In Cali, no one makes art with the latest update. This city’s visual history has been written in beta—using recycled materials, glitched images, and blown-out sounds. Our aesthetic is bootleg, out of necessity and by choice.

Hechizo—that word that names an act of magic, but in Cali has come to mean the fake, the imperfect version, the failed aspiration—functions here as an ontological category. There is no original—only incomplete simulations, jammed with interference, obstacles, and noise. The outskirts of pirated internet never receive full references; what arrives are the games. Cracked games, glitchy ones, patched and looping NPCs in a tautology of images feeding off one another.

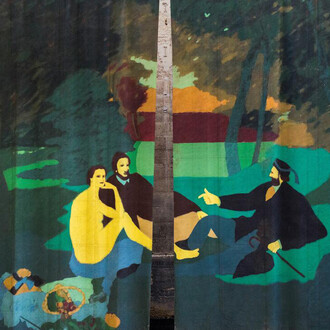

In Hechizo, Johan Samboni proposes a visual metaphor of marginality, where surface and resolution are not technical problems but political reflections. Low resolution becomes a metaphor for vision from Cali’s east side: it’s not about painting with fidelity to the reference, but from the experience of living among copies and simulations. This material essay—built from objects that clash in scale, smoothed-out textures, and vinyl landscapes—functions as an archive, where each piece is part of a software rendering a territory. It all gestures toward an uncomfortable idea: what we consume as reality is, to a large extent, decoration.

Let’s think of each pixel as a minimal unit of representation that, by nature, signals lack: an attempt to rebuild the image with the least amount of information possible. And that has historically defined the representation of certain bodies and geographies: with scarce data, no context, and from a distance. In Hechizo, the materials of urban self-construction—roof tiles, cement, cans, reused paint—operate like physical pixels; fragments used to assemble a stage set of desire. Maybe completeness isn’t an option. But there is patchwork. There is invention.

In this universe of shapeshifting surfaces and fictionalized flesh, everything is scenography. But it’s precisely there, on that surface, where the politics of representation takes place, and to paint it is to draw something akin to a cartography of power. Johan knows that the images of marginality don’t necessarily emerge from the margins themselves, but from a center that needs them as a backdrop.

(Text by Ana Cárdenas)