Art is the bridge between the tangible and the intangible, a reflection of human consciousness as it evolved over millennia.

In previous explorations of the Journey of Art, we have traced the emergence of visual storytelling, music, clothing, and even the domestication of animals, all vital in shaping the human experience. Now, we turn to another pivotal development: the formation of structured society.

Early humans did not always move in isolated groups; necessity urged them to form small collectives, bound not by blood alone but by mutual survival. Safety, hunting, and resource sharing demanded cooperation, and through this, the first structured communities were born.

But how did they maintain harmony?

How did they avoid chaos?

And most intriguingly, could the same cognitive faculties that led to artistic expression have played a role in the evolution of leadership and societal organization?

The necessity of small group formations

For early Homo sapiens, the world was harsh and unpredictable. Unlike their Neanderthal counterparts, who were physically robust, early modern humans compensated with adaptability and social intelligence. They were not the strongest nor the fastest, but they excelled at communication, planning, and learning from the environment.

At first, small bands likely consisted of extended family units. However, as these groups grew and encountered others, their survival depended on forming cooperative alliances. The benefits of such collectives were evident:

Safety in numbers: a lone individual was vulnerable to predators, but a group could defend itself more effectively.

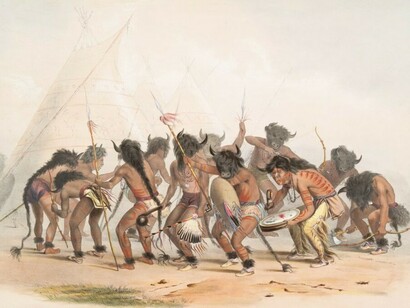

Shared hunting efforts: coordinated strategies in hunting larger prey, such as mammoths or bison, increased efficiency and success rates.

Resource management: groups could share food, shelter, and even knowledge about seasonal changes or medicinal plants.

Yet, larger groups also introduced challenges. Conflicts over food distribution, decision-making, and individual roles had to be addressed for stability to persist.

Creating harmony within the group

The most crucial element of any society, ancient or modern, is the ability to maintain harmony. Without an agreed-upon system of conduct, disputes could escalate, threatening the survival of the collective.

But how did early humans ensure order without formal laws or written language?

One answer lies in symbolic communication and shared narratives.

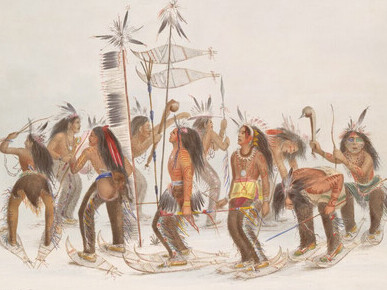

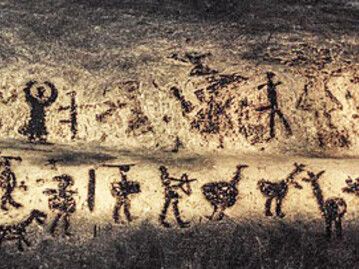

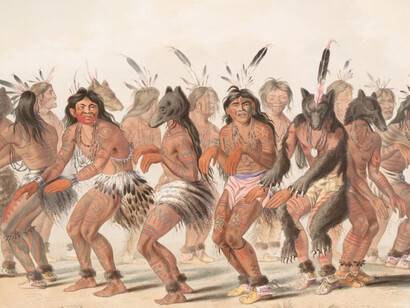

Cave paintings, carvings, and oral storytelling helped establish group identities and moral codes. These early artistic expressions served as the first “cultural contracts,” reinforcing values such as bravery, cooperation, and respect for nature.

Additionally, rituals likely played a role in uniting individuals under common beliefs. Simple ceremonies, perhaps tied to successful hunts or seasonal migrations, would have solidified group cohesion. This gradual development of shared customs and traditions would become the foundation for structured societies.

The emergence of leadership structures

The next logical step in human organization was the establishment of leadership. When disagreements arose, who would lead the hunt, where to migrate, and how to resolve conflicts? There needed to be a central decision-maker.

The question, then, is how these leaders emerged. Unlike in modern political systems, early leadership was likely based on merit rather than inheritance. The leader was not necessarily the strongest but rather the most strategic, the wisest, or the one with the greatest ability to unify people.

Possible ways in which leadership was determined:

Elders as decision-makers: wisdom gained from years of experience may have granted older members authority in guiding younger generations.

The best hunter as a temporary leader: strength and skill in hunting could have determined leadership, at least for specific tasks.

Consensus-based selection: a form of early “election” where the group collectively acknowledged the most capable leader.

This rudimentary form of governance marks an essential shift: human groups began choosing structure over chaos and order over disarray.

Cognitive reasoning and the role of art

What makes this transition truly fascinating is how it may have been influenced by the same cognitive advancements that birthed art.

Art is not merely an aesthetic pursuit; it requires imagination, foresight, and problem-solving.

The very act of creating a painting or carving involves abstract thought: an artist must envision the final result before making the first mark.

This kind of premeditated thinking, this ability to translate thought into action, is the foundation of structured decision-making.

Just as an artist plans their composition, a leader must plan group survival strategies.

Just as a sculptor visualizes form before carving, a hunter must predict animal movements.

Just as music requires rhythm and coordination, societal harmony requires balance and structured roles.

Could it be that the same logical and creative faculties used to make art also paved the way for human governance?

The answer lies in the brain’s evolution.

As early humans engaged in artistic expression, they strengthened their prefrontal cortex, the part responsible for logic, organization, and social behavior. Over time, this may have enhanced their ability to make structured decisions, leading to the birth of leadership and governance.

Conclusion: art, order, and the human mind

What began as a means of survival, forming groups for safety, soon evolved into structured societies.

Leadership emerged not from brute strength but from intelligence, wisdom, and the ability to unify people under a common cause.

This transition was not separate from art but rather a direct extension of the same cognitive growth that enabled humans to paint, sculpt, and create music.

If art is the language of the soul, then society is its living expression.

The earliest human groups were not just collections of individuals but collaborative minds, shaping a world that extended beyond mere existence.

And at the heart of it all, there was always the need to tell stories, to express, to create, because structure, in its purest form, is itself an art.