Galerie Eva Presenhuber is pleased to present the exhibition Franz West: Die frühen werke / Early works with sculptures and objects from 1973 to 1992 by the Austrian artist Franz West (1947-2012 in Vienna, AT) from private collections, in particular from that of his longtime mentor, the former gallerist and curator Peter Pakesch (b. 1955 in Graz, AT) and of Galerie Eva Presenhuber. The exhibition is accompanied by a new publication, photographs by Friedl Kubelka, and film screenings by Andreas Reiter Raabe and Bernhard Riff in an adjacent space. It will be the twelfth exhibition at the gallery since the beginning of the collaboration between West and Eva Presenhuber.

In the vibrant, ever-evolving art world, where the contemporary triumphs over the past, artists, with few exceptions, fall through the cracks of attention after their deaths. Stimulated by the new, what was once so fresh gradually fades into oblivion, contrary to the notion of eternity—inevitably, seemingly naturally, and in some cases foolishly and completely unjustifiably. Such was the case with Franz West, who was awarded the Golden Lion for his life’s work at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011, a year before his death. In 2015, his unique and incomparable work entered into an exciting and insightful dialogue with that of the American artist Cy Twombly at the Museum Brandhorst. The close artistic kinship between the two artists, despite their biographical and geographical differences, was highlighted, as was the powerful influence West exerted on his contemporaries precisely because, out of an inner defensiveness, he never succumbed to the mainstream, the fashionable, or the overly conventional. Despite his international success, which began in the 1980s, and despite the 200-work celebration of his art curated by Christine Macel and Mark Godfrey at the Centre Pompidou in 2018 and the Tate Modern in 2019, it has apparently not sufficiently filtered through how far ahead of his time, and indeed our time, he was. What the philosopher Ernst Bloch wrote in The Principle of Hope about the past, which has an inherent unfulfilled surplus, is perhaps the best way to understand the Austrian’s artistically rich legacy in terms of vision, interpretation, and enjoyment.

What characterizes his oeuvre is neither active rejection nor rebellion, as has often been claimed, but rather a nonconformism rooted in his resistant character, which challenged deeply ingrained aesthetic doctrines that elevated the useless and purposeless above all else and considered practical value incompatible with art. He regarded the division between life and art as nonsensical. Precisely for this reason, and because of his penchant for “whole-body craftsmanship,” he began in 1986 to create unconventional seating furniture of all kinds as components of his exhibitions, but unlike Beuys before him with his Fat chair (1964–85). Made from prefabricated parts, covered in fabric, and altered, the seating is strange in the sense that it subtly transcends the banality of everyday objects. Instead of following a plan, West relied on spontaneity. The furniture sculptures were not only meant to invite visitors to actually sit down, because he wanted to pierce, break and tear down the wall between viewer and art, but also because he was very interested in the physical experience of the works with the buttocks, through touch and feeling. Reducing perception to the visual was too one-sided and insufficient for him, so he expanded it to include the tactile.

Moreover, West never saw himself as a genius, but rather as someone who, although he never used the currently fashionable terms “collective” and “participation,” collaborated with others when he felt he could not accomplish something alone. When he felt the joyful desire to add color to his previously neutral white, amorphous sculptures modeled from papier-mâché, his “shyness of color” and self-doubt about his ability to work with color were so strong that he asked fellow painters such as Herbert Brandl, Heimo Zobernig, and Albert Oehlen for help in adding the finishing touches to his works with colorful paint until, years later, he felt confident enough to “stand in the colors” himself (Handke on Cézanne).

He was a loner, a unique individual, and an innovator, yet he sought collaboration with fellow artists and audience participation, for only then did his creations become complete works. All in all, he was not an artist in revolt, as he seemed, but a philosophically knowledgeable, immensely well-read autodidact who read Ludwig Wittgenstein, Sigmund Freud, Jacques Lacan, Martin Heidegger, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and many others in his own idiosyncratic way and in his own sense. He welcomed Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea that “if an illusion helps you in life, then it is reality,” as well as David Hume’s idea that “there is no causality, but rather more or less coincidences or series of coincidences to which everything boils down,” and Wittgenstein’s statement that “everything we see could also be different.” His “sense of possibility” was more pronounced than his “sense of reality” (Robert Musil). Basically, West created his works in parallel with his philosophical reflections.

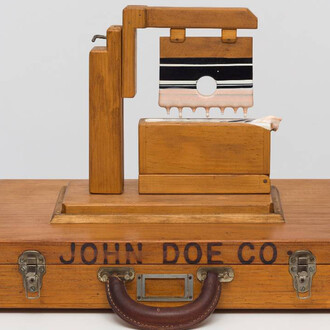

He was a collector not only of art, but also of rubbish, discarded or thrown-away objects such as bottles. Rather than elevating his found objects to the status of collectibles, which, decontextualized and displayed in vitrines, mutate into something valuable, he used them in combination with others as raw materials or starting points for creations covered with a layer of plaster, so that they appear fragile and often no longer reveal what they originally were. With these works, which he called “Adaptive” or “Passstücke,” he sought to deprive the objets trouvés of their namability and definition. Above all, the amorphous “Passstücke” are meant to be picked up by us, played with, actively engaged with, and moved through space. When placed on the body, they influence posture, gestures, and motor skills, much like a straitjacket, the wearing of which makes us aware of how much we determine ourselves. Referring to Freud, whom he read as a twenty-year-old, West materialized and visualized full-blown neuroses. Man is “a prosthetic god,” he said. If neuroses could be seen, they would look like this. Here, the inner is turned outward and materialized so that it can be seen, felt, and experienced by everyone, with a dash of subversive humor, as in his painted collages of old photographs on newspaper.

(Text by Heinz-Norbert Jocks)

![Karel Appel, Le coq furieux [The furious rooster] (detail), 1952. Courtesy of Kunstmuseum Bern](http://media.meer.com/attachments/de322f88933729d2014dc4e021d4a6694046a744/store/fill/330/330/c26a6c5ef5e2ed397d4a2e9bc00ac739c40ba8384f45f9ce1ed85adba600/Karel-Appel-Le-coq-furieux-The-furious-rooster-detail-1952-Courtesy-of-Kunstmuseum-Bern.jpg)