis XIV Survived His Hegemonic Bid (Anthem Press, 2025), I argue that the Sun King’s survival was the fruit of his strategic moderation. Louis made significant wartime concessions, not out of desperation, but from a position of relative strength. He was willing to end wars before his enemies became irrevocably unified, undermining countervailing coalitions by offering just enough to peel off partners or soften opposition.

Other aspiring hegemons, the most typical perhaps being Hitler, tend to dig in, clinging to maximalist aims until the world aligns against them irreversibly. Louis chose differently. He recognized the value of calculated retreat. His mantra was straightforward: break the enemy coalitions before they break you. This coalition-breaking strategy, made possible by the man’s deep understanding of international politics, enabled him to survive.

Such behavior stands in stark contrast with more recent hegemonic bids. From Habsburg Spain to Imperial Germany, would-be hegemons often sacrifice moderation on the altar of hubris. The result has always led to disaster. Louis, by contrast, preserved his country and his military while still expanding its borders. His wars were massive, but none proved fatal.

Louis’s moderation is clearest across the major wars he fought: the Dutch War (1672–1678), the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1713). In each case, his forces were formidable, but his war aims were ultimately negotiable. At the end of each war, Louis returned large gains and conquests in exchange for acceptable peace terms. These decisions reflect a leader who accepted exiting with only partial victories and draws.

Why Louis matters now

The argument has implications far beyond the world of wigs and court intrigues. International relations, as a field, has long focused on the great power wars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, treating everything prior to the Victorian era as antiquated and unworthy of research hours. That is a mistake.

Louis XIV’s case questions international relations’ foundational assumptions about hegemonic wars and war termination. Can great powers exit major conflicts without annihilation? Can moderation achieve strategic goals? The answer, Louis suggests, is yes. While twentieth-century great power wars saw industrial slaughter and total war to the finish, Ludovician France charted a subtler course.

International relations theory, especially realism, assumes that great powers will inevitably provoke balancing coalitions. But Louis anticipated this and preempted it. His actions reveal a sophisticated grasp of balance-of-power dynamics and coalition psychology. This is quite different from Hitler or Wilhelm II, for instance, who thought they could bulldoze their way to hegemony.

Hence, the Sun King still has light to shed.

The United States today confronts the rise of China and Russia as the latest contenders for regional hegemony in the Indo-Pacific and Europe, respectively. The burden of breaking coalitions now falls on Beijing and Moscow, much as it once did on Louis XIV. Surrounded by hostile alliances, today’s two revisionist great powers must navigate the same dilemma Louis faced. If a general war breaks out, how can adversarial unity be fractured to end the conflict on favorable terms? The Sun King’s answer offers a potential solution for Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. Indeed, the former possesses some traits and foreign policy behaviors that resemble those of the French king. For these modern hegemonic challengers, Louis’s legacy may not show how to win outright, but it at least gives an example of how to escape total defeat.