Performances have continuously evolved in response to shifting social and cultural conditions, whether they are used to tell stories, provoke curiosity, challenge the boundaries of logic, or spark a simple thought. Popular forms of entertainment like magic shows and circuses in the 19th and early 20th centuries produced fantastical, masterful, and visually stunning settings that generally positioned the audience as a passive receiver or as someone who seemed and felt active but was actually passive.

Contemporary performance art uses similar strategies to redefine the audience’s role as active participants and co-creators of meaning by making either the performer or the spectator unsettled. Despite their differing ideological commitments and cultural contexts, the “old version” of performances and contemporary ones both use illusion and a performative space, the body as both medium and/or site of critique that traces the evolving dynamics of spectatorship.

As an important form of self-expression, these transformations observed in performance from the visually driven magic show and circus to the critically engaged contemporary performance emphasize how artistic practices respond to changing social realities, negotiating new ways to make meaning and communicate experience.

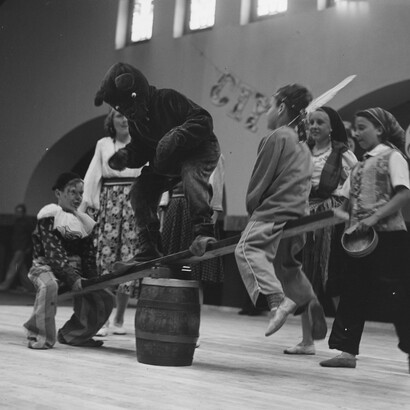

Magic shows and circuses rely on well-structured illusion systems to see the impossible and create moments of wonder. Their perfection, choreography, and hiding mechanics were not intentional deceptions but rather invitations to temporarily suspend logic and rationality. The magician's sleight of hand or the aerialist's defiance of gravity shocks the audience in a way where they accept in their mind physical perceptual boundaries were broken or can be broken. These encounters were based on feel rather than explicit instruction, with a focus on the sensory effects of visual disruption and narrative suspense. The spectator's duty was to be amazed at the impossible while staying comfortably removed from the workings of the show. Their joy and commitment invested in the unknown and incomprehension.

By contrast, contemporary performance art often repurposes illusion to interrogate rather than to enchant or conceal. Illusion becomes a conceptual device, a mechanism of interruption rather than suspension. Artists such as Sophie Calle and Tino Sehgal craft encounters that challenge conventional notions of authenticity, authorship, and presence, turning illusion reflexively upon itself to reveal the ideological frameworks that sustain it. In Take Care of Yourself (2007), Calle invited over 100 women to interpret a breakup email she received.

Calle transformed personal pain into a public artwork that resists emotional closure, diversifies the meaning, and undermines fixed readings. Similarly, Tino Sehgal, an artist who creates “constructed situations” that exist only in live encounters, designed This Progress (2010), where visitors were guided through a museum by people of different ages in a choreographed but unscripted dialogue about progress, challenging both the traditional roles of performer and audience.

The body plays a crucial role in both traditions but is inscribed with different ideological meanings. In the circus, the body is meticulously trained and disciplined. The acrobat, contortionist, or animal tamer embodies physical mastery and risk, which renders the human form exceptional. In contemporary performance art, the body is often presented in its most vulnerable form. It conveys exposure and endurance. Artists such as Marina Abramović and Chris Burden use their bodies to enact histories of trauma, violence, and gender, emphasizing social confrontation over illusion.

In Abramović’s Rhythm 0 (1974), she stood while the audience was invited to use the available 72 objects on her, including scissors, chains, and a loaded gun. The work stripped away illusion to reveal power dynamics, vulnerability, and the potential for violence within both performer and viewer. In The Artist is Present (2010), Abramović engaged in silent eye contact with museum visitors, collapsing boundaries between art and life through intense emotional presence.

Art, performance, or an art performance is not static but evolves in response to the shifting needs of society. The shift in spectatorship reflects broader cultural changes by moving from passive distance to active participation. This transformation reshapes performance aesthetics from escapist illusion to critical disruption. highlights the evolving relationship between performer and audience in a complex, fast-paced world, mirroring our current society.

Understanding these shifts in spectatorship and bodily representation also requires placing them within their historical contexts. During the 19th and 20th centuries, filled with generational and physical mass trauma, including wars, poverty, and industrial upheaval, magic shows and circuses served as necessary spaces of collective escapism and entertainment. Their illusions provided temporary relief from hardship. Today’s cultural environment is characterized less by lack of distraction than by its overwhelming richness. The pace of modern life, information flow, prolonged lifespans, and shortened attention spans cause alienation from simplicity, intimacy, and emotional depth.

Contemporary performance art often seeks to remind these not through fantasy or distraction but through direct confrontation with realities that are repressed or neglected, maybe as a trauma response, due to the lack of time to process it, etc. It insists on presence, vulnerability, and the messy materiality of the body as a means of accepting critical reflection and emotional engagement. Magic, circus, and contemporary performance art connections reveal not a drastic change between past and present but a recontextualization of performative strategies, which is responsive to shifting social, political, and psychological conditions.