‘If I were asked to characterize the present state of affairs, I would describe it as “after the orgy”.’ When French media theorist Jean Baudrillard wrote this in 1990, he could not have had any idea: Wasn’t the orgy just beginning? Wasn’t Tim Berners-Lee just finishing the earliest version of a program he called WorldWideWeb? And wasn’t 1990 also the year in which ‘Archie’ was written, a tool for indexing FTP archives—the ‘Archie’ that is logically considered the first internet search engine?

These connections are, to a certain degree, relevant to the works of Martin Gross, born in 1984, especially those in his exhibition Morning after the night before. As part of a generation who, for the most part, did not grow up with digital, let alone social media, an artist like Gross plays a pivotal role in the production, perpetuation, and interpretation of visual digital codes, last but not least with regard to image-based internet memes. And his audience clearly benefits from his knowing this role inside and out: When he integrates an outline drawing of Henri Matisse’s painting La danse, as he does in his work ‘Spirals Spiralling into Spirals’, it becomes obvious that he sleepwalks through the fragile, meme-typical balance between what is still known and what is barely conscious. Especially since, as if they were stray GIFs, Gross adds further motifs to the vortex confusion in which he lets Matisse’s dancers stagger: there is, for instance, a sketched spider web, the possible children’s book drawing of a hand gesture showing the time, or the graphic of a wormhole-like mirror application—all originals of barely traceable origin, now hyper-memes taking on a life of their own.

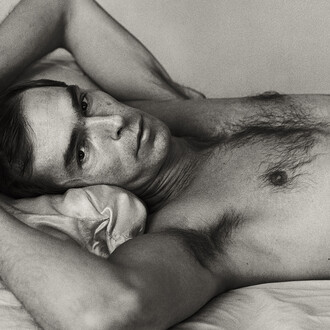

Gross’s own ‘after the orgy’—the ‘Morning After the Night Before’—typically describes the morning after a night of excess, often accompanied by a hangover. It can also refer to a moment of silence or reflection after a period of intense activity—for instance, after nighttime doomscrolling, or after the process of ‘looking for a recipe and then buying sneakers’ (Gross), the actual doomscrolling: when Orientierungslosigkeit (the abstract concept of lack of orientation) follows Signalhaftigkeit (the abstract concept of signal-holding), to bring up two terms often used by the artist.

What’s special about his work: Gross takes a detour through craftsmanship. He deliberately refers to his pictures, created in the 5:6 format of 160 x 196 cm, as ‘drawings’ (not ‘paintings’), because they are all produced with oil sticks on paper—in the world of media reproduction, this virtually embodies the analogue opposite of canvas on the one hand and screen on the other. It would be so easy for Gross to print out what he finds online and apply it to paper surfaces (or even digitally paste everything together)—this is perhaps most strikingly true of the suns with sunglasses in the work Heartbreak anniversary. As a representative of a generation who entered art school at the very moment the term ‘post-internet’ was emerging, Gross naturally knows about the intricacies of (re-)transmissions from the digital to the analogue, knows what it means to confront the concept of ‘post-meme art’, and knows about the meaning of the well-known dictum: ‘The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image.’ (using ‘poor’ in a non-judgmental way). By this point, you of course have already detected the blazing Caspar David Friedrich motif through the pixelated Sigmar Polke filter in Gross’s work Night is day. Up is down—as well as the gutted Roy Lichtenstein reference disguised as an Archie Comics speech bubble (Untitled)!

The fact that Gross initially studied graphic design is obvious at this point, reflected in the frequent text-image combinations as well as in the decision to give the exhibition its own corporate identity: the tuning flames, a visual pimping effect from the world of screeching tires, here lifted into the sky like an apocalyptic chariot of fire. In the exhibition, however, the Road to nowhere begins with a seemingly casually parked e-scooter. Released in 1985, but written by Talking Heads in 1984—the year Gross was born—their hit song is played in a generic karaoke version, inviting the audience to sing along. While the Road to nowhere is a Road of no return, it is also a Road to no regret.

(Text by Martin Conrads, 2025. Translation by Hagen Hamm)