The title of this year’s regional exhibition, A Tooth for an Eye, is borrowed from a song title that reimagines the Old Testament code of corporeal retaliation (“an eye for an eye” or “a tooth for a tooth”), proposing noncommensurable exchange in its stead. Simultaneously, the title points to the human body as a central aspect of social and political systems across history. Bodies are much more than their appearances: they are biological battlegrounds, projection surfaces for fantasies, sites of individuality, scenes of confrontation. Since the beginning of humankind, they have been used, instrumentalized, manipulated, fragmented, transformed, and commercialized in innumerable ways.

Above all, bodies are transient vessels; only traces of their existence remain after death. Despite this vulnerability, they are our ur-architecture. Their permeability defines how and what we sensually experience, and they are powerful tools for shaping the world. All sixteen artists in this group show—featuring artists from the region—understand this. They reference the body while detaching it, abstracting it, extending it, and transforming it in order to grasp its manifold biopolitical dimensions, all the better to re-form and rethink it.

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor’s body already forms part of Gerome Gadient’s sound piece, which records the footsteps of visitors, subjects them to logarithmic manipulation, and transmits them back into the exhibition space as an eerie soundtrack. Other works nearby likewise evoke the body through its traces and the environments in which it circulates. Daniel Kurth’s Self Portrait shows the artist’s own worn-out sneakers, from which a fugitive smoke rises, as if the artist himself has evaporated. Kurth also uses the absent body in another piece, Amazing Luxury Hilltop Houses That Will Blow Your Mind, a compilation of commercials for luxury homes that removes all human life, show- ing only the empty, pretty shells of a commer- cialized, glossy world for people with capital. In the center of the room, Jeronim Horvat’s Mono- bloc, a plaster cast in two parts taken from the most widely available plastic chair in the world, speaks about both the globalization of modern consumer culture and the bodies that are shaped by its products. The photographs by Claudio Rasano enact a similar excision of the human. In this selection of stark, carefully composed color images from the series Everyone lives in the same place like before, the photographer documents buildings and con- structions in which humans are palpably absent.

In room 2, a work by Philipp Hänger, Es gibt NUDE – und es gibt NAKED (There is NUDE— and there is NAKED), unfolds on two walls and will be continuously altered over the course of the exhibition. Hänger works with layers of photographs (both found and newly made), textual elements, and overpainting, to create a visual essay that fuses object and subject, (cor- poreal) protection and exposure, blankness and image excess. The piece is joined by two se- ries of small-scale sculptures by Jeronim Horvat in bronze and high-tech plastic, derived from the modern fitness and entertainment industry. While they once served as extensions of the hands of adolescent gaming aficionados or acted as bicycle bottle holders, they now look like strange prosthetics from some future world.

Other consumer objects have inspired the artists featured in room 3, including Axel Gouala, who combines exotic-looking plastic plants with various devices that are supposed to make modern life easier and more comfortable, or make bodies fitter. These hybrid forms gain playful new life while foregoing the bodies they were originally meant to serve. Camille Brès’s figurative paintings also address the possessions, environments, and decor that surrounds people—portraying human life only through indirect representation.

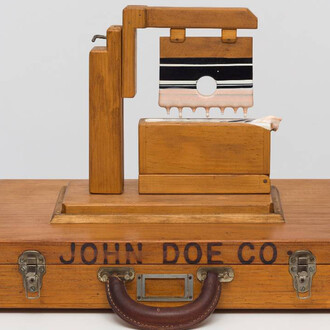

Everyday objects of another kind are the basis for the series Armes Blanches (melee weapons) by Inès P. Kubler, who has encased various sharp implements (scalpels, oyster shuckers and others) in wax to resemble prehistoric artifacts, like humankind’s first tools. In a nearby showcase, Kasper Ludwig’s faces and heads made from balloon casts are laid out like anthropological specimens. Simone Steinegger also fragments the human body, staging a clinical spare-parts depot in the exhibition. The surreal- istic features of Mona Broschár's painterly still lifes suggest ambiguous associations between colorful comestibles and bodily interiors, while also giving certain foods an animistic life of their own.

The final room of the exhibition hosts Hannah Gahlert’s sculptural installations, in which a variety of materials meet: soft and hard, arching and writhing, sometimes tamed only by a metal box or ceramic bands. The objects of Dominik His, on the other hand, appear more controlled in their materiality, their shelllike surfaces and meticulously crafted forms evoking alien eggs or imaginary architectures; they are also studies that, like Gahlert’s works, speak through and about an implicit, if foreign, corporeality. Simona Deflorin’s works on paper are expressive, wild syntheses of goddess, human, and animal, full of dynamism and dark power. An amorphous object lies in the back of the space: a mattress emptied of some of its material insides and filled with the worldly possessions of Dorian Sari, its maker.

By inserting his property into the “skin” of an object marked by traces of the artist’s own life, he reminds us that a bed not only serves bodies as a resting place, but is traditionally linked to birth, life, and death. The painterly figures in the triptych by Mirjam Walter propel their interiors almost violently outward, suggesting bodies in which neat distinctions between interior and exterior, self and other, exuberance and containment, are volatile and unreliable.

Conceptually, experimentally, sensually, expres- sionistically, these works dissolve the body in smoke, follow its traces, isolate it, break it into parts, show the limits of its controllability, and cast a sharp eye on its environment and its positioning within it. And like a body, the exhibition itself is not a consistent entity, but morphs from space to space. It brings together different strategies of artistically dealing with corporeal representation and the relation between humans and objects. Whereas the first rooms contain works that use documentary and mimetic techniques, the spaces that follow take analytical, structural, or quasi-archaeological approaches. In the last room are the most abstract and organic forms of all. The exhibition itself thus undergoes a kind of transformation as visitors progress through it, from concrete, figurative, but also conceptual representations to more expressive forms, at once sensual, subjective, and visceral.