Celadon ceramics were first created during the Koryo Kingdom (918–1392 AD). As the 14th century drew to a close, the once-celebrated practice of crafting these radiant vessels began to fade. Production came to a halt until the 1880s, when archaeological discoveries reignited interest in the form. Initially led by Korean collectors and historians, this revival soon drew the attention of Japanese, American, and European collectors alike. Korean celadon wares reached a zenith of popularity during the 1910s, which, perhaps unsurprisingly, led to a decline in their availability in the decades that followed.

Celadon ceramics are imbued with symbolic and cultural significance—not to mention their sensuous visual beauty. Even British colonial officials recognized their allure, as evidenced by British Vice-Consul William R. Carles’s 1888 account. Carles recalled how celadon wares were insolently excavated from tombs near Kaesong, where members of the Koryo royal family had been buried:

“In the winter after my return to S[e]oul [in 1884–1885] I succeeded in purchasing a few pieces, part of a set of thirty-six, which were said to have been taken out of some large grave near Songdo [Kaesong].”

Traditionally, Korean celadon ceramics were decorated with sanggam inlay patterns, using alabaster and ink-black pigments to carve and stamp motifs of cranes, clouds, ducks, lotuses, willows, and other forms rich in symbolism. The celadon works in this Kate Oh gallery group exhibition were produced at the Buan Official Kiln, a state-operated ceramics center during the Goryeo dynasty. As a government-run kiln, Buan was responsible for creating high-quality wares for royal and official use, showcasing the peak of celadon artistry through refined inlay techniques and elegant jade-green glazes.

Kate Oh’s group exhibition brings together four artists—INYoung, Jeon Yoonjae, Kim Mun-sik, and SoYun—offering a broad and compelling interpretation of celadon, both materially and conceptually. As is characteristic of Kate Oh’s curatorial vision, the show also makes space for progressive modernist tendencies.

In Young’s azure hanji works, for instance, recall Jiří Kolář’s variegated collages. The artist draws on the curves and glazes of celadon pottery, with its undulating forms and dynamic silhouettes. This is particularly evident in abstract pieces such as In Between the Grains, where mother-of-pearl scintillates across hanji and cut wood. The works engage significantly with the form of the object without being tethered to its material presence.

Jeon Yoonjae’s mixed media works on cotton are similarly sensuous. One detects the influence of Goryeo celadon in their verdant and aquamarine glazes. Especially captivating is the Watermountain series, where striated peaks rise like crystalline waves in cerulean and turquoise hues—each crest sharply rendered into brilliant relief.

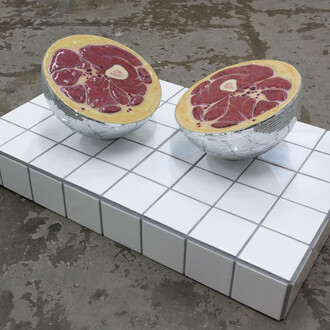

Kim Mun-sik’s celadon openwork pieces take inspiration from traditional Goryeo motifs. His sophisticated, delicate surface patterns form arabesque rivulets, as seen in his exquisitely crafted pencil case. With remarkable sensitivity to local tradition, Mun-sik manipulates light across intaglio and bas-relief surfaces to striking effect.

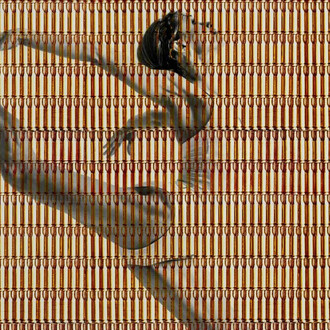

Finally, SoYun’s pigment-on-hanji works offer a contemplative interplay between natural and industrial motifs. Rendered in soft natural pigments, the pieces synthesize organic and constructed forms. Like In Young, SoYun emphasizes curvature and engraved patterning, approaching Goryeo celadon as a pure form open to contemporary interpretation. Works such as A morning that listens and The temperature of dawn arrange botanical forms in gentle harmonies. The Merged into triptych begins with a Friedrich-esque arboreal landscape, shifts through the rhythm of ocean waves, and concludes in a cityscape veiled in smog—an allegorical transition from nature to urbanization.

Collectively, these works—like Kate Oh’s exhibition as a whole—approach celadon with both reverence and reinvention, offering fresh perspectives on one of Korea’s most storied traditions.

(Text by Ekin Erkan)