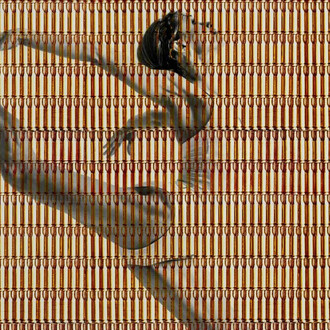

Ha Jaeyell’s background in visual design and advertising design seemingly informs his photography, albeit in a mode entirely distinct from Pop Art, and much more subtle. What visual design and advertising teaches the nascent practitioner is an attention to composition: that any work of art should be informed not only by its subject matter or stylization but, with equal vigor, the “cut-out” or framing of the subject. When a photographer undertakes their selection process and, for instance, chooses to take flora or fauna as their subject matter, they are presented with a framing question: what is to be left “offscreen”, so to speak, and thus relegated to the imaginary? What, then, is to be visually presented? Which trees should loom quietly, understood as excessive, and where should poetry blossom? This also brings to bear a much more subtle issue, which is that of editing. For, indeed, framing is a kind of editing. Traditionally, when we think of editing, whether executed with digital software (e.g., Brad Troemel, JODII, and other such net/post-internet artists) or in an analog sense (e.g., Kunie Sugiura), we think of an art-object, perhaps a photograph, that is manipulated after its subject has already been captured. However, the very choice of what will be captured and, consequently, what will not be captured, is also an editing choice—one which belongs to the aesthetic vision of the artist, and hence profoundly informs their artwork-to-come. And it is out of such editing/framing issues that Ha Jaeyell’s photography proffers ethereally-bedaubed profundity, casting magicscapes and adumbrated fantastical scenographies out of the natural world.

Remarking on his art practice, Ha notes that: "The world’s orthodox flow of photographic art places importance on the originality of the artist. All of [my] works are taken as-is with ‘storytelling’ incorporated into them, giving them this artistic vitality. The ability to capture a moment that can express the ‘story' of silence that nature tells at that instance, speaks to the artist's ability”.

These works often take utility poles, the winter sky, crinkled tree leaves, crescent moons, and barbed wire as their subjects. But, contra the Dusseldorf School of photography and myriad other photographers interested in the aesthetics of banality, Ha steeps these objects into wondrous, breathtaking compositions. Compressing the picture-plane, such that the background and central object are woven into a bustling, flat latticework, Ha’s photography does not lure us back into the natural world of the naked eye but prods us into revisiting. There is a moodiness—an elegant, shadow-scoped luminescence—that quietly shimmers in his muted works. In one particularly riveting photo, strands of Stygian tree branches braid and careen into one another like nettle-bitten spiderwebs sewn into a loose basket. A tangerine-tinged night sky blooms below—yet barely below, for recall the compression act; through the lower third of the photograph we see a series of fluorescent rectangles. Then we realize this is a skyscraper buried in the trees. Other works herald fewer indices anchored in the empirical world of recognizability. A hoary, silver-dusted photograph breathes ripples: it seems that these could belong to the sky or the sea. Only peering through the drab-dusted shadows can we make out reeds, soothing us into a river or lake. In yet another equally-nightlit photograph, we see naked, raspy tree stems spiraling and spraining against an invisible wind. A fleck of light dances above a dry branch—perhaps the moon twinkling her cheek or a star piercing the smog-sifted eve. If poetry were ever translated into photography, it is here that the act of version comes alive. Revealing and unveiling, these photographs are quiet, serene blanched stories ready for the pruning and plucking.

About the Critic

Ekin Erkan, PhD is a researcher in art history, where his primary areas of study are contemporary installation art, photography, and American & European modern art. He also works and writes in the philosophy of mind, philosophy of perception, and philosophy of art, wherein he takes up a historical vantage, keeping close at hand historical problems and textualism. He works as an art critic for several publications and as an art history researcher. He has been published in both academic and popular venues, with over 50 peer-reviewed articles, and has spoken at dozens of academic conferences.