It is a national pride in Argentina that university education is public and tuition-free. It represents the convergence of two major political traditions in the country. On one hand, the 1918 University Reform, associated with the Radical Party, democratized universities in the early 20th century. On the other hand, Peronism made university education free in 1949. Regardless of social class or previous schooling, all Argentine citizens and residents can pursue high-quality, tuition-free undergraduate studies in any of the more than 60 public universities across the country.

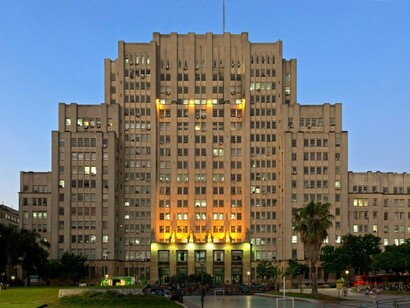

This article does not aim to recount the history of Argentine universities, but to focus on their current situation—and especially that of the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), the most prestigious and largest university in the country, with over 330,000 students. Since Milei was elected, it was foreseeable that public universities would be affected by his “chainsaw” austerity agenda. It is not the first time we have experienced—myself included as a UBA professor—budgetary asphyxiation. The 1990s under President Menem were not much better than the present: there was barely enough money to pay salaries and essential services.

In December 2023, the government announced that it would send a bill to Congress to allow charging tuition to non-resident foreigners in public hospitals and universities. The proposal failed and never materialized into policy. At least in the university sector, the announcement was merely a headline designed to appeal to xenophobic sentiment. The number of foreign students without residency is negligible; anyone who comes to study in Argentina obtains residency quickly, as degree programs typically last about five years. Moreover, foreign students are generally migrants, not people who come solely for education.

On April 23, 2024, the Federal University March took place—the largest protest against Milei's administration to date and one of the biggest mass mobilizations since the return of democracy in 1983. Citizens across all provinces took to the streets to defend public education because, as mentioned, Argentina’s public university system remains a high-quality institution and a pathway for social mobility for millions. The testimonies are endless: children of domestic workers and factory laborers who became professionals thanks to public universities.

This brings us to December 2025, two years into the administration of La Libertad Avanza. Public sector salaries have been frozen since 2024, and research funding has been restricted. This is an indirect mechanism of cuts: there are no dismissals, but wage stagnation in an inflationary context with a rising cost of living forces university faculty and staff to seek other employment. For example, an assistant professor with a simple dedication (10 hours per week) earns roughly USD 150 per month, and a lower-tier administrative employee earns around USD 700. In Buenos Aires, a subway ride costs USD 1, and renting a studio apartment costs at least USD 300. According to a report published on UBA’s website, “since December 2023, cumulative inflation has reached 250%, while salaries have increased only 95%, resulting in a 40% loss of purchasing power.” The government refuses to acknowledge this reality.

In 2025, the University Funding Law was approved, but Milei vetoed it. Congress overrode the veto, but this amounted to a symbolic victory. Buoyed by his midterm election success and unprecedented financial support from the United States, the president has already declared that he will not regulate or implement the law. The government’s arguments are arbitrary: it claims that the law does not specify where the additional funds for universities will come from, and that universities refuse to be audited. The universities do not reject audits—but they maintain, as established by the Higher Education Law, that the auditing body is the National Audit Office (which reports to Congress), not the General Syndicate of the Nation (which reports to the Presidency).

As for funding, the source is specified: public universities are financed through the national budget, their own institutional revenue, and the law mandates an increased allocation of GDP to education. The issue is not a lack of clarity—it is that Milei refuses to compromise on “zero deficit.” University rectors announced that they would take the matter to court, both regarding audits and the application of the law, but no developments have followed.

As mentioned earlier, the 1990s were equally harsh for universities, yet they continued operating. Traditional strikes organized by university labor unions have proven ineffective and difficult to sustain over time. Early in 2024, UBA officials stated that there were only enough funds to operate until July. Nothing happened; the university continued functioning. This year, UBA carried out a “virtual strike,” disabling access to its websites and online campuses for 24 hours. The measure was widely criticized, students opposed it, and the government announced potential legal action claiming violation of the right to education. At this point, the actors involved look like offended actresses or influencers making threats for media attention without implementing substantial measures.

Far from claiming that the Argentine university model is perfect—or defending the government’s approach—I believe it is time for universities to reflect on the institutional model they aim to sustain. The debate is not limited to whether education should remain free (which, for now, is guaranteed by law). For instance, degree programs still last five years, while in most of the world undergraduate studies last three. This leads many students to choose private universities of questionable quality to obtain degrees more quickly and enter the labor market sooner. Doctoral programs remain purely academic, built around a research system that depends on CONICET, which cannot absorb the human resources it trains. Graduation rates are low. Entry into teaching is opaque and lacks transparency.

Faced with financial strain, universities must prioritize diversifying their sources of income and building competitiveness in an expanding educational marketplace. The enemy is not only the government—it is institutional obsolescence.

What is striking is that despite the crisis, thousands of students continue to choose public universities. This year, UBA reached a record number of applicants, and its performance in controversial international rankings remains excellent. In a world where young people seem drawn to short-term courses or the illusion of living off cryptocurrency speculation, in Argentina, thousands still commit to traditional degree programs. It is for them that we cannot give up.