A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

(Shakespeare)

Language is our species' greatest achievement. It is the foundation for all following technological advancements. It is also, for Rutherford Medal prize winner Michal Corballis, the “hardest problem in science”: no one completely understands how it works and where it comes from.

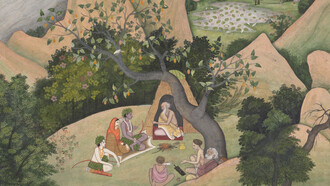

In the fifth century BCE, a scholar from India named Panini documented the rules of Sanskrit grammar, marking the beginning of a field of study that is now known as linguistics. Facets of linguistics include language acquisition, use, structure, and history.

The field of study has six main branches: phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, syntax, and pragmatics. Subbranches also appeared, including phonosemantics. I talked to Paweł, a linguist who has worked with phonosemantics for two decades. He advances that most of the 6000 languages in the world have common roots.

Paweł does not fully agree with the widely accepted theory that many words were simply invented and that we will never know how or why. For him, phonosemantics played a significant role in the creation of languages.

“Many linguistic journals said that they won't publish anything about the origin of language because they argue it is complete speculation,” told me Paweł. “For me, this [the origin of words] is the main topic because I'm dealing with the theory of phonosemantics.”

“In this theory, language starts with concrete, physical meanings and the quality of the sound you hear,” he explains. “It’s not a mainstream theory,” he adds. “It has followers, of course, all over the world, but very few.”

He gives me examples: something that is brutal, abrupt is more susceptible to producing sounds like “kh.” Why do you call a crow a crow? “Because it caws.” Another onomatopoeia: “What does the cat do? He meows, because it’s the sounds he makes.”

Paweł says that these are simple cases, but many cases are not as obvious.

“Take the word ‘hit.’ It is a very short word, pronounced quickly, with a short vowel inside, and ends with a full stop, creating a short sound. You make it with the teeth. Related words, such as striking and beating, almost always end with a stop consonant.”

In his theory, language starts with those concrete, physical meanings. All these meanings, in his theory, came from your internal perception of the quality of sounds and with the place of articulation. The sounds “mmm,” which babies use, can be said with your mouth shut. It symbolizes what is internal. The second mantra, mostly in India, is Om̐: the original sound from which the universe was created, which symbolizes descending into what is more internal: the sounds made by “what you have inside, with your mouth shut,” he said. We find it in “Me, maman, mum, mamá, amma, 妈妈 (māma)…”

He made numerous similar observations.

“If you learn many languages that are connected to each other, there are so many variations of the same word that have the same meaning. But if you have all of it in your short-term memory, then you begin to identify patterns. The human brain is made for it.”

He adds that different extensions tend to have slightly different meanings, which are very easy to explain.

Phonosemantics started in the 18th century with Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov. In his peculiar theory, words with vowel sounds made in the front of the palate should be used to portray delicate subjects, and more guttural sounds, made with the back of the palate, should be used to describe more negative things.

The theory was widely discussed in the 19th century, with the development of the comparative method in the academic world: a set of guidelines that allow languages to be compared to one another in terms of vocabulary, grammatical structures, and sound, in an attempt to demonstrate their common roots.

However, Ferdinand de Saussure, in the late 19th century, advanced an opposite theory: that sounds are arbitrary, and words are chosen by consensus.

The connection between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary.

(Ferdinand de Saussure)

We will remember here the line from Romeo and Juliet: “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” De Saussure believed that the interpreter could only determine the meaning of the language by examining the network of signals and their negations. “That was called the fundamental theory of linguistics,” told me Paweł, reiterating that after a long period of work, he understood that, according to him, the theory was wrong.

A few decades after de Saussure’s theory, in 1929, in a series of psychological tests on the Spanish island of Tenerife, German-American psychologist Wolfgang Köhler asked participants to identify two shapes, a spiky and a round one: one as a "takete" and the other as a "baluba" (which he changed to "maluma" in 1947). Most participants associate “takete” with the spiky shape and “maluma” with the round one. Using the terms "kiki" and "bouba," linguists Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard replicated Köhler's experiment in 2001 and had the same results.

Are the sounds we use related to other perceptions we have?

This is a part of what we call the theory of multi-sensory processing: some sounds would go better with some visual information or sensory associations than others.

Suzy Styles, assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, in an interview on the podcast “Lingthusiasm,” gives the example of a staple and a stapler falling on a hard table and asks the listeners to imagine the type of sound each would make. According to her, the acoustic features of the staple would be high-frequency, high-pitched elements, quiet and short-lasting, while the acoustic features of the stapler would be lower-pitched, louder, and longer-lasting.

“What we’ve got already is that for objects in the world that are small, the sounds that go along with them are going to be high frequency, quiet, and short-lasting,” she explained to the listeners.

This brings us back to the takete-maluma theory: a near-universal phenomenon, highly replicable.

If languages can bring us together, they can separate us. Corballis has a theory: “I think it’s because we partly design language to keep other people out, so that people won’t understand us. Language is not only a means of communicating; it’s a means of preventing communication, a kind of fortress that we build around us.”

The complexity and allure of language remain an ever-fascinating subject, continually revealing its mysteries and intricacies.