Art, at its core, is an act of perception. Long before the written word, before structured society, and even before the first great monuments, humans observed. They watched the rhythms of the natural world; the shifting of the seasons, the migration of animals, the way a bison turned its head—and they sought to capture these truths through art.

Two remarkable sculptures from prehistory exemplify this early human attentiveness: the Bison Licking Its Back and the Swimming Reindeer.

Each, in its own way, reveals how early artists moved beyond mere representation, embedding layers of movement, behavior, and ecological awareness into their work. In them, we see a crucial step in the evolution of art: where humans not only depicted animals but also told their stories.

The bison licking its back : a study in movement

Discovered in the Tuc d’Audoubert cave in France, the Bison Licking Its Back is a masterpiece of prehistoric art.

Created from a single piece of unbaked clay, this sculpture portrays a bison in a moment of naturalistic motion, its head turned backward, its tongue extending to groom itself.

The precision of this piece is remarkable. The artist paid close attention to musculature, the curvature of the spine, and the soft folds of skin where the bison's neck twists. This is not a static image of an animal standing still; it is a snapshot of a moment in time.

The artist captured not only the physical form of the bison but also its behavior, something that required careful study and understanding.

Why was this important?

The bison was a crucial part of the prehistoric ecosystem and a primary source of food, materials, and perhaps even spiritual significance for early humans.

By sculpting it in such a detailed and natural pose, the artist demonstrated a deep familiarity with the animal’s habits. This was not just art; it was knowledge, passed down through craftsmanship.

The choice of medium is equally telling. Unlike cave paintings that could last for thousands of years, this sculpture, made from clay, was fragile and likely meant for temporary viewing.

Was it a form of ritual art, an offering, or a lesson for younger generations on how to observe nature?

The answers remain unknown, but one thing is certain: the artist was more than a creator; they were a keen observer of life.

The swimming reindeer: the language of migration

Just as the bison captures movement, the Swimming Reindeer sculpture reveals an understanding of seasonal rhythms.

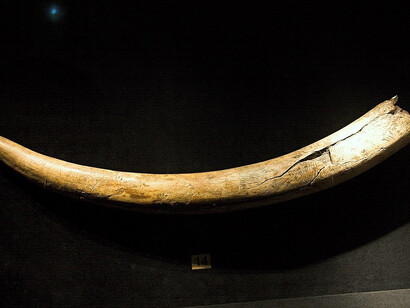

Carved from a single piece of mammoth ivory and dating back nearly 13,000 years, this work depicts two reindeer swimming in tandem. The detail is striking. The female reindeer leads, her body stretched forward, while the male follows behind.

Their antlers are fully grown, a detail that, to the untrained eye, may seem incidental. However, this small artistic choice tells a much larger story.

Reindeer grow their antlers to full size only during migration season. The fact that the artist chose to depict them in this state suggests a significant level of knowledge about reindeer behavior.

This is not just an image of two animals in water; it is an observation of a specific moment in the natural cycle.

The artist recognized that reindeer swam during migration, that females often led the way, and that the shape of their antlers signified a particular time of year.

This level of insight suggests that early humans were developing a deeper connection with their environment. They were not merely surviving within it, rather, they were understanding it, learning its patterns, and incorporating that knowledge into their artistic expressions.

The Swimming Reindeer is more than a work of beauty; it is an artifact of human intelligence, a record of early ecological awareness.

From depiction to understanding

Both the Bison Licking Its Back and the Swimming Reindeer mark a turning point in artistic evolution. These were no longer simple images of animals but representations of animals as they lived, moving, interacting, and existing within the greater cycles of nature.

This shift in artistic expression parallels the cognitive evolution of early humans. As their understanding of the natural world grew, so did their ability to translate that knowledge into their creations.

Art became a means not just to depict, but to communicate, to share wisdom, to teach, and perhaps even to preserve memories of seasonal rhythms and animal behaviors crucial for survival.

In many ways, these ancient sculptures foreshadow the way art would develop in later civilizations.

From the lifelike animal frescos in Egyptian tombs to the detailed wildlife sketches of Renaissance masters, the impulse to observe and record the natural world remains a constant thread throughout human history.

Art as an act of connection

What strikes me most about these pieces is the intimacy of their creation.

The artist who shaped the bison, pressing their fingers into soft clay, knew that animal well, its movements, its habits, and the way it carried itself.

The one who carved the reindeer, painstakingly chiseling the contours of their bodies into ivory, must have watched these creatures in the wild, understood their migration patterns, and internalized the subtle relationships between them.

This is what makes early art so powerful. It is not just about what was created but about the relationship between the artist and the subject.

In these pieces, we see the emergence of something profound: the realization that art is not merely about representation but about connection. It is about understanding, about seeing the world not as separate from us, but as something we are inherently a part of.

Thousands of years later, as I reflect on these sculptures, I find myself asking the same questions those early artists might have pondered.

What do I see when I look at the world around me?

How do I translate what I observe into my own art?

And most importantly, how can we, as artists, continue the legacy of observation, curiosity, and connection that began so long ago?

In the end, the Bison Licking Its Back and the Swimming Reindeer are more than just artifacts—they are echoes of an ancient way of seeing. And through them, we are reminded that art, at its core, is not just about capturing what we see. It is about truly understanding it.