Current affairs note: At first glance, this text seems futile in light of the recent attack by Israel and the US on Iran, one of the new members of the BRICS+. Read carefully, however; this text conceives such an attack as perhaps the last gasp of the unipolar world dominated by the US and heralds the hope that may follow its collapse. But as the old has not yet completely disappeared and the new has not yet fully emerged, we will witness during this transition period the monstrosities of which Antonio Gramsci spoke. The attack on Iran is one of them.

A conceptual clarification

Ideology is a set of illusory ideas considered necessary to support or make the unbearable bearable. The unbearable always has to do with contested (not naturalized) inequality and discrimination within a given community. Religion is a set of ideas about the transcendence of this world (a final transformation in this or another world), accompanied by the means to achieve such transcendence, which include regulations of the body (especially sex) and of coexistence. It often has the same function as ideology.

Wisdom is a set of ideas based on the experience of the unbearable that offers alternatives that are almost always unpopular with those in power. It is a process of personal cultivation to approach this ultimate reality (the heaven of Confucius) with the aim of distinguishing clearly between good and evil. In this text, these three concepts are understood as porous entities with multiple bridges between them in the lives of people.

Since the 15th century, the dominant ideology in the world has been Eurocentric, and its dominance corresponds to the rise of Western colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism. This ideology is complex, but its fundamental pillars are liberalism (free trade, individualism, private property, the state and law as monopolies of legitimate violence, and liberal democracy), modern science as the only rigorous knowledge, rationalism (as pragmatic rationality), universalism, linear progress, human rights, and secularism. It is characteristic of the dominant ideology (precisely because it is dominant) to both reveal and conceal.

It conceals above all the practices that contradict it, which is why it is often adopted by the dominated social classes and groups, whose interests it most denies. For this reason, domination is exercised both through violence and through the consent or passivity of the dominated. In certain circumstances, the dominated can tactically or selectively appropriate the dominant ideology and use it in their resistance struggles against domination. This has often been the case with the ideas of human rights and democracy.

After five centuries of domination, Western colonialism-capitalism-imperialism is showing signs of decline. This domination has always been partially contested (communism, the labor movement, political liberation of the colonies, Third Worldism), but it has always prevailed. Until today. The vertigo of war hanging over the world is one of the signs of the irreversible decline of Western domination. The other is the emergence of the BRICS+. Western capitalist accumulation faces a crisis that is directing its search for profitability towards non-productive areas, whether financial speculation or the arms and surveillance industries. The casino economy and the death economy are joining hands in a last-ditch attempt to avoid or postpone the final collapse.

The BRICS+

Meanwhile, a non-Western capitalist accumulation is emerging on the horizon with unprecedented vigor, led by countries that were either European colonies or were humiliated, dominated, or invaded by Western powers over the centuries. I am referring to the BRICS and, above all, the BRICS+, which, in addition to the countries that make up the acronym (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), now include eleven major emerging economies and are on the verge of integrating many other countries. They now represent 49.5% of the world's population, around 40% of global GDP, and 26% of global trade. They have already surpassed the group of most developed countries, the G7, which represents 30% of global GDP and 10% of the world's population. Brazil took over the presidency of the group in January and chose as its theme “Strengthening cooperation between the global South for more inclusive and sustainable governance.”

Unlike what happened with the Third World movement (born at the 1955 Bandung Conference), the choice between capitalism and socialism is not up for debate. What is at stake is a non-Western capitalist alternative that can compete effectively with Western colonialism-capitalism-imperialism. In other words, what is at stake is the creation of a multipolar world, where the Western world is invited to coexist on an equal footing, for the first time in the last five centuries, with the non-Western world. This does not mean that all countries belong to the non-Western world with the same intensity (just think of Brazil), but the dominant orientation is non-Western.

As the president of South Africa said during his country's presidency of the BRICS in 2023, “We don't want to be told what is good for us; we want the fault lines of the architecture of global governance to be redrawn, reformed, transformed... We want to participate in the process of creating a more just, inclusive, and multipolar world community.” I have argued that the expansion of the BRICS and the consequent construction of a multipolar world can be a factor for peace, insofar as they can contain the drift toward war in which the Western world is immersed, now dominated by a new “axis of evil”: the US, Europe, and Israel.

Several questions arise, however. If they do not propose socialism, will the BRICS not end up reproducing the colonialism-capitalism-imperialism matrix that has characterized the Western world for centuries, a matrix that, in a nutshell, has been characterized by unequal relations (plunder, deception, bad faith) between the center and the periphery? Will the ideology that gave cohesion to the modern Western era have a corresponding ideology in the BRICS? And if so, what ideology will that be? Given the historical experience of these countries, will they be interested in a different ideology or a new concept of ideology? Can capitalism coexist with various ideologies, a question that arose in the 1980s with the economic emergence of Japan and South Korea?

Enter Confucianism

The dominant ideology of the Western world was largely produced by the dominant countries, especially England and France. In the BRICS, the dominant country is China. Before enlargement, China accounted for 70% of the wealth produced in the BRICS.

The Chinese economy is five times larger than India’s, eight times larger than Russia’s, nine times larger than Brazil’s, and forty-three times larger than South Africa’s. Before enlargement, the ideological trajectories of the different countries were extremely heterogeneous: imperialism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Marxism in China; Hinduism (swaraj, swadeshi), Buddhism, and Islam in India; Western Christianity, developmentalism, and sovereignty (permanent tension between sub-imperialism and dependency theory) in Brazil; imperialism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity, primitive communism, and Marxism in Russia; and African humanism, nationalism, Ubuntu, and apartheid/anti-apartheid in South Africa. After enlargement, the Islamic component expanded enormously.

But above all, the diversity of ideologies increased. Just think of ancient Egypt and Persia (Zoroaster). Needless to say, these designations contain within them enormous internal diversity, which is sometimes antagonistic.

Whatever the importance of the dominant ideology, I will start from the assumption that the dominant ideology is the ideology of the dominant country and that, unlike the Western world, the BRICS countries—as their leaders have said in multiple statements—wish to bring about a change in the world system in line with the new ideology. Today’s China is officially Confucian. The first Confucius Institute was opened in Seoul (South Korea) in 2004. There are now 548 Confucius Institutes around the world where the Chinese language and culture are taught, and cultural events and educational exchanges are organized.

Cautions proposed by the epistemologies of the south

It is worth asking whether the concept of ideology is adequate to describe dominant ideas in civilizations much older than Western civilization, especially since such civilizations lived in isolation for centuries. In the case of Confucianism, we are talking about a philosophical tradition that is over 2,500 years old. When these civilizations came into contact with Western civilization, they were placed in a position of inferiority imposed by the superiority of Western weapons. Furthermore, what we call Western culture (its pillar of classical Greek antiquity) would not exist if it had not been transmitted to us by Islamic culture during its heyday (Baghdad, 9th-11th centuries, and Al-Andalus, especially in the 11th-13th centuries).

If we consider Confucianism, its author, Confucius (born in 551 BC), like true sages in general, was not well accepted in his time. He was briefly recognized by the rulers, forced into exile, and followed by a small number of disciples. Over the centuries, Confucius rivaled Taoism (Lao Tze, another enigmatic sage who experienced exile and only wrote his work, Tao Te Ching, because he was forced to write it as a condition for having permission to leave the state), and was sometimes ardently accepted and sometimes violently rejected.

Let us look at the most recent period. It should be noted that what we know of Confucius (as with Socrates) is what his disciples recorded. In this regard, his great disciple Mencius (4th century BC) is particularly important. In the 2nd century BC, Confucianism was adopted as the official ideology of the Chinese empire. Its popularity suffered many setbacks over the centuries, but it was not radically challenged until the 20th century AD. The long Qing dynasty (1644-1911) collapsed largely due to the Opium Wars of the 1840s and gave rise to the Republic of China, which still survives today in Taiwan. On the mainland, from 1920 onwards, the struggle between the Communist Party (in which Mao Zedong would distinguish himself) and Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Party would last until the Communists' victory in 1949.

Communism and Confucianism

The most radical challenge to Confucianism began in the early decades of the 20th century with the proclamation of the Republic in 1912. While some considered Confucianism to be the reason for China's backwardness—its inability to become a modern nation-state—others believed that Confucianism could be renewed to adapt to the new times (neo-Confucianism). The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949 under the aegis of the Chinese Communist Party.

The first point to note is that Confucianism, although very ancient in China, is very recent in the ideological repertoire of the People’s Republic of China. Indeed, it can be said that in 1949, the communists considered Confucianism to be extinct, like any other reactionary ideology. Confucianism was a “feudal ideology.” The second point (not contradictory to the first) is that Chinese communism must be understood in the context of a civilization shaped by Confucianism.

This means, first of all, that the prosperity or ruin of the country depends greatly on the virtue or vice of its rulers and that the government must seek social harmony—between the need for government, since individuals only seek to satisfy their personal interests (legalism), and the idea that human nature is good and sociable and that government, as something separate from society, should disappear (Taoism). A complex and even contradictory mixture of hierarchy and egalitarianism, conflict and moderation, and authority and consultation/moderation/tolerance.

Confucius conceived of society as a family in which filial love (respect for the elders) and the authority of the father are fundamental to maintaining social harmony. Education is fundamental in Confucianism, as is the moral integrity of rulers, who must also be educated to follow the principles of Confucian good governance.

The just revolt against bad rulers is present in Confucius, and the idea of a hierarchical society coexists with a long tradition of peasant egalitarianism, often associated with rebellions based on associations of many kinds, many of them secret (e.g., the triads). One such rebellion took place in Hunam in 1926-1927 and was witnessed by the young Mao Tse Tung, certainly an influential experience of his youth reflected in the version of Marxism he would later develop: peasants as a revolutionary force, support for rural communes, and a mass line based on the experience of peasant guerrilla warfare.

Mao, like Confucius, believed that human nature was essentially good and that education was fundamental to its flourishing. Like Confucius, Mao believed that the superiority of government lay in a moral superiority based on the “golden mean”—the principle of balance between extremes. As in Confucius, Mao’s “new man” emerges from a society founded on community solidarity. But as is almost always the case with ideologies, opposition to Mao also claimed fidelity to Confucianism.

The cultural revolution and the post-cultural revolution period

The Cultural Revolution (1966-69/76) marked yet another end to Confucianism. It was invoked only by those who opposed the Cultural Revolution, emphasizing how Confucius placed humanity and justice above conflict. And although for Mao the opposition was less Confucian than revisionist, that is, made up of followers of Khrushchev's Soviet communism, the anti-Confucian campaign would eventually prevail: Confucius became the number one enemy of communist China.1

Shortly after Mao's death, the main executors of the Cultural Revolution (the Gang of Four) were arrested. With Deng Xiaoping, the rapprochement with the West coincided with the gradual rehabilitation of Confucianism (temples, monasteries, permission to study Confucius), considered an important part of traditional Chinese culture. Particularly after the Tiananmen massacres (1989), the questioning of communism created a void that was gradually filled by Confucianism. A new wave of “Confucius fever” emerged.3

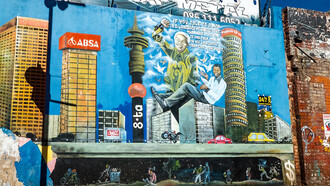

In 2006, Yu Dan's book “Reflections on the Analects” sold three million copies in four months. It is an aseptic view of Confucius in which the critical and rebellious aspect against unjust governments disappears. Over the last two decades, Confucius has been used to emphasize three ideas that the CCP has been promoting: patriotism/nationalism; China as one of the world’s great civilizations, and a harmonious society as a condition for stability (and, consequently, the discouragement of dissent). It was in this context that the Confucius Institutes emerged in 2004.3

Confucianism and the BRICS

What kind of Confucianism will China bring to the BRICS? I am sure it will be Yu Dan's bland, sentimental version. Perhaps with an emphasis on tolerance, compromise, harmony, mutual respect, observance of agreed rules, and self-control, which in itself is very necessary in the war-torn, anarchic, dystopian, and self-destructive world that the world under US influence is entering. For this reason, and because of the muscular multipolarity promised by the BRICS, what I said above about the BRICS as a factor for peace is justified. And, in fact, the BRICS have refused to follow the Western position on the war in Ukraine and on sanctions against Russia, are taking important steps to ensure that the world economy does not depend on the dollar—the basis of US hegemony and blackmail power—and are consolidating a development bank whose operating logic (in light of official documents) is different from that of international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank.

But will this be enough to create a sustainable alternative to Western capitalism? I very much doubt it. To justify my doubts, I turn to Confucius. One of Confucius' famous aphorisms says:

No one is free from making mistakes. The important thing is not to make the same mistake twice.

Western capitalism: the way in which Western capitalism was implemented had, among many other characteristics, the combination of capitalism with colonialism, that is, with the harsh inscription of an abysmal line in the human community: the line that separates human beings treated as fully human (citizens, European colonists) from human beings treated as subhuman (colonized peoples). This devaluation not only justified the ontological degradation of a large part of the world's population but also justified slavery, land theft, dispossession, super-devaluation of labor, racism, deception, and unequal contracts. All of this consolidated the structure of the world system between a center and many peripheries and semi-peripheries characterized by permanent transfers of value from the peripheries to the center, that is, from the impoverished majorities to the enriched minorities. Until today.

BRICS capitalism: the rhetoric of international relations within the BRICS—South-South cooperation—is totally opposed to the Western capitalist system. But what about in practice? Authors who have closely studied cooperation agreements between the BRICS and their peripheries have drawn attention to the fact that, despite the rhetorical difference, the concrete clauses reproduce many of the characteristics of the unequal relations that have always characterized Western capitalism.4 Vishay Prashad speaks of a “neoliberalism with Southern characteristics,” and Patrick Bond has resorted to the concept of sub-imperialism, coined by the great Brazilian sociologist Ruy Mauro Marini to characterize the relations of the BRICS with their peripheries.

In the theoretical framework I have been developing, capitalism is not sustainable without colonialism. I believe, however, that the history of the BRICS is still in its infancy and that intellectuals who support them must avoid premature judgments and be prepared to revise their theories, rather than dismissing practices that contradict them. In any case, a hermeneutics of suspicion about the future practices of the BRICS is fully justified as a form of prudent thinking, much in the manner of Confucius. It is a matter of insisting that those who deal with international cooperation promoted by the BRICS always bear in mind Confucius' aphorism: “Do not do to others what you do not want them to do to you.”

Confucius and the epistemologies of the South: an ecology of knowledges

For me, the most promising aspect of the BRICS+ project lies in the opportunity it gives the people who make up the BRICS+ (not necessarily the governments) to build a much broader conversation about humanity than the Western world has provided over the last five centuries. A broader and different conversation. The Western world has always conceived of the cultural, ethno-racial, and epistemic diversity of the world within a matrix of hierarchical differences. Difference is always recognized as superior or inferior, with the global South always being the inferior side of difference.

On the contrary, if the BRICS+ countries are aware of this history (as Confucius rightly recommends), they can now promote non-hierarchical differences, a new type of intercultural diversity. If this conversation about humanity is encouraged, it contains within itself valuable incentives to give credibility to anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist alternatives. This will be possible if Confucius’ teachings are articulated with the non-Eurocentric wisdom, worldviews, and philosophies that survived the epistemicide imposed by Western modernity.

This is not about looking at the past with nostalgia. It is about looking at the past in order to see the future. This idea is as central to Confucius as it is to the philosophy of African peasants and the indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples of Latin America. What is at stake is the construction of what I call anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist ecologies of knowledge. I identify some of the most promising ideas:5

The virtues in Confucius include humanity/benevolence, honesty/integrity, knowledge/wisdom, fidelity/respect for elders, and prudence/observation of rituals.

Humanity/benevolence without abyssal lines is present in all non-Western wisdom. It consists of treating all humans in a fully human way. It is at the heart of the Ubuntu philosophy of Southern Africa (“I am because you are”).

Knowledge/wisdom is the condition for promoting moderation between extremes and following the Way (“those who do not study have no right to speak”). Fidelity/respect for elders (the other side of filial love) is the principle of cohesion in communities that felt threatened by Western colonialism and still today sustain family solidarity on the brink of the chaos of survival. Prudence/observance of rituals aims to build harmony without blind obedience. Today, observance of rituals can be both respect for the principles of democracy, the rule of law, and constitutional and procedural guarantees, as well as respect for international treaties and the primacy of peaceful coexistence.

We stand helplessly by as the far right seeks to destroy these rituals, for example, by resorting to insults and physical violence in parliaments. At the international level, we are equally helpless in the face of the most brutal violations of international law and peaceful coexistence, from the genocide in Gaza to the attack on Iran (one of the new members of the BRICS, it should be remembered).

Confucius+, that is, intercultural Confucianism in an ecology of knowledge with the knowledge of all the peoples that make up the BRICS+, may well be an ideological tool to effectively combat these designs. Confucius said to his disciples, “An oppressive government is more violent than a tiger.” If the BRICS take this philosophy seriously, they will be equipped to fight against the fury of war that dominates the Western world today. A fury that invented weapons of mass destruction to destroy Iraq and, twenty years later, invented the Iranian atomic bomb to destroy Iran.

According to Confucius, the goodness of human nature is given to humans by heaven, but heaven is not a personalized god. It is a semi-naturalized entity, an ultimate reality. Is Confucian heaven very different from Pachamama, the mother earth of the indigenous people of Abya Ayala? Or from Spinoza's natura naturans? Respect for heaven conceived as transcendence of the human embodied in overly human nature may be the solution to the ecological collapse towards which we are heading.

Confucius is the philosopher of self-control, prudence, and not speaking before investigating. When his disciples asked him what knowledge was, Confucius replied a century before Socrates and a millennium and a half before Nicholas of Cusa, “It is knowing what I know and knowing what I do not know.”

Confucius+, an ecology of knowledge built from Confucianism, with Confucianism, with other ways of knowing from the Global South, and sometimes against Confucianism, is a project for the future based on a solid foundation laid 2,500 years ago. It is an ongoing project that must include all the achievements that have been consolidated over the centuries, many of them promoted by the Western world. For example, the debate on women’s rights is now a topic of discussion within Confucianism. While Confucius’ prejudice against women is criticized, attention is drawn to his ethics of care, which is claimed by feminists.6

Another debate with great intercultural potential focuses on the relationship between Confucian values and human rights. Confucianism makes it possible to eliminate the individualistic bias underlying human rights, which are said to be universal but are in fact Eurocentric in origin, and, without eliminating them, to strengthen the economic, social, and cultural rights currently under attack by neoliberalism.7

For all these reasons, BRICS+ is not a lost cause. It will only be so if the people who comprise it squander the opportunity to found a new non-Eurocentric internationalism based on a new education grounded in the epistemologies of the South. Perhaps Confucius’ greatest lesson is this: “Love of good without love of education ends in stupidity.”

References

1 On Confucianism and the Cultural Revolution, see Tong Zhang and Barry Schwartz, “Confucius and the Cultural Revolution: A Study in Collective Memory,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 11, nº 2 (Winter 1997), 189-212.

2 A brief overview of Confucianism throughout the centuries can be found in Jonathan D. Spence, “Confucius,” The Wilson Quarterly, Vol. 17, no. 4 (Autumn, 1993), 30–38. See also Jin Wang and Keebom Nahm, “From Confucianism to Communism and Back,” Journal of Asian Sociology, Vol. 48, no. 1 (March 2019), 91-114.

3 On the debate generated by Confucius Institutes in the Western world, see, for example, Heather Schmidt, “China’s Confucius Institutes and the ‘Necessary White Body’,” The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers canadiens de sociologie, Vol. 38, no. 4 (2013), 647-668; Marshall Sahlins, “China U.,” The Nation, 297 (20), 2013, 36-41; Marshall Sahlins and James L. Turk, “Confucius Institutes,” Anthropology Today, Vol. 30, no. 1 (February 2014), 27-28; and Stambach, A. Confucius and Crisis in American Universities: Culture, Capital, Diplomacy in U.S. Education. London: Routledge, 2013.

4 See the bibliography cited by Laurent Delcourt, “BRICS+: une perspective critique,” in Alternatives Sud, XXXI, 2024, 1, dedicated to the theme “BRICS+: une alternative pour le Sud global?”

5 All references to Confucius are taken from the Analects in the edition by Arthur Waley. New York: Vintage Books, 1938.

6 See Xiongya Gao, “Women Existing for Men: Confucianism and Social Injustice against Women in China,” in Race, Gender & Class, Vol. 10, nº 3 (2003), 114-125; Anna Sun, “The Emerging Voices of Women in the Revival of Confucianism,” in Confucianism as a World Religion: Contested Histories and Contemporary Realities. Princeton: PUP, 2013; Daniel A. Bell, “Reconciling Socialism and Confucianism? Reviving Tradition in China,” Dissent, Vol. 57, nº 1 (Winter 2010), 91-99.

7 See, for example, May Sim, “Confucian Values and Human Rights,” in The Review of Metaphysics, 67 (2013), 3-27.