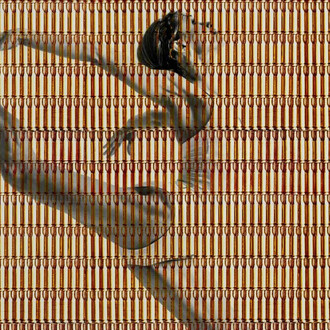

Like Alberto Murillo, Angels Grau has a background in interior design but, contra Murillo, takes a much more painterly approach to her depicted subjects. Nowhere is this clearer than her "Invisible Women" series, which features faceless portraits of feminine-coded figures. The faces are deracinated of any recognizable indices: there are no ears, eyes, teeth, lips, or other such anchors to tether us to the world of known or knowable faces. Instead, the series repeats several motifs: bobbed hair, a rectangular-cum-ovular facial shape, the outline of a neck, and the collarbone-crowned beginning of a shirt that, we must assume, continues off-canvas. The color schemes change in each portrait: sometimes the hair is a dark aquamarine, at other times a bronze-dashed copper-red, sometimes a verdant hazed green, or even a pasty warped white. The backgrounds also continually change, ranging from smoke-stricken flaxen gold to apricot-carrot or Stygian pooling black. At times, Grau’s portraits don gold or floral earrings—a brief window into their world of fashion and culture. A few such portraits also sport gargantuan hoop earrings and sizable afros (which come in light blue, purple, and brown), indicating that these are women of color. Some of the faces are more two-dimensional and painted evenly while other portraits allow for the brush strokes to make themselves more apparent, the uneven gesture spurring our gaze.

The act of mechanical repetition finds Grau taking on an almost automatized art practice while simultaneously imbuing it with the subjectivity that solely the human hand can only proffer. That is, these works simply could not have been made without the haptic touch of the artist's brush—these strokes are far from the crisp, almost digitally outlined images that Murillo gives us. Indeed, it is the textural, crumbling surface and not the smooth-sloped plane which dominates these works.

How ought we interpret these portraits? The artist statement tells us that, “[a]fter visiting Manolo Valdés’ studio, I felt the need to paint women like me. We are here and we exist. We are those Meninas. We are those women.” Grau is here speaking to works like Valdés Menina azul (2019), a sculptural appropriation of the Spanish Baroque master, Velázquez's, own Meninas (i.e., girls who served in royal court). The anonymity that Grau thus works with is one that not only gazes upon the sea of contemporaneous feminized faces but the history of eluded women’s’ bodies. But rather than paint the anonymous subjects past and present with full figurative complexity, Grau has chosen to repeat this historical anonymity by making anonymity literal, stripping all that would have made them recognizable. Such is a confrontational act where that which is being confronted is the allocentric worldview that has spurned the annals of patriarchal history.

There is, furthermore, a very marked sense in which Valdés formally informs Grau's own art practice. Valdés' paintings use the paintbrush to make apparent luminosity and lighting while weaving in symbology and collage, often with political messages undergirding these works. We see such political underpinnings in Grau’s own paintings. There is also a shared interest in femininity. Paintings like Valdés Azules (2021) and Retrato (2018) take the feminized portrait as a central locus; however, Valdés, wielding a penchant for analytic Cubist-crazed faces, retained the aforementioned humanist indices: not only do eyes, eyebrows, and lips transpire in Valdés’ paintings, but they are often doubled and re-doubled, such that we find boldly outlined faces that seem to have been warped and flattened from various angles. Grau, on the other hand, gives us an inescapable anonymity. Yet, despite the adversarial nature of Grau’s portraits, this is not anonymity as such. Vis-à-vis embellishments like hairstyle and jewelry, we can often ascertain the race of Grau’s subject(s).

Hence, these female-bodied figures could not be just anyone, but instead can be identified as part of a rather sizable populous that has been historically oppressed. The universality here professed is not a romanticized image of “color-/race-blind” viewership but that which dialectically presents the historical subject as both subjectively bound but anonymously treated. In turn, Grau gives us a genuinely political art practice.

(Angels Grau and Feminized Anonymity, Text By Ekin Erkan)