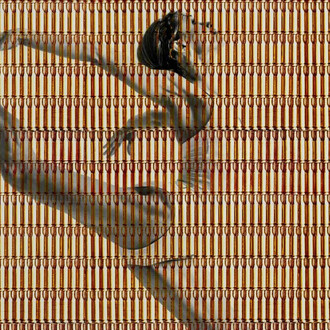

The complex grace of the lines of Petviashvili's graphics is shockingly alluring, domineeringly earnest, and gracefully gratifying. It is as if the sternest forms of a repressive past have been suddenly liberated by the serpentine air of soul-searching, transforming the starkest memories of the collective into a celebration of the individual.

In the oeuvre of Rusudan Petviashvili, one discerns not only the prodigious talent of a child virtuoso but the profound artistic trajectory of a woman who has transformed the graphic idioms of her Soviet childhood into a radiant dialect of personal mythology. Born in 1968 in Tbilisi, Georgia—at the cusp of Brezhnev’s stagnation and amidst the visual austerity of late-Soviet aesthetic policies—Petviashvili’s early recognition was as meteoric as it was improbable. Her first personal exhibition, held when she was merely six years old, heralded the emergence of an artistic consciousness not only precocious but disarmingly whole. The seamlessness of her line, drawn often in a single gesture, sings like some alien paen, an anthem in bridging the dark past and the promise of future.

By the age of thirteen, she had exhibited her works across France, culminating in a Parisian show that announced her as a legitimate cultural export from behind the Iron Curtain. In retrospect, what makes these early works particularly significant is not simply the precocity of their draftsmanship but their quiet subversion of the prevailing visual orthodoxies of the Soviet bloc. While Socialist Realism mandated a form of ideological legibility—heroic bodies, didactic clarity, the elevation of collective labor—Petviashvili’s drawings were already attuned to a different sensibility: ornamental, introspective, and mythopoeic.

Indeed, the graceful authority of Petviashvili’s lines functions as a kind of visual rebuke to the visual culture of repression. Her aesthetic can be read as a starkly poetic invective, adumbrating in lush forms and harmonious colors, where the last vestiges of social realism of her childhood lay to waste, making ample space for a cathedral of sensuality and femininity. If Socialist Realism sought to discipline the body into collective function, Petviashvili’s forms curl away from such constraints. Her lines do not march; they meander, unfurl, and breathe. In doing so, they offer a post-Soviet hymn to the individual, to beauty unshackled from didacticism, to eros as a mode of knowledge.

The historical positioning of Petviashvili’s work must also be understood in relation to Georgia’s unique cultural hybridity—a crossroads of Christian mysticism, Persian miniatures, and Byzantine grandeur. But in her personal reframing of these lineages, they fuse into a postmodern fluidity of identity impossible to classify, resisting temporal fixity. Her one-touch drawings, delicate yet commanding, move across time—anchored in classical technique yet fervently contemporary in their emotive potency. One might draw comparisons with the Viennese Secessionists, with Klimt’s ornamental eroticism or Schiele’s emotional contouring, yet her work remains unmistakably her own, rooted in a feminine cosmology that foregrounds intuition and inner life over formal rebellion.

Most tellingly, her palette—only emergent as a complex sensation out of the lushness of the lines—is neither garish nor subdued. It is ceremonial. Her use of color acts not as filler but as aura, enhancing the spiritual resonance of each image. Like a faint yet deliberate echo of Georgian folktales, or some spiritual Biblical narrative, Petviashvili demonstrates an unwavering belief in the capacity of the visual to do what the political never could: to transfix without coercion, to persuade through beauty.

Petviashvili’s inclusion in 2000 famous persons of the 20th century, as published by the Cambridge Biographical Centre, is emblematic not simply of her personal achievements, but of a broader recalibration of post-Soviet art history. This makes Rusudan Petviashvili’s a remarkable occurence that constitutes a deeply individualistic response to the condition of modernity as lived through the fissures of history and memory. After a tour of her oeuvre, one perceives it less representation than revelation—each a hyperfine undoing of repression, each a monument to the ungovernable power of the line.

(Text by Albert Tang)