Susan Inglett Gallery is pleased to present the Gallery’s first exhibition with Brendan Fernandes, Within Reach.

Contemporary dancers will engage and activate a series of sculptures created by Fernandes that are inspired by West African headrests. Designed to preserve and protect intricate hairstyles during sleep, the headrests also carry cultural and spiritual significance as they were believed to invoke vivid dreams and guard against nightmares. That connection to the spiritual and ethereal is communicated in the dancer’s movements.

Reaching back to his early involvement in the NYC club scene, Fernandes choreographs a series of movements riffing off the highly stylized house dance known as voguing. Dancers strike a series of angular poses, bodies lying horizontal across the sculpture while arms extend vertically towards the sky in an act of spiritual solidarity.

By responding to these African-inspired artifacts in the language of contemporary Western dance, the gallery becomes an activated space of multicultural hybridity and conversation. Born in Nairobi to parents of Kenyan and Indian descent, and later immigrating to Canada, the artist’s multifaceted identity influences his expansive practice. Through a language of interdisciplinary media, Fernandes composes a layered narrative that critiques and dismantles colonial contexts.

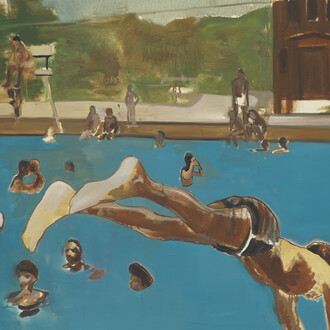

Within Reach further explores and animates the artist’s 2015 photographic project, also on view, As One. Created as a video commission for the Seattle Art Museum and later as a photographic series using the Cravens Collection at the UB Art Galleries, Fernandes choreographs the interaction of his dancers with the Museum’s collection of West African masks. The dancers act out a series of bows and curtsies traditionally known as a Révérence. Performed at the end of a class, a Révérence honors the efforts of both teacher and pianist.

Employing the language of ballet, a technique developed during the reign of Louis XIV to showcase courtly etiquette and status, Fernandes cultivates a moment of appreciation and an apology for the historically exoticized African artworks. In each image, the dancers act out gestures of respect and perhaps empathy for the masks that once played an important role in the rituals and performance of their own culture but are now isolated high on a plinth in the Museum.

By responding to these extracted African artifacts through European traditions, the artist references centuries of colonial deracination. Fernandes reminds us of how little we know or can hope to understand of these objects and their origin when viewed through the myopic lens of the West.