David Zwirner is pleased to present Rain over the river, an exhibition of new paintings by Indian artist Sosa Joseph at the gallery’s East 69th Street location in New York. This is Joseph’s first show in North America, and it follows Pennungal: lives of women and girls, her 2024 solo presentation at David Zwirner London.

A masterful colorist and storyteller, Joseph creates atmospheric paintings marked by a striking visual and psychological complexity, in which figures from her South Indian family and milieu mingle with open-ended motifs from the natural world. Oscillating between sobering reportage and intimate psychological reminiscence, her work offers an alternative approach to the artistic tradition of history painting—one in which everyday moments take on the heft of the extraordinary, and individual narratives coalesce into a richly tapestried collective history.

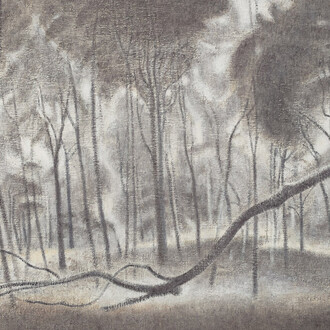

Quasi-autobiographical yet enigmatic, the paintings in Rain over the river reflect on the particularities of life in Parumala, an island village situated on the Pamba River in the South Indian state of Kerala, where the artist spent the first twenty-four years of her life. As she recalls, the banks of the Pamba would flood every year during the rainy monsoon season, forcing large populations to seek refuge in makeshift camps and public shelters. For Joseph, this rain offers an array of symbolic resonances, standing in for emotional suffering and strife as well as the physical ordeals heralded by the monsoon. In her painted recollections, however, these times of displacement and uncertainty are transformed into scenes of communal resilience in which families are drawn closer together, lovers amorously cavort, and children dance with abandon in the tent-lined streets. The artist often cloaks her compositions in moonlight, creating a hushed, eerie setting in which both strange and quotidian elements of human behavior are laid bare. Through this evocative body of work, Joseph delves into the relentless struggle for survival that animates this riverine world, exploring its capacity for fear, precarity, wonder, and beauty.

While Joseph paints largely from memory, sifting through her lived emotions and experiences, her work is also deliberately open-ended in nature; viewers are invited to participate in their own intensely personal exercise of interpretation and imagination. Approaching the painting process with an improvisatory and deeply introspective spirit, Joseph works on multiple canvases at once, repeatedly building up and wiping down layers of vivid pigment in a creative cycle that ebbs and flows not unlike the river itself. The resulting paintings—while starkly individual in their content and coloration—appear to be connected by an ever-evolving through line of physical and conceptual space.

Joseph’s compositions brim with overlapping vignettes that draw the eye back and forth, visualizing the meandering narratives and rhythms of local folktales and other spoken-word traditions. In Amma wants to finish singing before the flood drowns her (2024–2025), a woman escapes from the deluge in a boat, holding nothing but her cherished veena—a stringed instrument similar to a sitar—in her lap.

The river is similarly omnipresent in Devil’s hour, by the river (2025)—one of the artist’s largest-ever paintings—which depicts the riverbank during the desolate “devil’s hour” of three in the morning, when individuals can be seen hunting frogs and hiding among the trees. The figures seem to almost dissolve into the deep, jewel-like expanse of the river that runs across the background of the painting, leaving the viewer unsure where the human body ends and the water’s edge begins. The relationship between humans and animals forms a recurring theme in these paintings; juxtaposed with portrayals of hunters and prey—such as frog catchers, clam divers, and fishermen’s boats—are moments of tenuous coexistence: a crowd tends to the birth of a water buffalo, and a pregnant woman clutches her stomach, swaying with nausea from the sound of a rooster crowing.