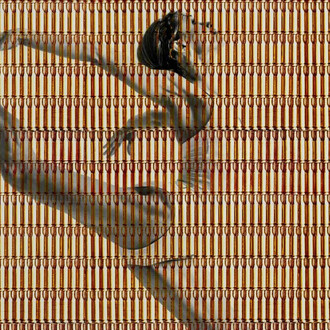

Changha Hwang’s paintings are some of the most interesting and strongest works I have seen as of recent. There is a strong graphical and pixelated element to them, with myriad rectangular, triangulated, chevron-shaped, sawtooth splayed upon one another, stacked in motley patterns. In Hwang’s older, mid-aughts imagery, the artist would often stack thin oblong and quadrilateral ladders that formed a latticework. In Hwang’s more recent paintings, there is an additive textural vim, galvanized by blanched aquamarine sprays that ripple into pocked small vapor, which, again, suggests digitality. The stacked geometrical elements now recall Mary Lum’s acrylic on paper and mixed media collages while the pixel-like squares that figure into fractured planes are reminiscent of Christopher Astley’s feigning post-internet raster images by way of pure painterliness. Hwang’s shapes are now filled out rather than left skeletal, licensing less optical climbing and transmission than layering. The latter, then, entails as much blocking-out, overshadowing, and negating information as it does additively positing it.

Art critic Pierre Sterckx has espied two related tendencies in Hwang’s paintings, which, he observed, seem “[t]o be born directly out of computer manipulation: same color grids: an infinite programmed superimposition of programmed luminescent flat tints”. Sterckx then relates this to the “technological environment” that subtends Hwang’s process. This second tendency, part and parcel of new media vernacular, is that digitality’s networked form. It is quite understandable that Hwang’s paintings, born from an awareness of digital nativity, tend towards the network as a mode of being—the very mode of being that philosophers of digitality like Bernard Steigler have argued becomes externalized, or, to borrow a term of art from mathematician Alfred J. Lotka, “exosomatized”. Where primitive human externalized his fist and teeth with tools like the hammer and knife, today we are networked creatures who do not consciously exact singular, token actions but are part of a reticulated mode of being. In turn, we tend towards externalizing that way of being in our vernacular—whether it be in the domain of speech acts (e.g., performing “initliasms” in everyday life, like the person who remarks “LOL”) or creative acts, as in Hwang’s networked works, which are not only networked in their constituent representational elements but in their broader mode of visibility (e.g., online gallery images, online reviews with digital images, etc).

But that there is a development from pellucidity and transparent oblongs to blocked-out fractured pieces also signals that Hwang’s paintings are attuned to a shift. This shift concerns the move from the California Ideology of optimism concerning a liberatory internet undergirded by promises of anonymity and free-flowing information sharing to that of digital oligarchy, meta-data collection, and the surveillance state. The surveillance state, rather than some encroaching presence, is bolstered by the contemporary internet user’s knowledge that they are being watched (thus self- surveilling, the panopticon internalized); but they are not knowledgeable of how this surveilling takes place, just as the black-box mechanisms of Big Data remain wittingly obscure. Hwang’s recent paintings, by remaining sensitive to digital vernacular but of a discretely cryptic kind—where eclipsed blocks and parallelograms plate and pleat the networks below—tracks this shift internal to digitality.

(Text by Ekin Erkan)